15 Energy Associated with Motion at the Molecular Scale – Temperature

Brokk Toggerson

While we already know from our unit on entropy that temperature is the average energy per degree of freedom, ![]() . However, we should probably expand on this idea a bit more to properly define what degrees of freedom are available to different materials and the units of temperature.

. However, we should probably expand on this idea a bit more to properly define what degrees of freedom are available to different materials and the units of temperature.

Degrees of Freedom in Materials

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to…

- Recall and list the number of degrees of freedom in a ideal monatomic gas.

- Predict the number of degrees of freedom for an ideal gas which is constrained.

- Recall and list the number of degrees of freedom for an Einstein solid.

- Predict the number of degrees of freedom for an Einstein solid of dimension lower than 3.

- Recall and list the number of degrees of freedom in a ideal diatomic gas.

- Describe how the number of degrees of freedom for an ideal diatomic gas changes with temperature.

In the chapter on The Basics of Matter, we saw two molecular attributes: its motion and any bonds around it. Molecules in gases or liquids have yet a third attribute: the molecule as a whole can rotate (spin). Each of these attributes is a place where I can put some energy (a degree of freedom). Thus, different molecules will embody temperature differently.

Monatomic Ideal Gases and Other Systems Where the Particles are Free to Move About

The simplest substance is the . These spheres can only move in three : up/down, left/right, and front/back. Thus, if I add energy to an ideal gas molecule, or other particle which is free to move about, then there are three places I can put that energy, I can:

- Increase the speed in the front/back direction.

- Increase the speed in the left/right direction.

- Increase the speed in the up/down direction.

Thus any particle free to move in all three directions has three degrees of freedom. If the motion is constrained in some way, then there may be fewer!

Example: Electrons in Chlorophyll-a

Problem:

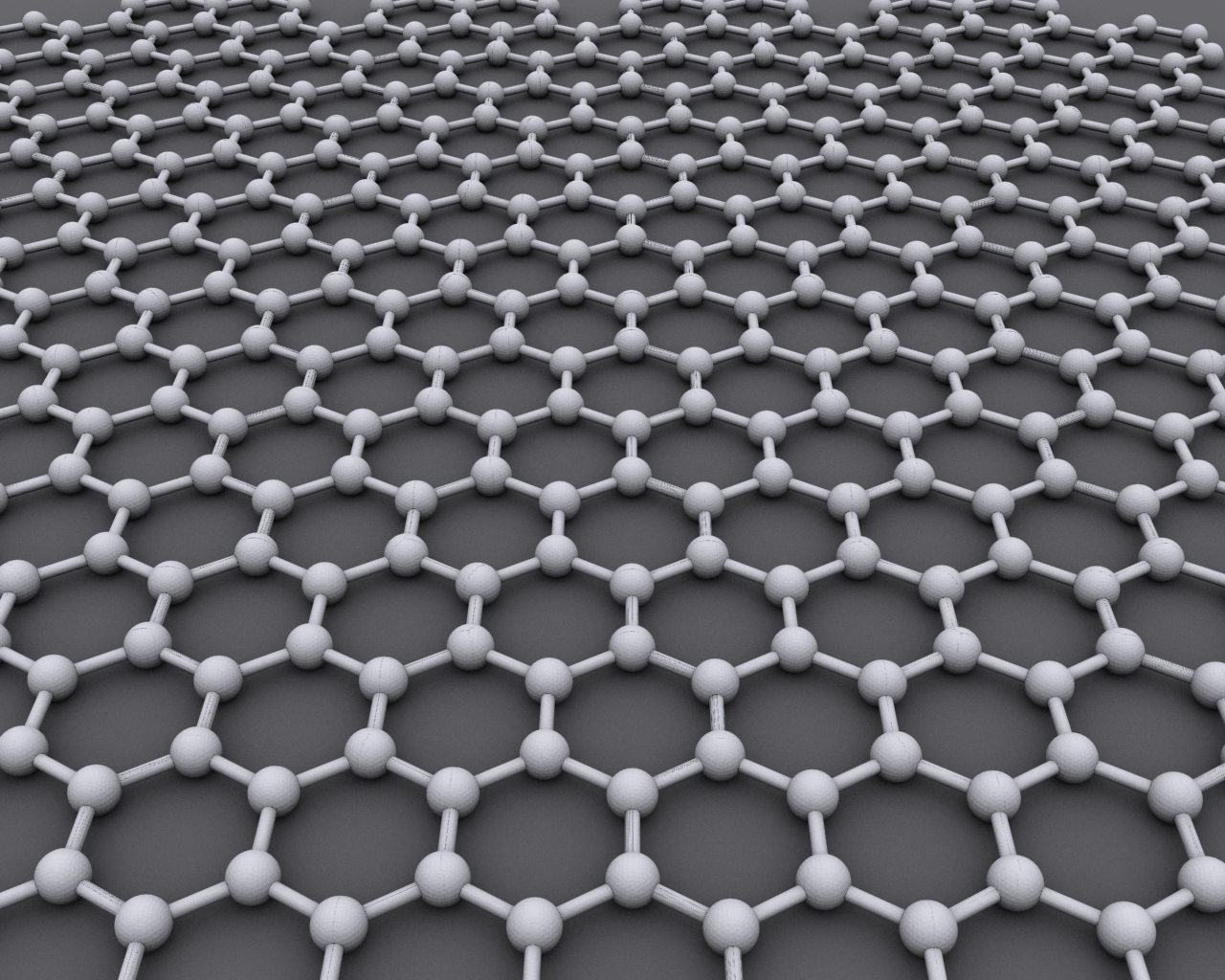

Graphene is an exciting form of carbon first isolated in 2004 and comprises a single sheet of carbon atoms. The material is a conductor of electricity meaning that electrons are free to move about the sheet.

How many degrees of freedom would such electrons possess?

Solution:

These electrons would have two degrees of freedom: front/back and left/right. They are not allowed to leave the sheet so the up/down degree of freedom (perpendicular to the sheet) is cut off for them.

Key Takeaways

- Atoms or molecules get one degree of freedom for each direction in which they can move; if they can move in all directions, that is three degrees of freedom:

- Up/Down

- Left/Right

- Front/Back

- Sometimes, specific degrees of freedom are suppressed due to various parameters which prevent motion in specific directions and thereby reducing the degrees of freedom.

Degrees of Freedom in Molecular Bonds

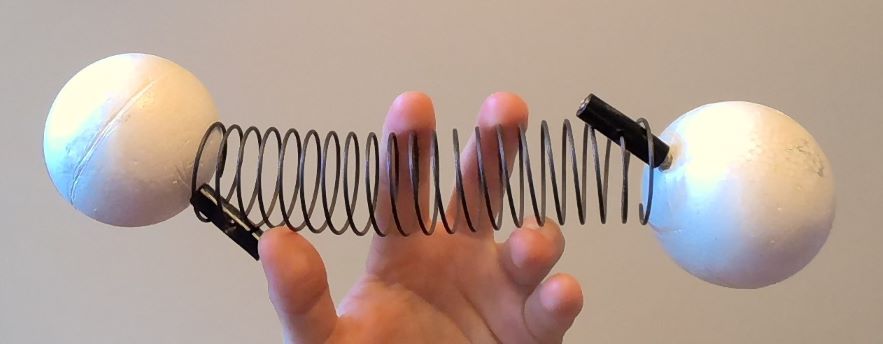

As we saw in the chapter on Overview of the Types of Energy, chemical bonds can be well modeled as springs. As we will see in our last unit, each spring has two degrees of freedom: I can increase the size of the oscillations and the speed of the oscillations separately. This means that each bond has two degrees of freedom: one for the size of oscillation and one for the speed of oscillation.

Example: Solids

Problem:

As we saw in the Basics of Matter, each atom in a solid can be thought of as connected by three pairs of springs, the so-called Einsteinian solid.

How many degrees of freedom would such a solid possess?

Solution:

There would be 6 degrees of freedom: one for the “springs” in each direction: left/right, up/down, and front/back. We do not count the left and right springs separately as they are not independent: if the left spring gets longer, the right spring gets shorter by the same amount and at the same speed.

Example: Diatomic Molecules – Motion and Bonds

Problem:

Consider a molecule of a diatomic gas such as O2. The molecule is free to move about the room, but there is also a bond which can vibrate.

How many degrees of freedom does this molecule possess if I consider both of these types of motion?

Solution:

There are five in total:

- Three associated with the motion of the molecule around the room:

- Left/right

-

- Up/down

-

- Front/back

- Two associated with the vibration of the bond – one spring with two degrees of freedom:

- Size of oscillation

-

- Speed of oscillation

Key Takeaways

- Bonds can be modeled as springs.

- Each bond/spring gives two degrees of freedom:

- One for the speed of the oscillation.

- One for the size.

Rotational Degrees of Freedom

Key Takeaways

In addition to degrees of freedom associated with the motion of the molecule as a whole (translational) and those associated with bonds (vibrational), there are also degrees of freedom associated with rotation (rotational).

- These are only available in gases and liquids where the molecules are free to move about.

- There is one degree of freedom for each axis where the molecule has some size.

- Spinning monatomic molecules does not count as they (according to our ideal gas model) do not have size.

- Similarly, spinning diatomic molecules the “long way” does not count as the molecule has no size about that axis.

Degrees of Freedom as a Function of Temperature

How Different Materials’ Different Degrees of Freedom Impact Their Distribution of the Kinetic Energy Associated with Temperature

As we have seen, different materials have different numbers of degrees of freedom:

- Monatomic ideal gases have three degrees of freedom associated with translational motion up/down, left/right, and front/back.

- Solids have six degrees of freedom: two associated with each bond/spring.

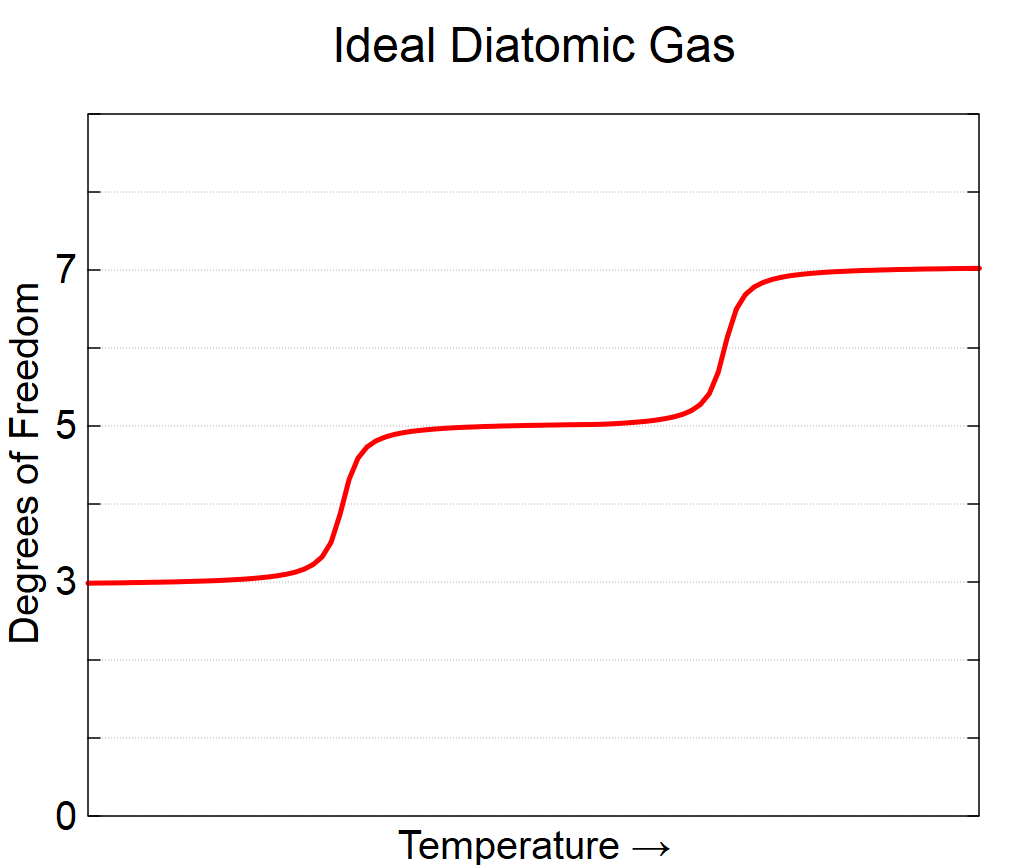

- Diatomic ideal gases have a number of degrees of freedom which depends on temperature: the three translational motion are always available, the two rotational ones (giving a total of five) are available at intermediate/room temperatures, and at high temperatures, I can get the two degrees of freedom associated with vibration for a total of 7.

These different numbers of degrees of freedom impact how different materials distribute the kinetic energy associated with temperature. As we saw in the in our Entropy Unit, energy tends to be distributed equally among all the different degrees of freedom. Since temperature is the average kinetic energy per degree of freedom, ![]() , if two materials have the same temperature, then the one with more degrees of freedom will have a higher average energy.

, if two materials have the same temperature, then the one with more degrees of freedom will have a higher average energy.

![]()

![]()

.

Examples: Comparing the Average Energy of Molecules in Different Substances

Problem:

Consider solid gold, helium gas, and diatomic nitrogen gas N2 all at room temperature. Which atoms have the highest average energy?

Solution:

The gold, being a solid, has 6 degrees of freedom, while helium as a monatomic gas has three. Nitrogen is a bit more complex, but, as seen above, has 5 degrees of freedom at room temperature (3 translation and 2 rotation). Thus,

- The gold atoms have the highest average energy.

- The nitrogen molecules are next.

- The helium atoms have the lowest average energy.

Temperature Scales and Reference Points

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to…

- Define absolute zero.

- State the Third Law of Thermodynamics.

- Describe the basis of the Kelvin scale of temperature.

- Convert between Celsius and Kelvin.

- List the Celsius and Kelvin temperatures for a few reference points.

Just as with the other quantities we have explored (force, energy, and mass), it is useful to understand the units of temperature and have memorized a few reference points.

The Kelvin Scale and Absolute Zero

As we have seen above, temperature is defined as the average energy per degree of freedom. What if that average energy were zero? This would provide an absolute minimum temperature. This minimum temperature, , is defined as the zero of the so-called , ![]() (note the lack of a degree symbol, its

(note the lack of a degree symbol, its ![]() NOT

NOT ![]() !). The Kelvin scale then proceeds from the absolute zero in steps the same as a degree Celsius (

!). The Kelvin scale then proceeds from the absolute zero in steps the same as a degree Celsius (![]() ). In other words if two temperatures are

). In other words if two temperatures are ![]() apart, they are also

apart, they are also ![]() apart.

apart.

Example: Counting Kelvins

Problem:

You probably know that the freezing point and boiling points of water are ![]() apart: the freezing point of water is defined as

apart: the freezing point of water is defined as ![]() and the boiling point is

and the boiling point is ![]() . How many Kelvin apart are these two temperatures?

. How many Kelvin apart are these two temperatures?

Solution:

Since the size of Kelvin steps are the same as the size of Celsius steps, then the freezing and boiling points of water are ![]() apart.

apart.

Counting in ![]() steps from absolute zero, we find that the freezing point of water (defined to be

steps from absolute zero, we find that the freezing point of water (defined to be ![]() ) will be

) will be ![]() . This means that the conversion between Kelvin and the more familiar Celsius is simple:

. This means that the conversion between Kelvin and the more familiar Celsius is simple:

![]()

Example: The Boiling Point of Water

Problem:

What is the boiling point of water in Kelvin?

Solution:

Using the conversion factor above, and knowing that the boiling point of water is ![]() , we see that

, we see that

![]()

![]()

![]()

Is Absolute Zero Possible?

The short answer is: no. Due to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle[1] (which you may have studied in Chemistry), it is impossible for atoms to cease moving[2]. As such, absolute zero is impossible, a fact known as the . We have, however, gotten quite close: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lowest_temperature_recorded_on_Earth#Modern_experiments.

Reference Points for Temperature

As before, we expect you to have these reference points memorized. If only one temperature is given for a given condition, you only need to memorize the one. If you were not raised in the United States, then you probably already know the Celsius values! In many cases the conversions between Celsius and Kelvin (and, when appropriate Fahrenheit) in this table are approximate to make them easier to remember (which is the whole point of reference points). Look for ~ to indicate approximate conversions.

| Conditions | Celsius Temperature | Kelvin Temperature |

| Deep outer space | – | 2.7 |

| Liquid Nitrogen | – | 77 |

| Really cold day in Amherst, MA ( |

-25 | – |

| Average January day low in Amherst, MA ( |

-10 | – |

| Freezing point of water | 0 | ~273 (technically 273.15) |

| Average March day high in Amherst, MA ( |

7 | – |

| Average October day high in Amherst, MA ( |

18 | – |

| Room Temperature ( |

~20 | ~293 |

| Body Temperature | 37 | ~310 |

| Really hot day in Amherst, MA ( |

40 | 313 |

| Boiling point of water | 100 | ~373 (technically 373.15) |

Homework

- Degrees of freedom.

- Degrees of freedom in an electron transfer.

- Energy at a given temperature.

- Reference points for temperature in Celsius and Kelvin.

- Conversion from Celsius to Kelvin.

- It is impossible to know the position and speed of a small object at the same time with perfect precision. ↵

- If they did, we would know their speed exactly and would therefore have no information at all with regards to their position. In effect the atoms would be everywhere in the universe at once! ↵

An idealized model of a gas. In this model, the molecules of the gas are visualized as spheres with mass, but zero size. Having zero size implies that these molecules cannot collide with one another, but only with the walls of their container. Thus, the molecules travel in straight lines until they hit the wall from which they bounce without a loss of energy.

A possible direction of motion. Our world generally has three spatial dimensions: up/down, left/right, and front/back though lower dimensional systems can exist by constraining motion in specific directions only.

All microstates in a given macrostate are equally likely.

The coldest possible temperature at which the average energy per degree of freedom is zero. Turns out this is actually impossible due to quantum mechanical effects, a fact stated as the Third Law of Thermodynamics.

A temperature scale which starts at absolute zero and has steps the same as a degree Celsius.

Absolute zero is impossible.