20 Transforming the teaching of thousands: Promoting evidence-based practices at scale

Kay Halasek, Andrew Heckler, and Melinda Rhodes-DiSalvo

1 Introduction

A variety of models of higher education institutional change focus on improving instruction, including examples of initiating such change at all levels from individual faculty to multi-institutional collaborations. In this paper, we describe, analyze, and reflect upon the change process for implementing a recent and ongoing institution-wide teaching enrichment program from both diachronic and synchronic perspectives. Envisioned and initiated by the university president, the Teaching Support Program (TSP) at The Ohio State University has engaged over 82% of full-time tenure- and clinical-track faculty and lecturers from undergraduate-serving colleges.

In this chapter, we consider the change process from two nested theoretical perspectives. The first comprises the comprehensive framework of four categories of change strategies by Henderson et al. (2011) (see also Borrego & Henderson, 2014). Although this framework was constructed with special attention to STEM higher education research, it was also based on the work of faculty development and higher education researchers, and we assume here that it is suitable for university-wide application. The second perspective is Kotter’s (1996) model, which articulates an eight-step process for leading institutional change. We briefly describe these theoretical frameworks in the next section.

Working from these conceptual frameworks, we retrospectively analyze recent and ongoing institutional change processes through a synchronic analysis, which takes a deep dive into a critical point during the life of institutional change, to investigate how simultaneously occurring and dynamic factors, features, and values (both aligned and conflicting) impact and oftentimes have significant implications for institutional change. Our goal is not to contest others’ models but to supplement them in an effort to demonstrate that examining discrete, synchronic, changes in institutional contexts offers insights into understanding and implementing change through responsive action—a phenomenon we understand metaphorically as a shifting or realignment of gears.

2 Theories of Institutional Change

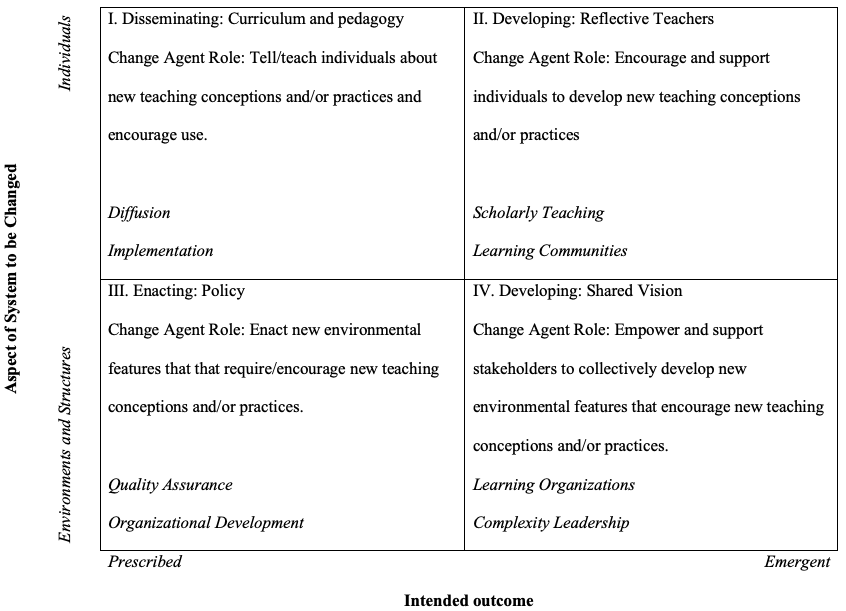

Henderson et al.’s (2011) four categories of change strategies (Figure 1) are described in detail in several papers (e.g. Borrego & Henderson, 2014).

Through a comprehensive analysis of the literature, Henderson et al. (2011) identified two binary dimensions of primary importance with respect to institutional change strategies. The first dimension relates to what aspect of the system is targeted for change. They identified two discreet possibilities: individuals and environments and structures. In the second dimension, related to the nature of the outcome, they again identified two discreet possibilities: prescribed and emergent. These two binary dimensions result in the four possible categories. For example, consider Category III: Enacting Policy, which lies at the intersection of Prescribed and Environments and Structures, and is relevant to our analysis. This strategy is characterized by enacting new policies that “[guide] organizations (and the people within them) towards a pre-identified goal” (Borrego & Henderson, 2014, p. 235), such as adopting evidenced-based teaching practices. In contrast to Salomone et al. (this volume) and Klein et al. (this volume), who implemented bottom-up models of institutional change, we pursued a top-down approach that employs the underlying logic that “instruction will be changed by administrators with strong vision who can develop structures and motivate faculty to adopt improved instructional practices” (Borrego & Henderson, 2014, p. 237). It important to note that Borrego & Henderson place Kotter’s (1995, 1996) top-down model of change within the Category III strategy. Kotter (1995, 1996) sets out an eight-step process of organizational transformation. Although later revised into a more dynamic model in which “steps” were redefined as “accelerators” of change deployed “concurrently and continuously” (Kotter, 2014, pp. 27–34), the process retains roughly the same set of steps: 1) establish an exigence, 2) form a coalition, 3) articulate a vision, 4) communicate that vision, 5) empower others to act, 6) create short-term wins, 7) consolidate improvements to produce additional change, and 8) institutionalize change (Kotter, 1995, p. 61).

The TSP and other University Institute for Teaching (UITL)[1] programs and activities impacting the teaching culture at Ohio State map effectively onto the four categories of Henderson et al. (2011) (see Table 1). Categories I and II (with their emphasis on individual change and outcomes) align with the phases of the Teaching Support Program, while Categories III and IV extend impact through changes in and outcomes for the institutional environment and structures.

| Henderson et al. Category | Aligned Program or Activity |

| Category I: Disseminating curriculum and pedagogy | TSP Phases I and II |

| Category II: Developing reflective teachers | TSP Phase III |

| Category III: Enacting policy | Adopt evidence-based practices |

| Category IV: Developing shared vision | UITL Affiliates and Alliance program |

We recognize that while all four categories (Borrego & Henderson, 2014) are relevant to the program we analyze, we focus here on Category III. In the course of our investigation, we realized that this relatively rarely used strategy fits well with the strategy used at our institution. However, we also found that analyzing the institutional changes at our institution in terms of Category III and Kotter’s model requires a modified, more synchronic perspective of the change process, as we discuss below.

3 Leaders’ Visions for Change

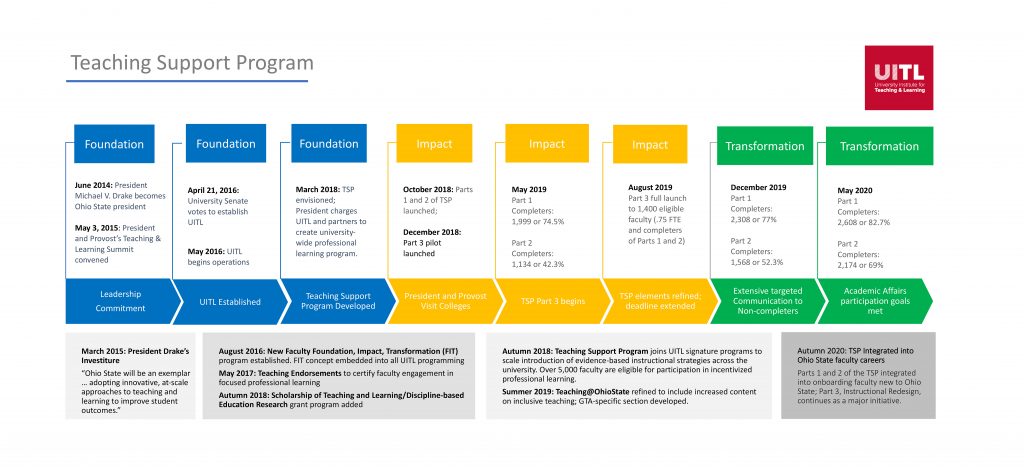

To analyze retrospectively the change and decision-making philosophies of university leaders and gather their perspectives on future directions for effecting change in the teaching culture at the University, we conducted interviews with both Ohio State University President Michael V. Drake and Provost Bruce A. McPheron about their vision for the UITL and its signature Teaching Support Program (TSP), a three-part professional learning initiative launched in 2018. Figure 2 depicts the chronology of UITL and the TSP.

Intended to engage all faculty across all six campuses of the University in learning about and deploying evidence-based practices in their teaching, the TSP comprises a validated Teaching Practices Inventory (TPI) (Weiman & Gilbert, 2014) that promotes self-reflection (Part 1); a five-module online Teaching@OhioState course on evidence-based practices and purposeful immersion in those practices and the research supporting their implementation through reflecting upon selections from a curated reading list (Part 2); and an opportunity to engage in instructional redesign, implementation, and assessment (Part 3).

Part of an IRB-approved research project, the interviews were designed to gain insight into administrative perspectives on the implementation of UITL and leaders’ theories of change and their strategies, tactics, goals, and general views of the institute and its signature program. (See Appendices 1 and 2 for interview questions.)

The interviews demonstrate that, in action at an institutional level at Ohio State, Kotter’s (1996) model of change holds conceptually—as President Drake’s comments in his interview bear out. He remembers clearly encountering Kotter during a seminar he attended some 15 years earlier: “We had him for two days, and he … was totally invested in … the idea of having an authentic concept of what you want to have happen, and then having people around you … to support that and then relentlessly following up with that … [and] communicating, over-communicating … short-term wins and continuing that feedback.” He subscribes to Kotter’s model, noting the various stages and engagements as aligning with his strategic leadership approach. He also mentions, for example, that he identified an urgency, an exigence, for the initiative. (In fact, he identified two exigencies, a matter we address below.) He also speaks to identifying and engaging stakeholders and volunteers in the earliest stages. Faculty leaders (e.g., those individuals recognized as exceptional teachers, faculty from the College of Education and Human Ecology, representatives from all campuses, and a broad range of colleges and appointment types) met in a series of convenings to collectively envision the Institute, and he seeks “small wins.” “We took the Kotter model of eight people in the corporation and modeled it at a university and had 80 people” as part of the guiding coalition that led to the creation of the UITL in 2016.

In both interviews, the leaders demonstrate a commitment to “considering the ‘why’ and ‘what’ of change first” (Kezar, 2018, p. 1): positively impacting undergraduate student success by encouraging faculty reflection on and continued professional learning in support of their teaching. Although certainly situated within and recognizing the political context and external pressures to which university leaders must attend, both the president and provost attend to the motivations for change as situated within and driven by the mission of the University. Both take seriously and acknowledge their roles in “setting a direction” (Kotter, 2014, p. 60) and articulating a clear vision and reasons for change, a point the provost makes explicitly when he reflects on the staying power of the president’s vision, noting the “consistency with which we have anchored back to [the president’s investiture speech]…. That was maybe eight, nine, ten months into his tenure, and we find ourselves talking about the 2020 vision all the time.” In his interview, the provost also acknowledges the power of leaders to affect change when he notes that “just this notion of getting people talking about teaching and learning in yet another way—I think that that central drive from the president, from him motivating all of us around him … to really dig into that has been incredibly important. It has been essential, really, to getting where we are.”

At the same time, the leaders acknowledge that their initial visions—which were informed by the through-line of engaging faculty with the goal of positively impacting undergraduate student success—were complicated by two specific institutional realities. Associated faculty and graduate students play prominent and critical instructional roles, particularly in the first two years of the undergraduate and general education curriculum and in “stumbling block” courses. Not initially among the faculty groups to whom base salary increases were extended, full-time associated faculty argued successfully for identical compensation for completing the TSP.[2] As the provost frames it, leaders were “making sure that we were hearing the voices of the associated faculty because they actually often track back to the very classes and students that … we were most concerned about from the start.” Graduate teaching associates (GTAs) (particularly in the arts and sciences) also teach in the undergraduate and general education curriculum and in “stumbling block” courses, a matter that the president notes led to modifications in the timeframe and scope of the initiative. A GTA-specific version of the online course, Teaching@OhioState, was launched in Fall 2018, the first step in recognizing graduate students’ critical role in impacting student learning outcomes and realizing the president’s goal of also “making graduate students better teachers.”

4 Perspectives of UITL Leadership

Kotter’s (1996) model holds conceptually, as we note above. However, in practice, individual initiatives exist alongside one another, bumping up against or moving forward with them. In any large institution, models of change—instances of initiatives intended to leverage change—often run concurrently, synchronously. Successful change on an institutional level of any one of the initiatives is dependent upon its relationship to the others. In short, the degree of alignment between or among these various initiatives stands as perhaps the most critical matter when we reflect on the implementation of the TSP at Ohio State.

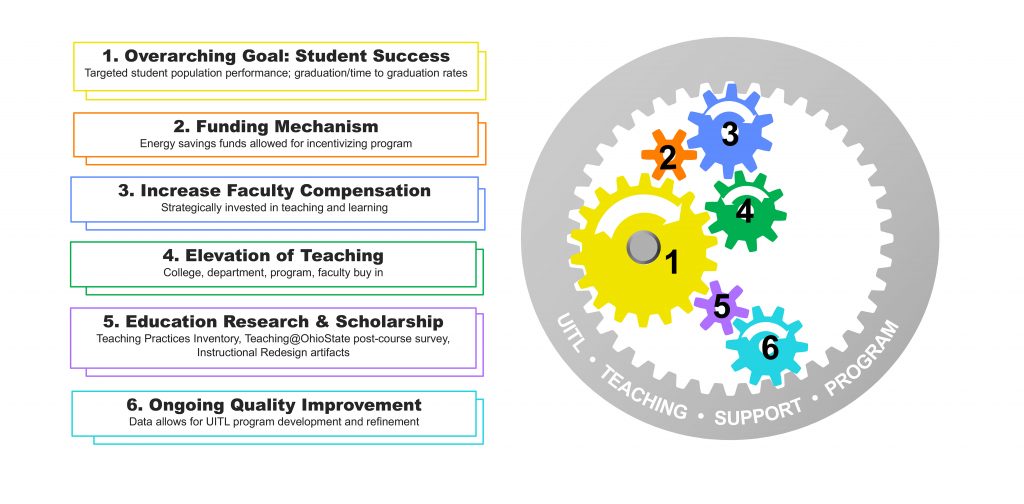

To better account for the dynamic nature of institutional initiatives and their relationships, we examined them both synchronically (existing at a given time) and diachronically (unfolding over time) and in concert with the other efforts. This kind of analysis offers a means of complicating—nuancing—Kotter’s (1996) framework. Rather than only understand the establishment of UITL or creation of the TSP in situ—in only its origin form—and examining it alone, we find greater benefit to examining the larger ecosystem of institutional features, values, and initiatives and how they inform, impact, complicate, and even potentially compromise one another at a given time. We have come to think of these various initiatives as sets of interlocking gears (Figure 3).

The rotation and turn ratio of the gears are dependent upon one another; they must work in tandem for institutional leaders to realize desired outcomes. A gear that slips stalls the others. A gear that turns counter to the whole grinds them all to a halt, as does a foreign object inserted or jammed into the mechanism. The importance of this systemic metaphor was evident to President Drake, who used open and separated hands to indicate the starting point, “we were here,” and then interlocked his fingers, “and ended with this.” When larger and smaller gears mesh, mechanical advantages are produced, yet when several gears are involved, inevitable frictions require more effort to turn and keep them moving, much like interlocking programs and policies at an institution.[3]

The most salient example of this interlocking gears model relates to the pairing of three strategic institutional goals: impacting undergraduate student success (Gear 1), increasing faculty salaries relative to other Big Ten institutions (Gear 3), and elevating teaching and learning (Gear 4). In speaking to his own model for institutional change, the president noted the importance of creating contexts that motivate people to engage in particular behaviors that also align with their personal interests (“easy to do, fun to do, and in their personal interest to do so”). The ease of engagement or compliance arose as a theme in the President’s interview. By tying together two goals, which he noted were initially “entirely separate,” he created a context that encouraged and rewarded faculty engagement in professional learning (Gear 4) and had the collateral effect of raising faculty salaries (Gear 3).

5 Evidence of Success

Throughout the process of implementation, we have gathered participation and qualitative data that speak to the breadth of engagement among faculty and their reception of the program—two factors integral to the continued growth of and impact on a robust culture of teaching through evidence-based practices that impact student outcomes.

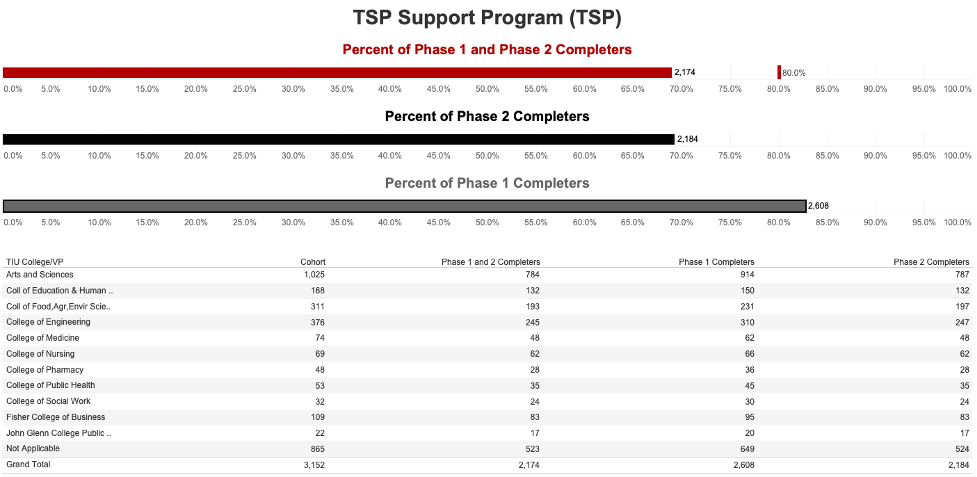

By May 15, 2020 (at the close of incentivized participation), 2,608 eligible faculty (82.7%) in undergraduate-serving colleges had completed Part 1; 2,174 (69%) had completed both Parts 1 and 2. More detailed participation statistics appear in Figure 4.

Survey results in Table 2 indicate positive views and reception of the online course and suggest that faculty participants are reflecting on evidence-based practices, an important component of instructional professional development.

| Survey Item | % agree or highly agree | Total Number of responders |

| The course was helpful. | 88.77 | 2,601 |

| The course was relevant to my teaching. | 85.17 | 2,602 |

| I would recommend the course to a colleague. | 82.86 | 2,603 |

| The course provided me with multiple perspectives on teaching and learning. | 94.09 | 2,621 |

| The course exposed me to evidence-based practices. | 92.67 | 2,618 |

| The course encouraged me to reflect on my teaching practices. | 94.19 | 2,615 |

| I will apply what I learned from this course to improving my teaching practices. | 93.32 | 2,605 |

UITL has also gained through its analysis of these and other data (such as phone logs and emails) insight into factors that influence faculty engagement in professional learning and the contexts, characteristics, and strategies of academic units with the highest completion rates. For example, a survey of non-completers revealed that the most frequently cited barriers were time to complete the program and lack of awareness of the program or their own eligibility for financial incentives. Departments and colleges with leadership who actively reached out to faculty to encourage engagement and congratulate completers were, not surprisingly, those with the highest completion rates.

UITL received feedback from faculty through dozens of emails and calls received each day for the first month after the program was launched in Fall 2018. In addition to clarifying participation processes and confirming compensation eligibility, these calls and email exchanges, although anecdotal evidence, nonetheless served as productive means of gathering feedback on the program that allowed UITL to make adjustments to the course content, further refining it to address faculty articulated needs and interests. During the first few months of deployment, designers clarified questions in module quizzes and later created additional content and resource links on inclusive teaching and working with international students. A customized version of the course focusing on the needs of GTAs was created in 2019, and over 800 GTAs new to their teaching appointments in 2019–2020 were enrolled.

The TSP has now reached the close of its incentive phase (May 15, 2020) as an initiative to support continued professional learning among all instructors at the university. Direct measures of changes in instructional practice and impact on undergraduate student success are the gold standard for documenting impact of the initiatives; however, full evaluation of the impact of the TSP has not yet begun and is beyond the scope of this chapter. Future research activities include examining the TPI for various trends in self-reported use of evidence-based practices, coding post-course satisfaction and implementation surveys in the online Teaching@OhioState, and coding and conducting qualitative analyses of UITL reading reflection submissions for trends in and across instructional contexts, subject matters, and disciplinary applications. Part 3 of the TSP (launched in Spring 2019), which engages faculty in instructional redesign, implementation, and assessment of instruction and includes faculty portfolio artifacts and assessment reports, will allow UITL to begin analyzing TSP impact on student learning at the classroom, department, and program level.

6 Reflections and Next Steps

Analyses by multiple researchers have made it clear that lasting and meaningful improvement of instruction in higher education cannot involve just one approach; rather, it requires holistic, multifaceted strategies (Cook-Sather et al., this volume; Corbo et al., 2016; Henderson et al., 2011; Kezar, 2018; Klein et al., this volume). In our case study, university leaders were deeply engaged in the institutional change: They initiated (and continued oversight of) the effort, and this involvement of leadership cued us to more deeply consider top-down approaches in our analysis. From the perspective of Henderson et al.’s (2011) framework, this involved a closer examination of Category III: Enacting Policy, and Kotter’s model, which is a related top-down model. It is by synchronically examining this institutional change, as evidenced for example by the creation, implementation, and success (to date) of the TSP, that we discovered that the top-down strategy involved multiple aspects of the university, including aspects of the university not typically seen as directly related to instructional improvement (see Figure 3.) One might in fact view this as a native advantage of a strong top-down component to a university change strategy, and this strategy has a clear need for engagement by the institutional leadership.

Our observation of the purposeful engagement of separate yet inevitably interacting university-wide features, values, and initiatives also uncovered a need to more carefully characterize the multi-component complexity of a top-down strategy as “tied to the culture and process … at multiple levels” (Klein et al., this volume). One cannot simply consider a change as singular or isolated, such as “improving instructional practice” but must also consider the implications on multiple, large-scale institutional policies and practices. In retrospect, we find Kezar’s (2018) critique of Kotter’s eight-stage process (which she describes as “helpful” but ultimately “too simple, linear, and generalized” [p. xii]) to account for the complex systems and multiple categories of change strategies that were concurrently implemented in the TSP. In fact, culture change relies on different primary strategies at different points along a timeline; moreover, the length of time from initiative creation to culture change might be compressed with a conscientious shift from Category IV to Category III once a certain consensus or agreement has been established.

Considering our metaphor of gears in a complex system, institutions and organizations seeking to change culture through a set of incentives are best served when executive leadership positions the change mechanism as a priority.[4] This top-down approach ensures the cooperation of necessary offices and a solutions mindset among units that will implement policy and incentive structures. In addition, once the goals and outcomes of culture change mechanisms have been articulated, leaders of necessary support offices must be brought to the table to identify and articulate challenges and solutions. Moreover, given the complex mechanisms required to both develop and successfully launch a multi-part faculty professional learning program to influence culture that relied as much on structural support as on champions, this careful and considered promotion of change by top leadership is essential, effective, and, perhaps, preferred. Such a “top-down” model to focus attention and initiate change is, in fact, preferable, if not necessary—as President Drake and Provost McPheron both noted in their interviews—in institutions as large as Ohio State. As faculty and staff in the UITL, we were charged not only with implementing (enlisting volunteers, enabling action, and generating short-term wins) but also leading, nurturing, and sustaining the guiding coalition. The top-down charge provided the Institute with the rationale for calling together collaborators and for those collaborators to elevate the work of the coalition internally.

At the same time, sustaining such change in a teaching culture over time, as anecdotal evidence suggests, cannot rely solely on the vision articulated by leadership. As acknowledged, for example by Henderson et al. (2011), there is an inherent danger to implementing a top-down strategy, namely that a one-size-fits-all approach ignores critical local contextual factors. On the other hand, a bottom-up approach risks actions at odds with the university system and not institutionally sustainable. Deploying top-down strategies encompassing multiple aspects of the university structure allows for productive alignment and lasting, systemic institutional change, a conclusion also reached by Klein et al. (this volume). Given this understanding, UITL—along with departmental leaders—must next take up the banner. Looking forward toward creating sustainable change, we recognize the value of engaging Kezar’s (2018) six perspectives as means of anchoring that change (p. 44). Perhaps our greatest challenge will be moving from the individualized incentive and reward structure of the TSP (a form of scientific management in Kezar, 2018) to voluntary (but expected) participation.[5] Central to this shift will be engaging the social, cultural, and political perspectives that acknowledge the critical role of change agents in a variety of activities: agenda setting, coalition building, mapping power structures, and negotiating (Corbo et al., 2016, p. 6). We have identified the importance of creating formal alliance structures with department chairs and establishing a faculty fellows’ network in departments as among our next steps, initiatives not unlike those described by Nelson and Hjalmarson (this volume), Greenhoot et al. (this volume), Chasteen et al. (this volume), and others.

Rather than focusing only or primarily on aligning UITL activities to the University strategic plan, we now recognize that the success of the Institute and TSP in particular are a function of an alignment between and among the gears (Figure 3) driving and impacting the culture of teaching at the University. Institutional change takes place over time and, understandably, models of institutional change (e.g., Kotter, 1996; Borrego & Henderson, 2014) conceptualize and consider means of facilitating that change over time—diachronically. By also examining change synchronically and analyzing critical points during the life of institutional change, as we do here, we have investigated how simultaneously occurring and changing factors, features, and values impact and oftentimes have significant implications for institutional change. Higher education leaders seeking to change culture might benefit from considering more explicitly how even seemingly diverse objectives might be served or aligned when promoting or developing change mechanisms.

7 About the Authors

Kay Halasek is the Director of the Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning and professor of English at The Ohio State University.

Andrew Heckler is Professor of Physics at the Ohio State University and Research Fellow for the OSU Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning.

Melinda Rhodes-DiSalvo, Ph.D., is Associate Director for Strategic Partnerships and Operations with the Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning at The Ohio State University.

8 References

Borrego, M. & Henderson, C. (2014). Increasing the use of evidence-based teaching in STEM higher education: A comparison of eight change strategies. Journal of engineering education, 103(2), 220–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20040

Chasteen, S., Code, W., & Sherman, S. B. (this volume). Practical advice for partnering with and coaching faculty as an embedded educational expert. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 21). Pressbooks.

Cook-Sather, A., White, H., Aramburu, T., Samuels, C., & Wynkoop, P. (this volume). Moving toward greater equity and inclusion in STEM through pedagogical partnership. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 15). Pressbooks.

Corbo, J. C., Reinholz, D. L., Dancy, M. H., Deetz, S., & Finkelstein, N. (2016). Framework for transforming departmental culture to support educational innovation. Physical Review—Physics Education Research, 12(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.010113

Greenhoot, A. F., Aslan, C., Chasteen, S., Code, W., & Sherman, S. B. (this volume). Variations on embedded expert models: Implementing change initiatives that support departments from within. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 21). Pressbooks.

Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of research in science teaching, 48(8), 952–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20439

Kezar. A. J. (2018). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change. Routledge.

Klein, C., Lester, J., & Nelson, J. (this volume). Leveraging organizational structure and culture to catalyze pedagogical change in higher education. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 19). Pressbooks.

Kotter, J. P. (1995). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard business review, 73(2), 59–67. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Harvard Business School Press.

Kotter, J. P. (2014). Accelerate: Building strategic agility for a faster moving world. Harvard Business Review Press.

Nelson, J. K., & Hjalmarson, M. A. (this volume). Discipline-based teaching development groups: The SIMPLE framework for change from within. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 18). Pressbooks.

Salomone, S., Dillon, H., Prestholdt, T., Peterson, V., James, C., & Anctil, E. (this volume). Making teachers matter more: REFLECT at the University of Portland. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 17). Pressbooks.

Weiman, C., & Gilbert, S. (2014). The teaching practices inventory: A new tool for characterizing college and university teaching in mathematics and science. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-02-0023

9 Appendix

9.1 President Interview Questions

- When you reflect on the establishment of the University Institute for Teaching and Learning and the Teaching Support Program in particular, how would you describe your strategic approach for affecting change at an institutional level? What was/were the critical problem or problems you saw the TSP initiative addressing?

- What were your primary motivations for launching the TSP? What were your most salient objectives?

- What change or leadership scholarship or models of institutional change do you read or call upon—especially with regard to UITL and the TSP? What critical applications or practices do you derive from that scholarship?

- As we have been reflecting on our work in UITL, we have come to realize that the change associated with the TSP shares characteristics with “top-down” theories of change, like Kotter’s (1995, 1996). Models like Kotter’s state that change can be driven by “administrators with strong vision who can develop structures and motivate faculty to adopt improved instructional practices” (Borrego & Henderson, 2014, p. 237) Did you have a model like Kotter’s in mind as you conceived of UITL and the TSP? In what ways did those models shape your approach and vision?

- When undertaking large-scale institutional change (as you did through UTIL with the TSP), how did you reconcile the affordances and constraints of a top-down versus a constituent-driven or bottom-up approach to change?

- What barriers to development and implementation of the TSP did you anticipate? Which of those were most challenging? What other, unexpected, barriers arose? How did you address them?

- Moving forward, what strategies you anticipate using to sustain your effort to transform the university culture around teaching?

9.2 Provost Interview Questions

- When you reflect on the establishment of the University Institute for Teaching and Learning and the Teaching Support Program in particular, how would you describe the strategic approach for affecting change at an institutional level? What was/were the critical problem or problems you saw the TSP initiative addressing?

- What would you identify as the primary motivations for launching the TSP? What were the most salient objectives?

- When undertaking large-scale institutional change (as OSU did through UTIL with the TSP), how would you reconcile the affordances and constraints of a top-down versus a constituent-driven or bottom-up approach to change?

- What barriers to development and implementation of the TSP did you anticipate? Which of those were most challenging? What other, unexpected, barriers arose? What strategies did the University use to address them?

Moving forward, what strategies you anticipate the University using to sustain its effort to transform the university culture around teaching?

[1] In June 2020, the University Institute for Teaching and Learning was renamed in honor of President Michael V. Drake, becoming the Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning. Because the incentivized TSP described here was implemented before the change in the name of the institute, we have elected in this chapter to retain references to the UITL.

[2] The financial structure for full-time tenure-track, clinical, and associated faculty included a $400 increase to base salary for completing Part 1, a $1,200 increase to base salary for completing Part 2, and a $1,150 one-time cash stipend for completing Part 3. Part-time tenure track and clinical faculty received one-half the base pay compensation for Parts 1 and 2. Part-time associated faculty (lecturers) received one-time payments of $200 and $600 but are not eligible for Part 3. Because one of the goals leadership articulated involved increasing OSU faculty salaries relative to the median in the Big 10, that measure in future years will be a partial indicator of program success.

[3] Salomone et al. (this volume), as well, note the importance to align work with mission of university and leadership and “strategically leverage other activities on campus” as a means of realizing goals.

[4] Cook-Sather et al (this volume), Salomone et al. (this volume), and Greenhoot et al. (this volume) also deployed financial incentives as features of their programming. Greenhoot et al. speak to the significant value of financial incentives and major institutional investments in programs to support teaching enrichment programs, naming funding as a “critical lever for promoting buy-in and engagement from department faculty and leadership”.

[5] The incentive structure noted above ended in May 2020. Subsequently, completion of the TSP will be an expectation of hire for faculty new to the university.