9 Using a Systems Approach to Change: Examining the AAU Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative

Adrianna Kezar and Emily Miller

1 Introduction

While systems theory is widely known to help foster change, most change efforts in STEM reform do not utilize a systems approach (Austin, 2011; Kegan, & Lahey, 2009). This chapter reports on the Association of American Universities’ (AAU) Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative (“Initiative”) effort to improve the effectiveness of undergraduate science and mathematics education at research universities and its application of a systems approach to change. While several chapters in this volume speak to parts of the system (departments, colleges, institutions), none focus on how to connect across multiple parts of a system and align them to promote change—the focus of this chapter.

In 2011, AAU launched the Initiative in collaboration with member institutions aimed at influencing the culture of STEM departments at AAU institutions so that faculty are encouraged to and supported in use of teaching practices proven by research to be more effective in engaging students in STEM education and in helping students learn (AAU, 2017b). Over the course of the initiative, AAU member institutions have documented improvement in undergraduate student learning within foundational STEM courses (AAU, n.d.). In addition, the association has identified broader outcomes (e.g. cross-cutting institutional strategies for change) from campuses collaborating and leveraging one another within the network as well as key strategies that worked across multiple levels to create synergy across the system. And the Initiative resulted in other key outcomes such as including language in key legislation—The American Innovation and Competitiveness Act. Thus, outcomes have ranged from transforming departments and improving student outcomes, to new institutional policies and practices, to cross-campus initiatives, to federal legislation—all detailed below.

This chapter documents the three major domains of the system that the Initiative was aimed at influencing 1) the institutional level, 2) the network level, and 3) the national level) in order to comprehensively impact undergraduate STEM reform. This three-domain strategy demonstrates a systems approach in action. Furthermore, the Initiative leveraged the interaction among the three domains and was intentional in attending to the multiple levels and stakeholders within each domain to generate greater synergy within and between each domain. Leveraging more parts of the system leads to greater likelihood of change (Austin, 2011, 2014; Kezar, 2018a). This chapter amplifies the findings about the importance of networks and partnerships noted by other chapters in this volume by Gardner et al., Wojdak et al., and Margherio et al. We also document how networks help facilitate learning to promote change and spread through connecting change agents, similar to other chapter authors.

2 Why Systems Change

Studies from systems theory demonstrate that an organizational entity and social system is made up of an underlying set of structures (e.g. facilities, technology), policies (e.g. promotion and tenure), and processes (e.g. teaching and learning) (Kezar, 2018a; Toma, 2010; Willis et al., 2014). These various underlying aspects are often referred to as the “infrastructure.” When these aspects of the system are aligned to support a change initiative, then the transformation is more likely to occur and to be sustained (Toma, 2010). Research demonstrate that transformation efforts that do not modify the underlying structures and processes typically fail, experience challenges or are not sustained (Kezar, 2018a; Smith, 2015; Toma, 2010).

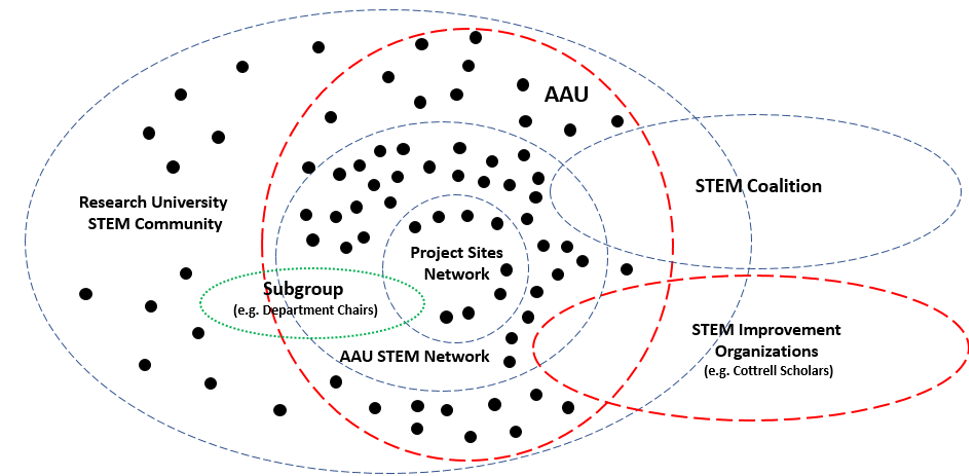

From the beginning, AAU used broader theoretical perspectives about organizational change in academia and systems theory to guide the planning and direction of the Initiative. Ultimately, the association’s approach to systemic and sustainable change to undergraduate STEM teaching and learning was grounded in a more nuanced consideration of factors that facilitate, impede, or influence wide-spread transformation in undergraduate education (Miller et al., 2017). The aim was to embed changes into the fabric of the systems—structures, process, and policies—to increase the likelihood that changes will be permanent and result in a cycle of continuous improvement of teaching and learning (Kegan & Lehay, 2009). In Figure 1, we illustrate the various networks that AAU created to help support systemic change. The networks include 1) the eight project sites, 2) the AAU STEM network, 3) the AAU network, 4) departmental networks that connected across AAU and non-AAU institutions, 5) the research university STEM community connected across AAU and non-AAU institutions, 6) a STEM coalition that included members of national organizations, and 7) a network of organizations aimed at improving STEM education.

3 The Institutional Level

AAU leaders recognized that the institutional level was extremely important for creating systemic changes because policy, rewards, incentives, resources, and norms that guide practice all are created and reinforced at the institutional level. In order to shape institutional processes, several key efforts were undertaken including a framework that identifies the key aspects of institutions that could be leveraged for change, funding project sites that would serve as laboratories and models of change, and reporting that would hold institutions accountable for action.

3.1 Institutional Change Framework

AAU created a Framework for Systemic Change in Undergraduate STEM Teaching and Learning (“Framework”) (AAU, 2013). The Framework recognizes the wider setting in which educational innovations take place—the department, the college, the university, and the national level—and addresses the key institutional elements necessary for sustained improvement to undergraduate STEM education. The three layers of the Framework are: 1. Pedagogy—which involves assisting faculty in creating learning goals, assessments, and other practices that support new evidence-based teaching practices; 2. Infrastructure—such as workshops from the centers for teaching and learning, and technology and facilities that support new evidence-based teaching practices; and 3. Cultural change—support at the institutional level such as changes in promotion and tenure, and commitment to sustaining successful strategies by senior leaders. Given the novelty of working at the institutional level to support new teaching practices, the purpose of the Framework was to provide necessary guidance and expectations for institutions to participate in the Initiative.

3.2 Initiative Project Sites

AAU established a competition to identify a pilot cohort of eight institutions among AAU membership. The request for proposals was ground in the Framework, established a set of institutional-level expectations, and created a context where institutions had to identify the readiness of departments to engage in redesigns of introductory courses. AAU recognized that academic departments are a primary locus for cultural change, and that academic units and colleges are central to improving the quality of undergraduate education. Furthermore, academic departments are powerful and have significant structures of influence. However, AAU choose a strategy of granting institutional rather than departmental awards and established expectations for institution to support departmental activities because institutions are a primary site for sustaining changes.

Departmental and project-based interventions often are not sustained due to lack of support or compatibility with the overall institution (Beach et al., 2012). Tenure and promotion policies, inadequate facilities, missing professional development, and other barriers often shape the uptake (or not) of initiatives (Kezar, 2018a). Hence, making the institution the level of change was an intentional effort to overcome failed change efforts of the past. One way that this initiative differentiated itself from other efforts to improve undergraduate STEM education was that the Initiative emphasized not just individual or departmental change, which has been the focus of many previous STEM projects, but institutional-level change. The idea that change cannot be scaled and sustained unless the overall institution supports the change was relatively novel within this approach when it began in 2013.

Although many of the Initiative interventions are still in process, initial data demonstrates their positive impact. Of the eight initial project sites, all have reported some improvement in student learning outcomes. The magnitude and significance varied according to the different stages of the reform process across the institutions and departments. Dramatic reductions in achievement gaps have been observed on several campuses, especially for women, under-represented minorities, and first-generation students. Reports of decreased DFW (D grades, F grades, and withdrawals from a course) rates are common, as is increased student persistence and success in subsequent courses as measured by grade performance. Project sites also found improved performance on exams designed and sponsored by disciplinary societies to assess knowledge of core disciplinary concepts (i.e., concept inventories). Some campuses also have tracked the effects of instructional interventions on more general psychological factors, such as self-efficacy, metacognition, and student attitudes toward science (AAU, 2017a).

3.3 Project Site Data and Reporting

AAU created a variety of mechanisms to help forward and monitor the work of the project sites. AAU collected survey and metric data to develop baseline information to guide project sites, established a mechanism for measuring improvement in teaching and learning at the department and institutional levels, and helped project sites in measuring their progress (AAU, 2017a). In addition, project sites provided regular annual reflective reports and participated in site visits with AAU professional staff. The aggregate of this information was used by AAU to identify cross-cutting strategies (Coleman, 2019).

One cross-cutting strategy was central to the institutional level—developing productive working partnerships between academic departments and institutional units and structures dedicated to educational effectiveness. Today, AAU observes that many institutions have recognized the interdependence of support units and departments in improving teaching and learning. In this new light, institutions are elevating and reorganizing the traditional teaching center into a full division or more closely aligning it with university leadership, oftentimes to an Associate Provost responsible for teaching innovation or excellence, with a direct reporting line to the Provost. By expanding and more centrally locating these teaching responsibilities at higher levels within the university, the institution can make its expectations for teaching more explicit to academic units; provide the necessary scaffolding for individual faculty members who wish to incorporate evidence-based teaching approaches into their course(s); partner with departments on projects that promote student learning, create inclusive classrooms, and retain highly-qualified students; provide support to assess institutional improvement efforts in teaching and learning; and help to adjust practice and policies at multiple levels of the university. Lastly, these more visible and institution-wide units are better positioned to compete for extramural grant funds to facilitate course transformation, teaching development efforts, and cultural change across the institution.

4 Network Level: The AAU STEM Network

The AAU STEM Network includes all AAU member campuses. Institutions’ representation in the network is facilitated by a designated point of contact appointed by the Provost. Many of the points of contacts were successful reformers in STEM education and campus leaders with experience supporting innovations in STEM. Designating point of contacts for the network served to empower individuals with intrinsic motivation and a passion for creating change.

The network level allowed AAU to spread ideas beyond the project sites and engage the broader membership. The goal was to influence all AAU members to be “as excellent in teaching as research.”

From a systems approach, AAU created various structures, processes, and messaging that aimed to sustain the network beyond the life of the project sties (Kezar et al., 2019). The goal is for the network to be responsive to emerging challenges in the process of reforming undergraduate STEM education and continuously provide a forum to disseminate model practices and policies.

4.1 Networking Meetings

A strength of AAU is its convening power and ability to generate partnerships and collaborations across a variety of organizations. All convenings are structured to be synergistic with each other and have the intent to leverage more change across the system.

The Initiative holds biannual network meetings where points of contact and other member campus faculty and administrative leaders interact, discuss challenges and strategies for creating change, and contribute and build their knowledge about efforts to improve STEM education. Frequently these forums provide an opportunity to link AAU campuses that are doing similar work or addressing similar challenges. Network meetings also provide space to explore and consider funding opportunities.

A culminating event included 41 AAU member campuses and over 100 faculty members and administrative leaders participating in the STEM Network Conference on January 27–28, 2020. The conference was facilitated in an evidence-based, large introductory science class format. Topics of the sessions included creating inclusive and welcoming classroom environments; using evidence-based teaching strategies; data analysis and analytic tools that are aimed at ensuring introductory STEM courses are equitable; and practices to document, evaluate and reward teaching effectiveness. The event also featured a poster session highlighting the 24-campus mini-grant activities funded by Northrop Grumman. Finally, a dedicated session engaged participants on communicating the value of improvements to undergraduate education to the public that was informed by national survey data AAU is collecting.

AAU also convened teams of department chairs from member campuses in 2015 and 2018. During these workshops, AAU discussed the evidence about improved learning gains and retention in the major witnessed in classes using engaged and structured teaching methods. The chairs then engaged in discussions on topics such as creating inclusive and welcoming classroom environments, using data to inform and assess curricular innovations, introducing practices to evaluate and reward teaching effectiveness, and developing productive partnerships between academic departments and centers for teaching and learning. By engaging STEM department chairs in these critical teaching and learning issues AAU has worked to increase the magnitude and speed of change in the quality and effectiveness of undergraduate STEM education at research universities.

4.2 Messaging and Outreach to Constituent Groups

Another mechanism to support change within the overall AAU network was communication with key constituent groups, including presidents, provosts, and deans. Project sites, for example, presented several times to the AAU Chief Academic Officers. These presentations showcased progress across campuses as a result of a critical cross-cutting strategy and aimed to spur similar action on other campuses.

AAU also created a communications plan that sent regular messages out to AAU network members about STEM education issues ranging from grant opportunities, to new national STEM education reports, to workshops and professional development opportunities, to state and federal policy updates.

4.3 Sharing Best Practices

AAU created an opportunity for AAU STEM Network sites to submit the work they were conducting on undergraduate STEM reform to be put in a sourcebook on the website, to help communicate and educate about existing change efforts. In addition, leaders in undergraduate STEM reform at AAU campuses that were not funded as project sites were brought in as expert speakers for AAU-sponsored meetings and conferences to inform and educate others within the Initiative. AAU published a case studies document in 2016 (Improving Undergraduate STEM Education at Research Universities: A Collection of Case Studies) (Dolan et al.) that provided best practices for other AAU campuses as well as campuses nationally that included project sites as well as any AAU campus conducting STEM reform work. Resources and documents that come out of the AAU are noticed and used by leaders on campuses across the country and could reach audiences that STEM reformers typically do not reach (often faculty advocates) and get into the hands of AAU decision makers such as Provosts and Presidents (and beyond). These opportunities to share efforts across all AAU campuses created lasting conversations and connections well beyond the project sites.

5 National Level: Ecosystem for Higher Education STEM Reform

The third level at which the AAU worked is at the national level, shaping dialogue and policy around STEM reform. Change can be much more impactful if the lessons within a set of institutions are shared more broadly, particularly any tools or resources developed, but also the advocacy and ideas around the change more generally. Also, if organizations work collectively to have a shared impact, they are more likely to influence change, as we have seen in collective impact theories of change (Kania & Kramer, 2013). The various groups AAU helped create and empower during the Initiative helped to fuel national STEM reform, foster synergies among organizations and better coordinate their work to have a stronger and lasting impact on STEM reform, increase funding for reform, and generate greater visibility through media about improvements to undergraduate STEM education.

5.1 Partnerships with National STEM Reform Groups

One of AAU’s major areas of emphasis to impact the broader STEM-reform level was joining and helping to create partnerships with organizations and associations.

AAU joined and helped to support a coalition of national organizations aimed at improving undergraduate STEM education named “Coalition for Reform of Undergraduate STEM Education” (Coalition or CRUSE). Coalition members include the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Association of American Colleges and Universities, the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, the Association of American Community Colleges, and the National Research Council. As a group, the Coalition convened funders and foundations to discuss important funding priorities and directions related to undergraduate STEM education. This resulted in the development of a major report called Achieving Systemic Change—A Sourcebook for Advancing and Funding Undergraduate STEM Education (CRUSE, 2014).

The association also reached out to teaching and learning groups such as the Bayview Alliance, Cottrell Scholars, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Professors, the Center for Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning (CIRTL), and the Professional Organizational Development (POD) Network. These partners were frequently invited to meetings of the project teams and network. Correspondingly, project sites and points of contact attended meetings by these groups. AAU staff also took on leadership roles, sat on boards, and assumed positions on steering committees for the National Alliance for Broader Impacts, the National Higher Education and Workforce/Business Forum, and the Accelerating Systemic Change Network (ASCN) as well as many related National Science Foundation (NSF) project advisory boards. The result was the cross-fertilization of knowledge between the various networks and organizations.

In recognizing that some systems change extended beyond the scope of STEM or AAU member campuses, AAU partnered with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) Board on Science to co-sponsor and organize the Education Roundtable on Systemic Change in Undergraduate STEM Education, an expert meeting on innovations being advanced to more effectively evaluate teaching. A workshop report titled, Recognizing and Evaluating Science Teaching in Higher Education: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (NASEM, 2020) documented the issues around the recognition and evaluation of science teaching in higher education.

In addition, AAU in partnership with NSF hosted a workshop, Essential Questions and Measures: Assessing Institutional Transformation of Undergraduate STEM Education (Miller et al., 2019). The objective of the workshop was to identify key improvement indicators at multiple levels to assess the impact of and further leverage projects aimed at developing a culture and practice of evidence-based teaching in undergraduate STEM courses. The workshop engaged 50 leaders, researchers, and evaluators of efforts to transform STEM teaching and learning to think about how best to assess the impact of the institutional transformation track of NSF’s Improving Undergraduate STEM Education program and give guidance on how to improve future calls for proposals.

5.2 Federal Policy

In 2016, the America Innovation and Competitiveness Act was approved by Congress late in the session. AAU was successful at including language in the final bill that clarifies that NSF’s broader impacts can be achieved through in-class improvements in undergraduate teaching. Specifically, the language makes it clear that the adoption and usage by the NSF awardee of evidence-based and/or active and engaged teaching practices proven to increase persistence and to enhance undergraduate learning and understanding of core STEM concepts in disciplines relating to the PI’s NSF-funded research award should be recognized by NSF review panels as an acceptable form of meeting NSF broader impacts criteria.

5.3 Public Relations

AAU also had a robust public relations and media plan.AAU worked to create general media attention through news articles about STEM-reform efforts happening nationally, to place articles in major scientific journals like CBE—Life Sciences Education (Dennin et al., 2017) and Nature (Bradforth et al., 2015) to directly reach faculty members, and to attend national STEM-reform conferences to promote and direct attention to the Initiative. AAU regularly issued press releases about the progress of the Initiative. These media efforts not only brought attention to the Initiative’s reform work in general, but also generated internal validation and legitimacy of the eight project sites, leveraged further local change, and created a buzz among the broader network by making visible the work of reformers.

6 Conclusion: Synergizing the Levels of the System

The Initiative leveraged the interactions between the three levels to try to create and strengthen synergy. For example, speakers were generally brought in from AAU’s work at the broader national level to give plenary speeches at their meetings. Additionally, meetings connected project sites and members of the broader AAU network for dialogue and information sharing. The general efforts to create media attention at the national level for the campuses and network also appeared to be an important way to use national attention to leverage local change. Many examples above highlight the synergy they were able to create from various multifaceted strategies.

Systems change is rarely engaged broadly in society nor in higher education in particular. While research consistently shows the importance of a systems approach to change—and specifically large-scale changes—few leaders, institutions, or organizations engage this approach. Working at several levels of a system—institutional, network, and national—is even more unheard of. Being able to document the AAU’s intentional use of a systems approach is important to demonstrate how such an approach can be strategically leveraged. AAU learned much from this systems approach (Coleman, 2019), and in an examination of the Initiative learned some additional lessons on how to coordinate a systems approach in even deeper ways (Kezar, 2018b).

Ultimately, this ambitious project, which AAU has continued, sought to increase the importance and value of effective undergraduate STEM teaching in the nation’s leading research universities, and continues to promote the implementation of a systemic view of educational reform within academia to improve the quality of undergraduate education.

7 About the Authors

Adrianna Kezar is the Wilbur-Kieffer Endowed Professor, Rossier Dean’s Professor in Higher Education Leadership at the University of Southern California.

Emily Miller is the Associate Vice President for Policy at the Association of American Universities.

8 References

Association of American Universities. (n.d.). Scholarship. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/education-service/undergraduate-education/undergraduate-stem-education-initiative/resources/scholarship

Association of American Universities. (2013). Framework for systemic change in undergraduate STEM teaching and learning. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/STEM%20Scholarship/AAU_Framework.pdf

Association of American Universities. (2017a). Essential questions & data sources for continuous improvement of undergraduate STEM teaching and learning. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/essential-questions-data-sources-continuous-improvement-undergraduate-stem-teaching-and-learning

Association of American Universities. (2017b). Progress toward achieving systemic change: A five-year status report on the AAU Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/progress-toward-achieving-systemic-change

Austin, A.E. (2014). Barriers to change in higher education: Taking a systems approach to transforming undergraduate STEM education [white paper commissioned for Coalition for Reform of Undergraduate STEM Education]. Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Austin, A.E. (2011). Promoting evidence-based change in undergraduate science education. National Academies National Research Council Board on Science Education. http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_072578.pdf

Beach, A. L., Henderson, C., & Finkelstein, N. (2012). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM education. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 44(6), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2012.728955

Bradforth, S. E., Miller, E. R., Dichtel, W. R., Leibovich, A. K., Feig, A. L., Martin, D., Bjorkman, K. S., Schultz, Z. D., & Smith, T. L. (2015). University Learning: Improve undergraduate science education. Nature, 523(7560), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/523282a

Coalition for Reform of Undergraduate STEM Education. (2014). Achieving systemic change: A source-book for advancing and funding undergraduate STEM education (C. L. Fry, Ed.). Association of American Colleges and Universities. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/publications/E-PKALSourcebook.pdf

Coleman, M. S., Smith, T. L., & Miller, E. R. (2019). Catalysts for achieving sustained improvement in the quality of undergraduate STEM education. Dædalus, 148(4), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01759

Dennin, M., Schultz, Z. D., Feig, A., Finkelstein, N., Greenhoot, A. F., Hildreth, M., Leibovich, A. K., Martin, J. D., Moldwin, M. B., O’Dowd, D. K., Posey, L. A., Smith, T. L., & Miller, E. R. (2017). Aligning practice to policies: Changing the culture to recognize and reward teaching at research universities. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(4), es5. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-02-0032

Dolan, E. L., Lepage, G. P., Peacock, S. M., Simmons, E. H, Sweeder, R., & Wieman, C. (2016). Improving undergraduate STEM education at research universities: A collection of case studies. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/STEM%20Scholarship/RCSA2016.pdf

Gardner, G., Ridgway, J., Schussler, E., Miller, K., & Marbach-Ad., G. (this volume). “Research coordination networks to promote cross-institutional change: A case study of graduate student teaching professional development.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 10). Pressbooks.

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2013). Embracing emergence: How collective impact addresses complexity. Stanford Social Innovation Review. http://rhap.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Embracing_Emergence_PDF.pdf

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock potential in yourself and your organization. Harvard Business Press.

Kezar, A. (2018a). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Kezar, A. (2018b). Scaling improvement in STEM learning environments: The strategic role of a national organization. American Association of Universities. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED591360.pdf

Kezar, A., Miller, E., Bernstein-Serra, S., & Holcombe, E. (2019). The promise of a “network of networks” strategy to scale change: Lessons from the AAU STEM Initiative. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 51(2), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2019.1569973

Margherio, C., Doten-Snitker, K., Williams, J., Litzler, E., Andrijcic, E., & Mohan, S. (this volume). “Cultivating strategic partnerships to transform STEM education.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 12). Pressbooks.

Miller, E. R., Fairweather, J. S., Slakey, L., Smith, T., & King, T. (2017). Catalyzing institutional transformation: Insights from the AAU STEM Initiative. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 49(5), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2017.1366810

Miller, E. R., King, T., Austin, A. E., Smith, K. A., Roberts, J. R., & Pullin, M. J. (2019). Promoting transformation of undergraduate STEM education: Workshop summary report. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/STEM-Education-Initiative/Promoting-Transformation-Report.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Recognizing and evaluating science teaching in higher education: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25685

Smith, D. G. (2015). Diversity’s promise for higher education: Making it work. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Toma, J. D. (2010). Strategic management in Higher Education: Building organizational capacity. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Willis, C. D., Best, A., Riley, B., Herbert, C. P., Millar, J., & Howland, D. (2014). Systems thinking for transformational change in health. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 10(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426413X662815

Wojdak, J., Phelps-Durr, T., Gough, L., Atuobi, T., DeBoy, C., Moss, P., Sible, J., & Mouchrek, N. (this volume). “Learning together: Four institutions’ collective approach to building sustained inclusive excellence programs in STEM.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 11). Pressbooks.