3 Bringing an Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Framework to University Change Work

Stephen M. Biscotte and Najla Mouchrek

1 Look at the Bright Side of Higher Education Change

In higher education, the impetus for change is often the identification of a specific need, problem area, or area of under-performance. Examples include institutions recognizing that their retention rates for female students in STEM are too low; students from underrepresented groups appear underprepared for the rigors of calculus; or instructors lack pedagogical content knowledge to teach large introductory courses effectively. Interventions are designed and implemented to address these perceived deficits, which are too often identified as personal characteristics and limitations of specific groups (e.g. “those bad teachers” or “those unprepared students”). Instead, leaders could focus on growing, celebrating, and leveraging the strengths of the community involved. In this paper, the authors will introduce a strengths-based mindset utilized in community-development work, Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD), to the area of higher education change.

Throughout this paper, the authors use general education curriculum reform examples and prompts. However, readers can use their own higher education reform efforts as a practical context in which to consider this approach. This article follows the structure and participatory design nature of the workshop presented at the 2019 Transforming Institutions Conference hosted by the Accelerating Systemic Change Network (ASCN). Those in attendance were invited to consider their own goals for institutional change (such as increasing content alignment of 2-year and 4-year STEM programs or reforming pedagogy across introductory chemistry courses) and envision how the framework might guide their work.

Prompt 1: Your Introduction

Hi my name is __________. I’m from ___________ (institution). And I’m interested in changing ______________on my campus.

1.1 Higher Education Change is Complex

In her book, How Colleges Change, Kezar (2018) points to the many narrowly focused change models available. These models often fail to account for the nature of the change itself, the complexity of higher education structure, and the diverse contexts in which change happens. A leader equipped with one model for change (e.g. scientific management theory) will likely use this tool to drive each reform effort (e.g. introducing course-embedded experiential learning for all undergraduate students) as if it were the “proverbial nail.” This primarily top-down effort may work in some cases. However, without attending to the context of the change and the people involved, the change leaders may suffer significant setbacks in the process or conclude with only a short-term, superficial impact.

In addition, there is immense variation among the roles of those involved (e.g. adjunct instructors vs full professors), the structures in which each one operates (e.g. hierarchical organizational structure within student affairs vs loose coupling of instructors in a department), and the institutional mission each one pursues (e.g. comprehensive state university vs small liberal arts college). While leveraging technology to support student interaction in foundational STEM courses might prompt change at one institution, it might fail at another, due to lack of infrastructure for change, misconception of the nature of the problem in different contexts, or misalignment with the values and perspectives on learning.

In their review of the literature on reform in STEM undergraduate teaching, Henderson et al. (2010) conclude that some change approaches are more commonly used, even if the results are mixed at best. For example, it is quite common for change leaders to invest in a pilot cohort of champions to develop best practice tools and resources to then share with the greater community. Unfortunately, it is also quite common for these efforts to go no further than the pilot stage. Therefore, to achieve desired goals it is imperative that change leaders develop a thorough understanding of diverse change theories and a versatile toolbox of strategies to deploy as needed (Kezar, 2018). Our work echoes Pilgrim et al. (this volume) on the importance of not only understanding a range of theories of change, but also aligning those with goals within particular contexts. With this framework and knowledgebase, leaders can better recognize the scope and the type of change, avoid pitfalls resulting from a mismatch of the type of change and strategies utilized, and achieve lasting results.

1.2 Change Leaders are Busy and Changing a Culture is Hard

Prompt 2: Time to Completion

I was given _________ (length of time) to complete this reform. And my job includes doing ________________ that are NOT tied to this reform.

Kezar (2018) makes it clear that “one of the most significant challenges is that leaders tend to focus on interventions and programs but ignore the change process” (p. xiii). However, personnel are already quite busy doing various things to support students. Administrators participate in shared governance, support the curriculum and academic programs, manage the day-to-day operations of the institution, and report to external stakeholders like policymakers and accreditors. Instructors teach courses, advise students, participate in shared governance, and manage research and publications. Student affairs professionals support student growth and progress outside of the classroom, as well as partnerships in the classroom. With this level of complexity, uncertainty, and time needed for success, it is no wonder that change leaders often fall back onto timeworn strategies or ill-suited change theories that do not match the environment. Time for reform is a rare commodity.

In addition, the drive to “change the culture” is plagued by another fundamental problem: does the university even have a tangible culture (Silver, 2003), a set of institutional values and beliefs shared by its members, to be changed? Perhaps not. Alternative change models, such as the ABCD model proposed here, require we recognize the university as a networked community of individuals and groups with strengths, values, and subcultures. Here we align with Bangera et al. (this volume) about the importance of connecting and supporting adaptive and hierarchical networks with a wide range of stakeholders. If we consider that a higher education institution is a community (instead of an organization with a culture), we can find in the community development literature a framework that meets the needs of over-stretched professionals and also supports the deployment of a variety of change theories and strategies as needed within the complex cultural and organizational structure of the academy. We can let go of the notion that we need to change an institution’s “culture,” when a shared campus-wide culture may not even exist. Instead, we can focus on something more concrete, which is changing some practices and norms of the individuals that make up the institution’s community through leveraging the assets and strengths of those involved.

2 ABCD as a Framework for Facilitating Change in Higher Education

Prompt 3: Who are the stakeholders involved with and/or impacted by this topic or issue?

a) Academic units: ______________

b) Administrative units: ______________

c) Interest Groups: ______________

d) Student groups: ______________

e) Beyond campus organizations: ______________

Prompt 3 Example: In the context of General Education Reform

a) Academic units: All departments and colleges

b) Administrative units: Registrar’s Office, advising network, admissions, and recruiters

c) Interest Groups: Strategic planning taskforce

d) Student groups: Student Government Association, professional fraternities

e) Beyond campus organizations: State and regional accreditors, community college and state transfer committees

Asset-Based Community Development provides a strengths-based approach to growth and change (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993). It is a clear mindset shift and digestible framework, perfect for the busy change agent “on the go,” but is robust enough to allow for the deployment of rigorous theories of change as needed over an extended period of time to achieve lasting success. It is not a quick fix or “silver bullet.” ABCD is a guide to complex, long-term, bottom-up higher education reform efforts.

ABCD serves as a roadmap to relationship development and a celebration of every member’s contributions. The role of change agents is to identify community assets and strengths, rather than deficits and needs, and to provide opportunities for relationship-building and asset mobilization for ongoing reflection and improvement (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993). For lasting positive change, reformers must first recognize that every individual, association, and institution has assets to contribute to ongoing community development; these are not clients that need to “buy in,” but citizens ready to participate (Mathie & Cunningham, 2003).

Different versions of a growth-focused, asset-based perspective might be seen also in other works in this volume, like for example in Pilgrim et al. The centrality of developing strong relationships in change networks is highlighted also in the work of Bangera et al. (this volume).

Community workers are using the principles of ABCD to guide their work in localities around the world (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993). Good examples include: the Bagot Community, an aboriginal network situated in a suburb of Darwin, Australia (Ennis & West, 2013); the youth of Lhasa, Tibet looking to capitalize on their tourism assets (Wu & Pearce, 2013); and local groups in Ethiopia collaborating with various non-governmental organizations (Mathie & Peters, 2014).

Through an ABCD lens, a college or university can be framed as a community of individuals (students, faculty, staff, administration, and local town), associations (student government, faculty senate and committees, housing and residence life, community coalitions, and non-profit organizations), and institutions (academic colleges, dining and residence halls, administrative offices, town hall, and local parks) working toward common goals of student learning and growth. To avoid work being done in isolation, change leaders can do much to facilitate and support constructive collaboration by following the ABCD framework.

2.1 ABCD Contextualized for Higher Education Reform

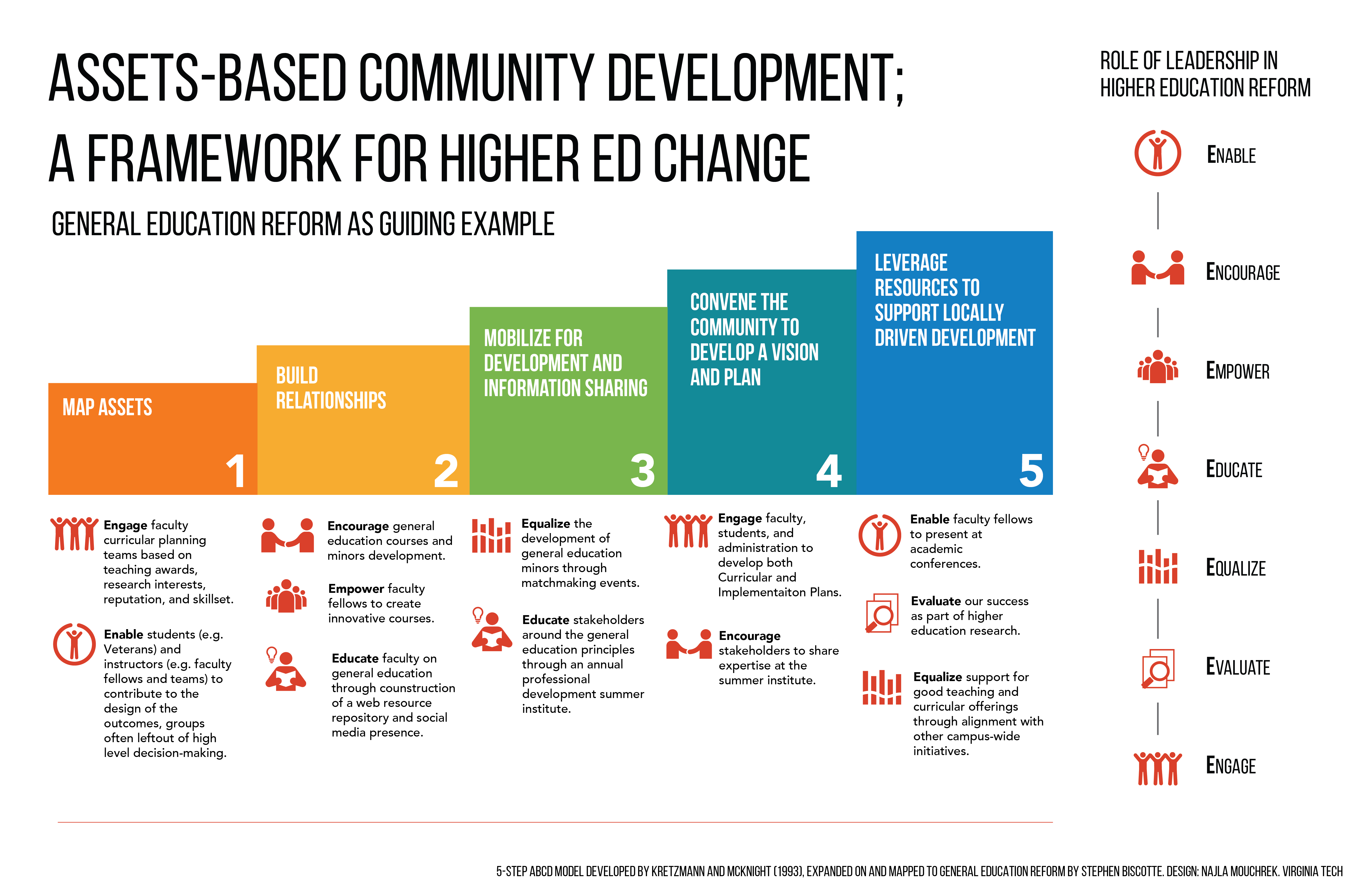

In Asset-Based Community Development (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993), change agents conduct the following five steps to incite positive change in a community: 1) map individual assets; 2) build relationships between community-members and stakeholders; 3) mobilize identified assets and share useful information among the constituencies, 4) bring the community together in ongoing discussion to develop a plan and mission for the future; and finally 5) leverage outside resources to support local initiatives.

In this article, Step 1 will be the focus as it is critical to laying a strong foundation on which to build the community development work and to shift the mindset of those involved. However, so that the reader can see the rest of the framework in action, in Figure 1 we provide the five steps of ABCD overlaid with potential strategies to guide the change agent and have included examples related to general education curriculum reform. For instance, within Step 1, change agents may engage curricular planning teams to develop new outcomes, while in Step 3, change agents may educate faculty and advisors on the general education website and resources.

2.2 Step 1: Mapping the Assets

Prompt 4: A purpose statement to get started

By _________ (end date), ________________ will be accomplished by _______________ (who involved) by doing ___________________ to address/achieve __________________ (problem/topic/issue at hand).

Prompt 4 Example: In the context of General Education Reform

By the end of one academic year, we will map the assets of the gen ed community to explore gen ed reform.

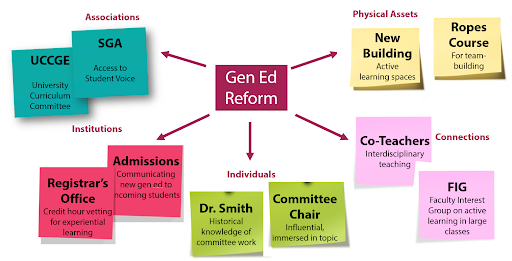

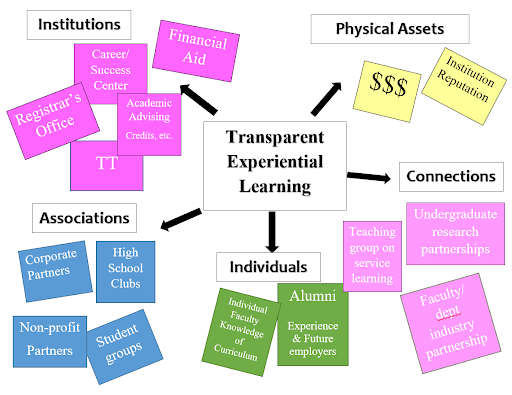

In a general education reform context, change agents would conduct an assets inventory to identify faculty with expertise in the general education outcome areas and a track record of high-quality teaching in foundational undergraduate courses. Reformers would identify administrative units, staff, committees, faculty interest groups, and student organizations with knowledge, experience, and a shared interest in achieving change. In addition, reformers could consider physical assets like new or innovative campus buildings or learning spaces. An assets inventory can help change agents to identify and celebrate local resources that are important to building an institutional foundation for lasting change.

Prompt 5: What are the assets on campus related to the following?

a) Physical: ____________________

b) Individual People: ___________________

c) Associations (unpaid): ________________

d) Institutions (paid): ___________________

e) Connections: ______________________

Prompt 5 Example: In the context of General Education Reform

a) Physical: New classroom building, ropes course

b) Individual People: “Dr. Smith” (a certain person with great historical knowledge or experience, the gen ed committee chair)

c) Associations (unpaid): Student government, gen ed curriculum committee

d) Institutions (paid): Offices of Registrar, Provost, or Admissions

e) Connections: Interdisciplinary team-teaching instructors, faculty study groups

An asset-map will look something like a more robust, “messy version” of the following examples from general education reform and experiential learning (from the workshop):

2.3 The Role of the Change Agent in ABCD

As facilitators of community development, the role of change agents is to “support networks that foster mutual learning and shared commitments so that people can work … together in relatively coherent and equitable communities” (Gilchrist, 2009, p. 21). According to the steps of ABCD (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993), community workers first map the university assets. Secondly, to help foster relationships among the community members that “promote respect, trust, and mutuality” (Gilchrist, 2009, p. 131) and go beyond superficial interactions, “meta-networking strategies” are employed. These strategies include: a) coordinating bi-weekly meetings and social engagements; b) helping develop structures that will support network sustainability; c) supporting member travel to conferences; and d) monitoring relevant networks to deal with tensions that can decouple a network bridge. This last responsibility is crucial to the health of the community.

If (when) there is ongoing conflict among community members, change agents ought to bring them in to help find common ground and “mediate, translate, and interpret between people and agencies that are not in direct or clear communication with one another” (Gilchrist, 2009, p. 116). Throughout the process, the change agent serves as a transformational leader and broker, developing trust while building and leveraging social capital (Purdue, 2011). The change-agent will wear the many hats of policymaker, event planner, and even conflict mediator to support the community development process.

At each stage of a higher education institutional reform effort, the change agent should strive to “expand the table” (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993) to comprise a far more inclusive and diverse membership to help ensure internal assets of our students, both undergraduate and graduate, faculty of all levels, community partners, and administration are not missed. “Robust and diverse community networks are vital for effective and inclusive empowerment because they encourage a wider range of people to become active citizens and enable those who do take on civic roles to perform their roles as community representatives and leaders” (Gilchrist, 2009, p. 17.) Another important aspect is that the exchanges in these community networks must be fundamentally participatory and iterative in nature (a point that is also made in this volume by Ngai et al.)

Despite the “turf wars” and financial and political debating, campus change efforts offer a common venue for community members to step outside of their titles and silos to participate in the democratic process, but only if provided the opportunity. Continuing with the general education reform example, by funding graduate assistants and including them in professional development opportunities and working groups, administration can provide opportunities for them to build social capital (e.g. NSF funding on CV, networking with full faculty) while gaining the expertise and voice to teach their peers and colleagues. Pre-tenured faculty belong at the table as well. As members of Faculty Learning Communities or Departmental Action Teams (as described elsewhere in this volume), these early career faculty can learn lessons and develop connections that can pay off in future committee appointments, scholarly collaborations, or tenure support. If reformers do not take these steps to “expand the table,” it is consequently difficult to identify (and later mobilize) the assets of these internal collaborators.

3 Conclusion

The ABCD framework has been used by the community development world for several decades. ABCD can provide busy higher education administrators and change agents the clear reframing they need to, as one workshop attendee put it, “see bridges rather than walls” that can so easily pop up throughout a reform process. It is a useful 5-step framework and strengths-based mindset to reorient higher education change theories and strategies (like the CODS or CACAO frameworks described elsewhere in this volume). Although there are proofs of concept from community development, empirical research across the higher education domain would be fruitful to measure the potential impact of this framework on higher education change.

“ABCD is not done to communities by ABCD experts” (Mathie & Cunningham, 2003, p. 484), just as reform is not accomplished in the university by faculty, administrators, or accreditation agencies. With guidance, change agents can leverage Step 1 of the framework to identify and map the assets of their own institution related to a given issue, a key foundation on which the rest of the reform effort can build. As one attendee at the workshop put it, “there are so many people impacted by a change that you really have to involve them from the beginning. The asset map reminds you that they exist and also have something to offer.” The change agent can then increase the opportunities for community building by a diverse and talented array of networked members. At the very least, this approach offers change agents the opportunity to re-envision their role as connection-makers and trust-builders rather than just “problem-solvers and fixers.”

4 Acknowledgments

This framework is guiding work supported by the NSF CCE STEM (ER2) grant #1737042.

5 About the Authors

Stephen Biscotte is the Director of General Education and an Instructor of Educational Psychology at Virginia Tech.

Najla Mouchrek is the Program Director for Interfaith Leadership and Holistic Development at Virginia Tech.

6 References

Bangera, G., Vermilyea, C., Reese, M., & Shaver, I. (this volume). “On the RISE: A case study of institutional transformation using idea flow as a change theory.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 5). Pressbooks.

Ennis, G., & West, D. (2013). Using social network analysis in community development practice and research: A case study. Community Development Journal, 48(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bss013

Gilchrist, A. (2009). The Well-Connected Community. The Policy Press.

Henderson, C., Finkelstein, N., & Beach, A. (2010). Beyond dissemination in college science teaching: An introduction to four core change strategies. Journal of College Science Teaching, 39(5), 18–25.

Kezar, A. J. (2018). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315121178

Kretzmann, J. P., & McKnight, J. L. (1993). Building communities from the inside out: A path towards finding and mobilizing community assets. ACTA Publications.

Mathie, A., & Cunningham, G. (2003). From clients to citizens: Asset-Based Community Development as a strategy for community-driven development. Development in Practice, 13(5), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/0961452032000125857

Mathie, A., & Peters, B. (2014). Joint (ad)ventures and (in)credible journeys evaluating innovation: Asset-based community development in Ethiopia. Development in Practice, 24(3), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2014.899560

Ngai, C., Corbo, J. C., Quan, G. M., Falkenberg, K., Geanious, C., Pawlak, A., Pilgrim, M. E., Reinholz, D. L., Smith, C., & Wise, S. (this volume). “Developing the Departmental Action Team theory of change.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 5). Pressbooks.

Pilgrim, M. E., McDonald, K. K., Offerdahl, E. G., Ryker, K., Shadle, S. E., Stone-Johnstone, A., & Walter, E. M. (this volume). “An exploratory study of what different theories can tell us about change.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 7). Pressbooks.

Purdue, D. (2001). Neighbourhood governance: Leadership, trust and social capital. Urban Studies, 38(12), 2211–2224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120087135

Silver, H. (2003). Does a university have a culture? Studies in Higher Education, 28(2), 157–169. https://10.1080/0307507032000058118

Wu, M. Y., & Pearce, P. L. (2013). Asset-Based Community Development as applied to tourism in Tibet. Tourism Geographies, 16(3), 438–456. https://10.1080/14616688.2013.824502