11 Learning Together: Four Institutions’ Collective Approach to Building Sustained Inclusive Excellence Programs in STEM

Jeremy Wojdak, Tara Phelps-Durr, Laura Gough, Trudymae Atuobi, Cynthia DeBoy, Patrice Moss, Jill Sible, and Najla Mouchrek

1 Introduction

Inclusive excellence as a concept in higher education unifies aspirations for equitable student success and shifts in institutional culture and practices to better value representational diversity (Clayton-Pederson et al., 2017). Here, Radford University, Towson University, Trinity Washington University, and Virginia Tech, each awarded 2017 Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Inclusive Excellence (IE) grants, report on efforts to create inclusive student programs in STEM. Midway through the five-year grant, two themes have emerged: 1) faculty play an essential role as change agents in inclusive excellence and must be empowered to lead and be credited for this work, and 2) convening diverse institutions in learning communities provides peer support and facilitates progress toward inclusion.

2 The Howard Hughes Medical Institute IE Program

Despite major investments supporting equitable outcomes for students who have been underrepresented in STEM (e.g. students of color, first-generation college students, and transfer students), progress has been limited (President’s Council of Advisors for Science and Technology, 2012). Even when initiatives such as summer bridge or tutoring programs yield success for individual students, institutions often remain fundamentally unchanged when funding for these programs ends.

HHMI sought a different approach to create sustained advances toward inclusion: “All students, regardless of where they come from and where they are going, deserve a meaningful and positive experience in science through which they will better understand and engage in scientific thinking and discovery. The quality of that experience is the responsibility of the faculty and administrators who play an essential role in defining an institution’s culture.

Unfortunately, there exist substantial disparities between students who arrive at college via different pathways. Students who are first in their families to attend college, students who transfer from 2-year to 4-year schools, and students from racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups underrepresented in science are significantly less likely to complete the baccalaureate degree” (HHMI, n.d.).

In response to this challenge, HHMI launched the Inclusive Excellence program to change the institution, not fix the student, encouraging grantees to reject a deficit mindset regarding students and turn a critical eye toward how institutions themselves needed to change. At the 2017 kick-off meeting, HHMI provided grantee institutions with a sense of mission, some theoretical grounding, and frameworks regarding inclusion and institutional change. However, the approach to inclusive excellence was not prescribed, and institutions were encouraged to “experiment” as they applied their learning to institution-specific goals and contexts. To support this work, HHMI built a network of regional communities of practice, called Peer Implementation Clusters (PICs) and engaged project leadership in professional learning, mentoring, and reflection. Like described in the work of Finkelstein et al. (this volume), this model values cross-institutional research and collaboration, creating a process of collective emerging learning. To date, HHMI has awarded $1M each to 57 institutions over two rounds of funding.

3 Institutional Profiles and Project Overviews

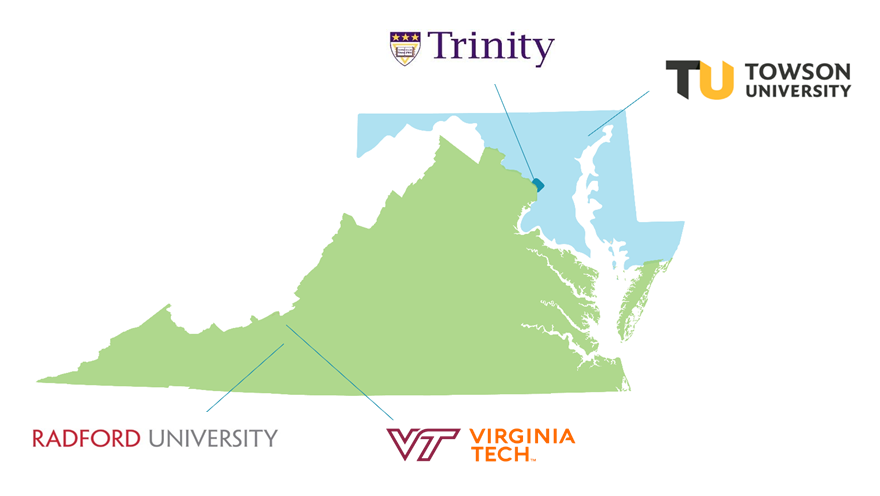

We constitute the South PIC institutions among the 2017 HHMI Inclusive Excellence awardees (Figure 1). As we approach midway in the five-year grant period, we reflect upon progress and challenges that must be overcome to emerge as more inclusive institutions. Our South PIC is representative of the diversity of institutions that are part of the HHMI program (Table 1). Collectively, our institutions are public and private faith-based; small, medium, and large; predominantly black and predominantly white; rural and urban.

| Institution | Radford University | Towson University | Trinity Washington University | Virginia Tech |

| Location | Radford, VA | Baltimore, MD | Washington, DC | Blacksburg, VA |

| Undergraduate Enrollment (Fall 2019) |

7,967 | 19,800 | 1,500 | 29,300 |

| Institute Type | Four-year, medium, public, primarily residential | Four-year, large, public, primarily residential | Four-year, small, faith-based, primarily nonresidential |

Four-year, large, public, primarily residential

|

| Carnegie Classification* | Master’s Colleges and Universities: Larger Programs | Doctoral/Professional Universities | Master’s Colleges & Universities: Medium Programs |

Doctoral University; Very High Research

|

| Student Demographics** | 34% ethnic minority; 60% female; 32% first-gen | 45% non-white; 50% transfer; 60% female | 90% African American and Latina; 100% female (in Arts and Sciences) |

9% underrepresented minority; 9.5% transfer; 16% first-gen

|

| Students Receiving Need -Based Aid*** | 64% | 55% | 100% | 39% |

*The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education (n.d.).

**Rather than adopt common language, we present the demographic categories as used by each institution, reflecting differences in institutional culture and practice.

***US News and World Reports for Radford, Towson, VT; Trinity self-reported.

Here, we share an overview of the inclusive excellence activities implemented by our respective universities, highlighting the commonalities that have emerged (Table 2).

Note: PBL: problem-based learning; IE: inclusive excellence; FYE: first-year experience; CURE: course-based undergraduate research experience.

| Institution | Radford University | Towson University | Trinity Washington University | Virginia Tech |

| Participating units | Biology, Chemistry, and Physics | Biology, then expanded to Chemistry and Mathematics | Biology, then expanded to Mathematics |

Fish and Wildlife, Human Nutrition Food and Exercise, Neuroscience, Chemistry, Biochemistry, Geosciences, Animal and Poultry Science, and Forest Resources & Environmental Conservation

|

| Faculty learning | Faculty trained in PBL and inclusive pedagogy | Faculty meet monthly for a year to learn to teach CUREs and inclusive teaching practices | Faculty learning on understanding bias, culturally competent teaching, increasing student engagement, becoming effective mentors |

Faculty cohorts spent a year learning through fall workshops, spring reading groups, a summer institute; departments have additional faculty learning contextualized for their programs.

|

| Faculty incentives | Faculty grants and release time |

Faculty stipends and release time

|

Faculty named scholars; summer salary, IE faculty award

|

|

| Curricular reform | Faculty implement PBL in their classes | Faculty creating and teaching CUREs; students take CUREs as part of degree | Built flexibility into course sequencing for biology and chemistry; relaxed prerequisites |

Varies by department: e.g offering key courses both semesters, piloting PBL-based learning; embedding research in curriculum

|

| Mentoring and student support | Peer mentors host social and academic events | Mentoring and other student supports embedded into class time | Developed Mentor Moments, 1-credit courses at each academic level |

Varies by department: e.g. expanding FYE course to second semester to provide additional mentoring; partnering with Student Affairs to support students in recovery

|

| Expanding the network | Teaching postdocs play a critical role |

High school teachers engaged in professional learning

|

Undergraduate fellows initiate their own IE projects

|

3.1 Radford University

At Radford, we launched the Realizing Inclusive Science Excellence (REALISE) initiative to create a welcoming, inclusive learning environment for all students. The cornerstone of our approach is providing professional learning within a community for faculty to embed project-based learning and inclusive pedagogy into curricula. 21 faculty have participated in REALISE, representing 33%, 62%, and 63% faculty participation in the departments of Biology, Chemistry, and Physics, respectively. Upon completing their professional learning, participants receive one semester half-time reassignment to implement their course redesign, providing the rate-limiting resource for faculty: time. Like the BioTAP initiative described by Gardner et al. (this volume), to seek sustained change through work with future faculty, REALISE engages postdoctoral teaching fellows as essential members of these learning communities. These fellows contribute to curricular reform while developing their own skills to transition into permanent positions as change agents in higher education. REALISE student leaders build community by hosting social (tie-dye, student/faculty mixers, movie nights, fresh fruit Fridays) and academic (CV writing workshops, career exploration day) events. Participation in these activities has steadily increased over the past three semesters, and surveys demonstrate that our students desire more.

3.2 Towson University

At TU, student persistence and retention are lower for transfer students, who comprise half of our student body. With HHMI funding, we created the TU Research Enhancement Program grounded in the creation of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs) to engage more students in authentic research (Auchincloss et al., 2014; Oufiero, 2019), which can increase retention of all students in science, including those from underrepresented groups (e.g., Shaffer et al., 2010; Bangera & Brownell, 2017). In the revised curriculum, students take CUREs in subjects including genetics, cell biology, field ecology, and forensics. As at Radford, professional learning for faculty is the key to our curricular change project. Faculty cohorts of six to eight members engage in monthly professional learning activities for one year to develop their CURE and learn inclusive teaching techniques. These activities have further created additional connections among STEM faculty and diversity and inclusion staff in the Office of the Provost and President. In addition, we have explored student needs and worked to enhance and connect across existing university resources to ensure students can utilize academic and social supports. We are beginning to offer additional supports during classroom time (e.g., mini-discussions or presentations about internships, graduate school, and study skills) to reach thousands of students who are not able to attend activities outside of class. We co-developed a summer workshop for high school teachers modeled on our Molecular Biology Lab CURE. This workshop includes a forum for TU faculty to discuss inclusion and research-based instruction with these teachers. We learn about the challenges they and their students face, and the high school teachers explore implementing authentic research activities in their own classrooms.

3.3 Trinity Washington University

Trinity Washington aims to increase the number of women majoring in the sciences. More than 90% of Trinity’s students in the College of Arts and Sciences are African American and Latina. While 94% of science majors taking introductory chemistry in 2013 had graduated by 2018, only 44% graduated as science majors. In response, Trinity faculty developed Trinity ExCEL (Excellence x Confidence Equals Leadership). Similar to TU, we recognized that our students faced extensive commitments outside of school, and thus, initiatives must be embedded within the curriculum. Our program is grounded in faculty professional learning selected from topics that faculty requested: 1) understanding the impact of our own biases, 2) developing strategies for culturally competent teaching, 3) increasing student engagement, and 4) becoming more effective mentors. With such training, we support faculty to promote asset-based learning through student empowerment, and foster student-instructor interactions, thereby creating a framework shown by Lee et al. (2019) to be an effective model to improve minoritized student learning outcomes in STEM. We used training to inform our curriculum redesign, which included relaxing prerequisites and the prescribed order of courses to increase flexibility for students who may otherwise fall off-cycle. We also included 1-credit mentoring courses to help students become self-regulated learners as described by Sebesta et al. (2017). Mentor courses increase faculty and peer mentorship and focus on: 1) student belonging and self-efficacy, 2) communication in academia, 3) obtaining experiential learning, and 4) post-baccalaureate careers. Furthermore, pillars shown to support student success including mentorship, student mindset, and student learning techniques (Lisberg & Woods, 2018) have been incorporated into our revised curriculum.

3.4 Virginia Tech

At Virginia Tech, our Inclusive Excellence project engages multiple science departments, supported by university-level administration, as a strategy for sustainable change at a large, decentralized institution. While our retention (>90% first-to-second year) and graduation (>85% 6-year graduation) rates are high for students in our science programs, disaggregated data revealed disparities for students from identities that are marginalized in STEM (underrepresented minorities, transfer, and first generation). Moreover, students from these identities reported that the Virginia Tech tagline, “This is home,” did not apply for them. Each year, faculty members are recruited from up to three departments to participate in a year of professional learning in inclusive pedagogy. They learn theoretical foundations (e.g., stereotype threat, implicit bias), and based on faculty request, also learn practical and discipline-specific approaches to improve their teaching and mentoring. Faculty participate in guided reflection about their learning. As in the work described by MarbachAd et al. (this volume), participating departments consider disaggregated data and focus group reports for their own students to reveal disparities for marginalized populations. Like MarbachAd et al., we recognized the quite different contexts across departments and predicted a one-size-fits-all approach would not work for building sustained change. Thus, we distribute the majority of our Inclusive Excellence funding as mini-grants, giving departments agency to implement projects of their own design. These projects emerge from ideas that department faculty develop collaboratively and are contextualized to each department’s needs and culture. To date, eight departments and 45 faculty from three science colleges have been involved.

4 Emergent Theme: The Critical Role of Faculty in Building Inclusive Excellence

As the reports from our institutions demonstrate, our various “experiments” share common themes (Table 2), the most central of which is faculty learning and subsequent expectations for faculty to implement pedagogical and curricular reforms that promote inclusion. This work is challenging logistically, intellectually, and emotionally, and frequently, is in addition to a full faculty workload. Across the South PIC, faculty are willing to commit to this work for extended periods of time. While professional learning has taken many forms (workshops, summer institutes, guest speakers, reading groups), a common theme has been faculty communities that meet regularly for months to years and engage in reflection, a practice recognized to promote sustained changes in STEM teaching (Henderson et al., 2011). Peer support has been critical within our institutions to help faculty remain engaged in these projects and develop changes in mindset and habits. Faculty who started as participants now serve as leaders among their peers, presenting at departmental and South PIC meetings. While each of our inclusive excellence teams contains administrative leadership, these administrators serve primarily in advocacy and support roles, recognizing faculty as the primary change agents.

The content for faculty learning has largely fallen into two categories: 1) learning about diversity and inclusion (e.g. implicit bias, stereotype threat), and 2) pedagogical training. The former has been led by national and campus experts. The latter has frequently fallen into the “good pedagogy” category based on the prediction that more learner-centered approaches will reduce achievement gaps for the populations of students that are the focus of this project, as supported by a number of studies (e.g. Beichner et al., 2007; Eddy & Hogan, 2014). However, in some fields, these pedagogical approaches have exacerbated achievement gaps (e.g., Johnson et al., 2019; Setren et al., 2019), highlighting the importance of a more comprehensive approach to professional learning. Beyond more generalized training in “active learning” approaches, much of our faculty learning has been focused directly on inclusive pedagogy (e.g., writing inclusive syllabi, adopting inclusive language) to apply lessons learned from the diversity and inclusion awareness training. One important question that will be addressed by our Inclusive Excellence projects is whether the pairing of faculty learning in diversity and inclusion with pedagogical training provides an effective strategy for reducing success gaps in our classrooms. Other important aspects, echoing the work of Margherio et al. (this volume), are the creation of strategic partnerships leading to shared vision and mutual learning.

As we consider what it will take to sustain our work beyond the lifetime of the grants, we must consider the essential role that we have defined for faculty who must make difficult decisions about how to spend their time in ways that align with institutional priorities. We appreciate the empathy and respect for faculty put forth by The Every Learner Everywhere project in the New Learning Compact, and have adopted their stance and some of their language (e.g., “professional learning” instead of “faculty development”) in our inclusive excellence work (Bass et al., 2019). Given that few arrive at faculty positions with expertise in pedagogy or inclusion, faculty learning must be recognized as part of faculty workload (Neumann, 2005). Our faculty stress that time needs to be devoted to course development and redesign, practice, reflection, and peer support. The particular situations may differ among faculty, ranging from part-time instructors who should be paid for time spent on professional learning, to assistant professors with high expectations for research accomplishments to earn tenure. However, the take-home message is consistent: if inclusive excellence initiatives are to expand beyond the early adopters and be sustained beyond the lifetime of a grant, the work must be recognized and rewarded, including counting towards tenure and promotion. Otherwise, our work risks contributing to workload disparity issues that tend to negatively impact women and faculty of color (O’Meara et al., 2018). While we share our success to date, collectively we have seen participation in some of our more time-consuming faculty learning initiatives begin to decline. Reflecting on our work in the context of the systems approach to change described by Kezar and Miller (this volume), we find that our institutions have made good progress in providing the pedagogical tools and infrastructure to advance inclusive excellence, but risk failing at long-term cultural change if we cannot impact changes in policy regarding faculty recognition and rewards for this work.

5 Learning Together: The Value of our Peer Implementation Cluster

The organization of Inclusive Excellence grantees into PICs was one strategy HHMI employed to facilitate sharing and learning across the grantee institutions. The clusters were organized geographically so that institutions could convene at least once a year. The South PIC typifies the diversity of these clusters (Table 1). Institutional leaders from each PIC were first introduced to each other by HHMI during the kickoff meeting in the summer of 2017. During this introduction, we shared our initial challenges, goals, and strategies. Despite differences not only among our institutional profiles but also in our planned approaches to inclusive excellence, we recognized the potential to learn from each other.

The nature of South PIC interactions has evolved substantially over the past two and a half years. In the first year, each institution was focused on launching its own program, and the PIC meetings were limited to formal monthly virtual meetings to plan a spring 2018 South PIC gathering to be hosted by Trinity Washington University. This event, held in May 2018, brought together ~35 individuals across the four institutions for two days of professional learning led by national experts, HHMI, and Trinity Washington faculty. During year 1, Radford and Virginia Tech, co-located in rural Southwest Virginia, extended reciprocal invitations to share professional learning events including visits by national and local experts from each institution. Towson and Trinity Washington shared strategies for assessment and facilitating student mentorship. Additionally, Towson’s Vice President of Inclusion and Institutional Equity and Coordinator of Diversity Training facilitated professional learning for Trinity faculty. An Inclusive Pedagogy Faculty Mentoring Network (sponsored by the QUBES: Quantitative Undergraduate Biology Education and Synthesis project) with participation from all four institutions met every other week in the fall of 2018 to discuss readings on a range of topics. In April of 2019, faculty from each institution partnered to offer a workshop on inclusive excellence as part of the ASCN Transforming Institutions Conference, providing the basis for this collaborative report. The South PIC convened at Virginia Tech in June 2019 for its annual meeting, which was combined with Virginia Tech’s two-day Summer Institute professional learning event for over 200 faculty. Towson hosted a virtual South PIC meeting in May 2020 with a focus on the impact of COVID-19 on the work of inclusive excellence. 70 colleagues from the South PIC institutions as well as Bowie State, Community College of Baltimore County, and Baltimore City Community College attended.

Beyond these formal interactions, the South PIC has become a community of support, particularly for program leaders as we strive to institutionalize projects at our respective universities. As many of our participating faculty have begun attending conferences focused on inclusion in STEM and professional learning, we seek out one another at national meetings and invite each other to give presentations at organized symposia. South PIC program directors chat regularly to share mentorship in matters ranging from how to approach the reflection-based annual reports to how to best support faculty who are overwhelmed during the COVID-19 crisis. We have helped one another identify program evaluators and workshop facilitators. We have pointed to examples of strong support from university leadership at one another’s institutions as we seek to influence change at our own. This building of professional relationships of mutual support and trust has developed organically without a formal, common framework as described by Finkelstein et al. (this volume) for their teaching evaluation project. In contrast to the AAU STEM network (Kezar & Miller, this volume) and other STEM change initiatives, the Inclusive Excellence PICs do not bring together like institutions. The groupings based solely on geography provide an element of the larger experiment that HHMI has undertaken, and we recognize the foresight of HHMI that modeled the principles of inclusive excellence by bringing together institutions with diverse profiles to learn together toward a common goal. Our annual PIC meetings provide us with an opportunity to introduce more faculty from each institution to inclusive excellence work and to the group, developing additional networking opportunities across campuses.

6 Institutionalizing Inclusive Excellence

Each of our programs has reported progress toward sustaining their inclusive excellence programs. Science departments beyond those involved when the grants were awarded have joined our projects. We have partnered with university-level administration to expand professional learning programs in diversity, equity, and inclusion to campus-wide initiatives. Presidents, provosts, and in some cases, Boards of Visitors/Trustees have been present to learn and then advocate for our projects on all four campuses. Our faculty have become involved in student-life issues ranging from food insecurity to substance use disorders. Perhaps the most visible result of this work in Spring 2020 has been how participating departments have responded to the sudden move to on-line teaching and learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Faculty who had been engaged in professional learning about issues of equity and inclusion have approached on-line learning through these lenses. They considered access to learning for all students, participating in webinars and discussions with colleagues to consider these issues. The flexibility required to learn how to teach inclusively has been an asset for us as we navigated this new environment. The leadership of the South PIC shared ideas and resources throughout the spring semester, leveraging our network to provide lessons learned and moral support. Our 2020 South PIC meeting was devoted to discussing how we will continue our inclusive excellence work as our universities continue to evolve in response to the pandemic. Learning together has taken on a heightened significance as we simultaneously navigate uncharted and age-old challenges to inclusion. We look forward to sharing future results of our individual and collective project evaluations.

7 Acknowledgements

We thank the Howard Hughes Medical for Institute Inclusive Excellence grants to Radford University, Towson University, Trinity Washington University, and Virginia Tech. We thank ASCN for the opportunity to present at the 2019 Transforming Institutions Conference and submit this chapter.

8 About the Authors

Jeremy Wojdak is a Professor of Biology in the Artis College of Science and Technology at Radford University.

Tara Phelps-Durr is a Professor of Biology in the Artis College of Science and Technology at Radford University.

Laura Gough is Professor and Chair of the Department of Biological Sciences at Towson University.

Trudymae Atuobi is the Student Success Program Coordinator and Adjunct Professor of Biology at Towson University.

Cynthia DeBoy is a Clare Boothe Luce Associate Professor of Biology in the College of Arts and Sciences at Trinity Washington University.

Patrice E. Moss is a Clare Boothe Luce Associate Professor and Chair of the Biology Program at Trinity Washington University.

Jill Sible is the Associate Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education and a Professor in Biological Sciences at Virginia Tech.

Najla Mouchrek is the Program Director for Interfaith Leadership and Holistic Development at Virginia Tech.

9 References

Auchincloss, L. C., Laursen, S. L., Branchaw, J. L., Eagan, K., Graham, M., Hanauer, D. I., Lawrie, G., McLinn, C. M., Pelaez, N., Rowland, S., Towns, M., Trautmann, N. M., Varma-Nelson, P., Weston, T. J., & Dolan, E. L. (2014). Assessment of course-based undergraduate research experiences: A meeting report. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-01-0004

Bangera, G., & Brownell, S. E. (2014). Course-based undergraduate research experiences can make scientific research more inclusive. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(4), 602–606. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-06-0099

Bass, R., Eynon, B., & Gambino, L.M. (2019). The new learning compact: A framework for professional learning and educational change. Every Learner Everywhere. https://www.everylearnereverywhere.org/wp-content/uploads/NewLearningCompact.pdf

Beichner, R. J., Saul, J. M., Abbott, D. S., Morse, J. J., Deardorff, D. L., Allain, R. J., Bonham, S. W., Dancy, M. H., and Risley, J. S. (2007). The Student-Centered Activities for Large Enrollment Undergraduate Programs (SCALE-UP) project. Research-Based Reform of University Introductory Physics, 1(1), 2–39. http://www.per-central.org/document/ServeFile.cfm?ID=4517

The Carnegie Classifications of Institutions of Higher Education. (n.d.). About Carnegie Classification. http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/

Clayton-Pedersen, A. R., O’Neill, N., & McTighe Musil, C. (2017). Making excellence inclusive: A framework for embedding diversity and inclusion into colleges and universities’ academic excellence mission. Association of American Colleges & Universities. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/mei/MakingExcellenceInclusive2017.pdf

Eddy, S.L., and Hogan, K.A. (2014). Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 453–468. https://doi.rg/10.1187/cbe.14-03-0050

Finkelstein, N., Greenhoot, A. F., Weaver, G., & Austin, A. E. (this volume). “A department-level cultural change project: Transforming the evaluation of teaching.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 14). Pressbooks.

Gardner, G., Ridgway, J., Schussler, E., Miller, K., & Marbach-Ad., G. (this volume). “Research coordination networks to promote cross-institutional change: A case study of graduate student teaching professional development.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 10). Pressbooks.

Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011) Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48, 952–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20439

Howard Hughes Medical Institute. (n.d.). Inclusive Excellence. Howard Hughes Medical Institute. https://www.hhmi.org/science-education/programs/inclusive-excellence

Johnson, E., Andrews-Larson, C., Keene, K., Melhuish, K., Keller, R., & Fortune, N. (2019). Inquiry does not guarantee equity. Proceedings of the annual conference on research in undergraduate mathematics education. The Special Interest Group of the Mathematics Association of America (SIGMAA) for Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education. http://sigmaa.maa.org/rume/crume2019/Papers/37.pdf

Kezar, A., & Miller, E. R. (this volume). “Using a systems approach to change: Examining the AAU Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 9). Pressbooks.

Lee, J. Y., Khalil, D., & Boykin, A. W. (2019) Enhancing STEM teaching and learning at HBCUs: A focus on student learning outcomes. Student Services, 167, 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20318

Lisberg, A., & Woods, B. (2018). Mentorship, mindset and learning strategies. Journal of STEM Education, 19(3), 14–19. https://www.jstem.org/jstem/index.php/JSTEM/article/view/2280/1964

Marbach-Ad., G., Hunt, C., & Thompson, K. V. (this volume). “Using data on student values and experiences to engage faculty members in discussions on improving teaching.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 8). Pressbooks.

Margherio, C., Doten-Snitker, K., Williams, J., Litzler, E., Andrijcic, E., & Mohan, S. (this volume). “Cultivating strategic partnerships to transform STEM education.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 12). Pressbooks.

Neumann, A. (2005). Observations: Taking seriously the topic of learning in studies of faculty work and careers. In E. G. Creamer & L. R. Lattuca (Eds.), Advancing faculty learning through interdisciplinary collaboration [Special issue]. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 102, 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.197

O’Meara, K., Jaeger, A., Misra, J., Lennartz, C., & Kuvaeva, A. (2018). Undoing disparities in faculty workloads: A randomized trial experiment. PloS One, 13(12), e0207316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207316

Oufiero, C. E. (2019) The organismal form and function lab-course: A new CURE for a lack of authentic research experiences in organismal biology. Integrative Organismal Biology, 1(1), obz021. https://doi.org/10.1093/iob/obz021

President’s Council of Advisors for Science and Technology. (2012). Engage to excel: Producing one million additional college graduates with degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED541511.pdf

Sebesta, A. J., & Bray Speth, E. (2017). How should I study for the exam? Self-regulated learning strategies and achievement in introductory biology. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(2), ar30. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-09-0269

Setren, E., Greenberg, K., Moore, O., & Yankovich, M. (2019). Effects of the flipped classroom: Evidence from a randomized trial. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://edworkingpapers.org/sites/default/files/ai19-113.pdf

Shaffer, C. D., Alvarez, C., Bailey, C., Barnard, D., Bhalla, S., Chandrasekaran, C., Chandrasekaran, V., Chung, H.-M., Dorer, D. R., Du, C., Eckdahl, T. T., Poet, J. L., Frohlich, D., Goodman, A. L., Gosser, Y., Hauser, C., Hoopes, L. L. M., Johnson, D., Jones, C. J., … Elgin, S. C. R. (2010). The genomics education partnership: Successful integration of research into laboratory classes at a diverse group of undergraduate institutions. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 9(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.09-11-0087