13 Transforming Teaching Evaluation in Disciplines: A Model and Case Study of Departmental Change

Sarah E. Andrews, Jessica Keating, Joel C. Corbo, Mark Gammon, Daniel L. Reinholz, and Noah Finkelstein

Current teaching evaluation systems for merit, reappointment, tenure, and promotion decisions in higher education, particularly at research institutions, often poorly measure teaching effectiveness (Bradforth et al., 2015) and lack systematic processes for reflection and formative development of teaching quality. These systems typically over-rely on end-of-semester student evaluations (SETs), which have been shown to be susceptible to bias (Huston, 2006; Li & Benton, 2017; MacNell et al., 2015; Youmans & Jee, 2007). They can also be inconsistent within and across departments for a given institution, making it particularly difficult to track change over time. In response to these concerns and national calls for improvement to teaching quality (e.g., National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2018; President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 2012; Seymour & Hewitt, 1997), the Teaching Quality Framework Initiative (TQF) is creating a process and tools for systemic transformation of departmental evaluation of teaching at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU-B).

As part of the multi-institutional TEval project (Finkelstein et al., this volume), the TQF is grounded in the scholarship of higher education (e.g., Bernstein, 2002; Bernstein et al., 2010; Glassick et al., 1997), institutional and organizational change in academic contexts (e.g., Corbo et al., 2016; Elrod & Kezar, 2017; Kezar, 2013; Reinholz et al., 2017; see also Kezar & Miller, this volume), and scholarly approaches to teaching and learning (e.g., Beach et al., 2016; Boyer, 1990; Fairweather, 2002). We focus on evaluation of teaching as this can directly impact long-term objectives of institutions of higher education, including increased valuation of teaching, externalization of departmental and institutional expectations about teaching and learning, improved instruction and student outcomes, a systematic approach to broadening diversity and inclusion, and a shift in culture toward a scholarly approach to teaching. TQF objectives span across multiple scales and include, but are not limited to: 1) aligning and sharing resources, processes, and values across departments, 2) identifying evidence-based measures of teaching quality and adapting to department needs, 3) adopting these quality measures campus-wide, 4) helping departments and the university establish guidelines for what teaching excellence means for merit, reappointment, tenure, and promotion (contextualized to department), 5) enhancing the visibility and value of teaching campus-wide, 6) supporting a national movement to value educational practices, and 7) influencing policy and value-setters (e.g., the Association of American Universities [AAU]).

In this chapter, we briefly present the overall framework for change and the structure of TQF activities, explore the departmental layer of change in detail by presenting a three-phase process (cultivating interest, forming departmental teams, facilitating regular departmental team meetings), and then describe a case study of one department that has engaged in all three phases. The TQF Initiative currently (May 2020) supports 19 units (11 STEM, eight non-STEM) across three colleges (Arts & Sciences, Engineering & Applied Sciences, and Business) at CU-B: eight in Phase 1, three in Phase 2, and eight in Phase 3. We complement the three-phase process (where departmental level change happens) with regular stakeholder meetings, outreach to key administrative officials, and the sharing of resources and ideas across departments to create campus-wide change. We anticipate the tools and approaches that we describe in this chapter will be of interest and use to multiple stakeholders, particularly policy makers, education researchers, and change agents.

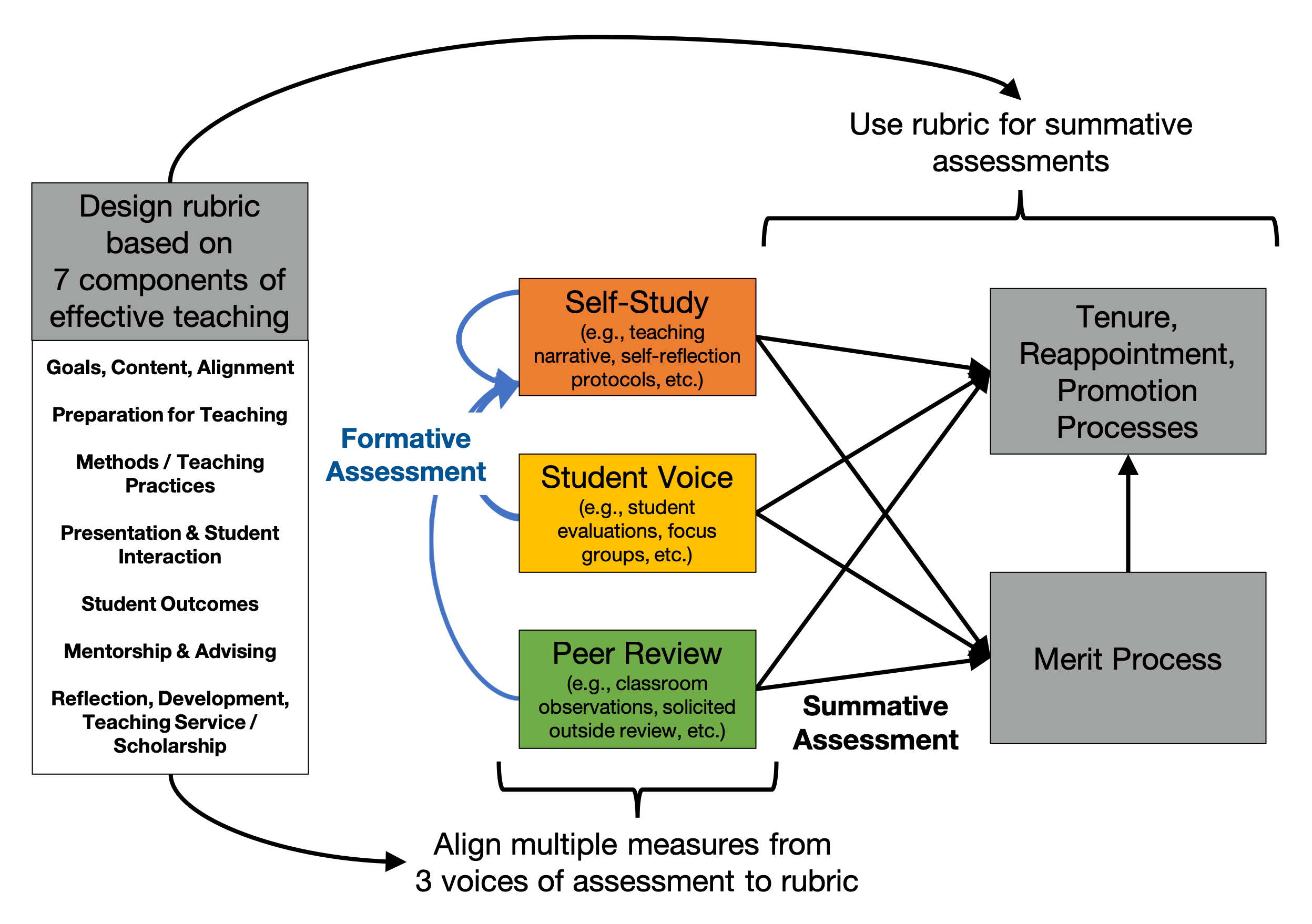

1 TQF Framework model

The TQF Initiative framework model for improved teaching evaluation is based on several components: a rubric grounded in scholarship around higher education, teaching and learning, and teaching evaluation; the use of multiple measures from multiple voices (the faculty member being evaluated, their peers, and students); explicit attention to formative as well as summative assessment practices; the alignment of the rubric with the multiple measures/voices, and the use of the rubric in summative evaluations for merit, reappointment, tenure, and promotion (Figure 1). The TQF assessment rubric was developed from foundational scholarship (Boyer, 1990; Glassick et al., 1997) and work at the University of Kansas (Greenhoot et al., 2017). An early structure was based around six components of scholarly activity relevant to teaching (adapted from Glassick et al., 1997), but based on feedback from early TQF participants these were revised to the current seven dimensions of teaching effectiveness: 1) goals, content, and alignment, 2) preparation for teaching, 3) methods and teaching practices, 4) presentation and student interaction, 5) student outcomes, 6) mentorship and advising, and 7) reflection, development, and teaching service/scholarship. The full TQF assessment rubric can be found at: https://www.colorado.edu/teaching-quality-framework/TQF_Assessment_Rubric.

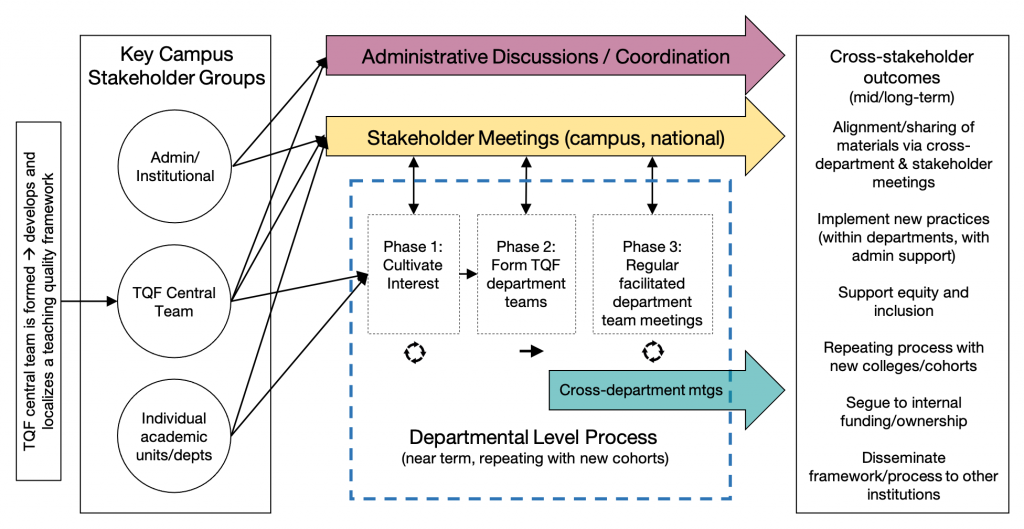

2 Structure of TQF activities

The TQF central team serves as a hub of resources, scholarship, and personnel, in communication and collaboration with individual academic units and administrators (Figure 2). TQF central members are broadly trained in STEM education, disciplinary-based education research, social psychology, information technology, higher education, and/or institutional/organizational change. In particular, facilitators are postdoctoral level research associates who are hired for their experience and skills in facilitation, project management, qualitative research, and program assessment. These skills are also developed on the job via training, shadowing, and co-facilitating with experienced facilitators (see Chasteen et al., 2015 and Reinholz et al., 2017 for similar examples of postdoctoral level researchers as facilitators).

At the center of the change process is support of departments through a three-phase departmental level process (encompassed by the dashed blue lines in Figure 2) that culminates in Departmental Action Team (DAT) working groups (hereafter, TQF departmental teams). This new type of approach to faculty and departmental development uses externally-facilitated faculty teams to support sustainable departmental change by shifting departmental structures and culture (Corbo et al., 2016; Reinholz et al., 2017; also see Ngai et al. [this volume] for more on the DAT model and theory of change). TQF departmental teams are described further in Figure 3 and Sections 3 and 4 below. Regular campus meetings (one per semester) and annual national meetings with other institutions in the TEval project serve multiple purposes, including bringing together stakeholders from multiple levels (e.g., faculty, staff, and administrators), voicing support from administrators, and showcasing successes and new resources (e.g., the TQF FAQ and departmentally-defined measures). Sharing of resources in particular provides a means of facilitating common structures and language across departments, campus-wide, and cross-institutionally. Additionally, these meetings, along with cross-departmental meetings of faculty from Phase 3 departmental teams, help to build community and maintain engagement in the project by providing regular opportunities for stakeholders to converse with others working towards a common goal (improved teaching evaluation), and who are often grappling with similar challenges. It is not uncommon to hear from participants that they value knowing that they are not alone in the process. Finally, regular strategic meetings between TQF central and key administrative/institutional level stakeholders help sanction and garner support for the project and coordinate efforts campus wide (Margherio et al. [this volume] also describes example processes for building shared vision).

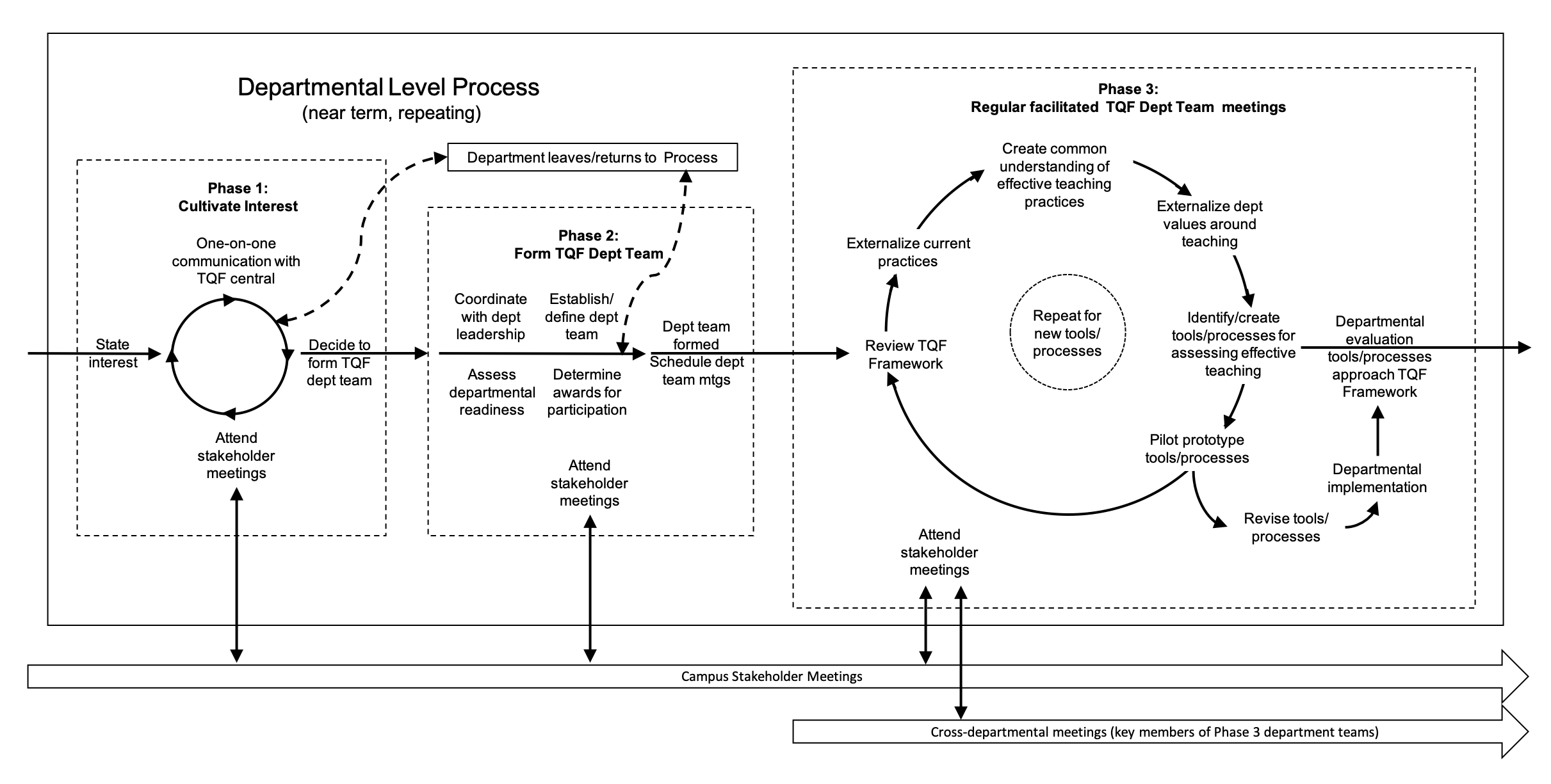

3 TQF Three-Phase Departmental Process Model

The TQF initiative focuses on departments as the key unit of sustained change (see Marbach-Ad et al. [this volume] for another example of a departmental-level approach to change and theoretical background on departments as a key unit of change). The TQF three-phase departmental process includes: 1) cultivating interest, 2) forming departmentally based change teams, and finally 3) facilitating the working teams to design and enact the change.

3.1 Phase 1: Cultivating interest

In Phase 1 (Figure 3, left panel), departments express interest, which is cultivated via one-on-one meetings with TQF central members and attendance at regular campus-wide stakeholder discussions. Cultivating interest also involves awareness raising within a department, building on prior educational change efforts, and responding to external pressures and internal concerns (expanded upon in Table 1). Units may stay in Phase 1 for extended periods depending on: a) unit-level interest/support for active engagement (e.g., see characteristics that define department readiness for change, after Elrod & Kezar, 2017, in Table 2) and b) TQF central resources (e.g., time, personnel).

| Mode of Cultivating Interest | Description/Examples |

| Direct discussions with leadership | One-on-one meetings between TQF central member(s) and campus/ department leadership to raise awareness of the project, discuss how TQF efforts may connect with campus/department efforts/goals, and address questions they may have related to the TQF Initiative. |

| Awareness raising via stakeholder meetings | Once per semester, TQF central organizes meetings for faculty from Phase 1, 2, and 3 units, key administrators, and other stakeholders such as students and representatives from units with overlapping goals (e.g., the Boulder Faculty Assembly, Office of Information Technology, Center for Teaching and Learning, Institutional Research, etc.). Typical meetings include TQF updates on the local and national status of the project (e.g., showcasing successes), guided discussions around a theme (e.g., student evaluations of teaching), and share-outs from Phase 3 units on tools and processes they have developed. |

| Awareness raising within a department | The TQF PI and/or a postdoctoral research associate give a brief presentation, typically during a faculty meeting. The presentation includes an overview of the framework (e.g., Figure 1), status/progress of the project as a whole and examples from other departments, and an explanation of what would be involved if they opt-in to forming a departmental team (e.g., a simplified explanation of Phases 2 and 3 from Figure 3). Faculty are then given the opportunity to ask questions, express concerns, share about related work they are doing in the department, etc. |

| Building on prior educational change efforts | In some cases, there are existing efforts within a department that overlap with or align with teaching evaluation in some way (e.g., efforts to create department-wide learning goals, implement evidence-based teaching practices, form teaching circles of peers who observe each other and meet collectively to discuss/share feedback, etc.). In such cases, the TQF central team works to show how TQF department teams could work with and build upon those efforts, rather than replace those efforts (e.g., build recognition for using departmental learning goals and/or evidence-based practices into departmental evaluation of teaching). |

| Responding to external pressures and internal concerns | External pressures such as accreditation or internal concerns such as dissatisfaction with one or more aspects of their current teaching evaluation practices (e.g., over-reliance on student evaluations of teaching, a lack of transparency in the annual merit evaluation process, perceived lack of value for quality teaching, etc.), can lead to a desire to improve departmental teaching evaluation practices. However, many departments lack knowledge on how to approach making such changes. TQF can respond to these concerns by providing a facilitator with a depth of expertise on teaching evaluation and institutional change, by brokering connections with key administrators, and by connecting them to other departments engaged in the work. |

| Characteristics Defining Readiness |

| Awareness of a need (by individual or groups of faculty and/or department leadership) within their department for improved evaluation of teaching |

| Interest and motivation as expressed by faculty and/or department chair |

| Consensus or critical mass (some significant proportion, yet to be defined, of the department must be aware of the need for change and be motivated enough to support the formation of a team and be open to making changes to their evaluation systems) |

| Commitment from department leadership (e.g., the chair, associate chair, and/or relevant committees) |

| Bandwidth and resources for enacting change (e.g., 3–6 department members are able to form a team and have time to meet regularly enough to drive progress, approximately twice per month) |

| Department culture that functions well in terms of internal communication and pathways toward change and sustaining the change efforts after TQF involvement |

3.2 Phase 2: Forming a TQF departmental team

During Phase 2 (Figure 3, center panel), the TQF central team and departmental leadership coordinate to define timelines, processes, and members for the TQF departmental team using an opt-in model: departments choose to participate and determine who participates and how participants will be rewarded. While the formation of a team is typically left to the department to determine, TQF central members share and encourage the design of ideal characteristics of a team (Table 3). Methods by which TQF departmental teams have formed and/or team members have been recruited are included in Table 4. Incentives for participation are also determined primarily by the department; TQF central members share a few options on how they might provide incentive for participation (e.g., pay, service credit, or course release) and then let departments take the lead. Phase 2 can occur over a short time period (e.g., weeks) or may extend over longer periods depending primarily on the length of time it takes departments to recruit team members and determine incentive structures.

| Characteristics | Additional Explanation/Notes |

| Ensure representation from different voices within the department | What this means may vary by department, but some examples include representation across ranks (instructor, tenure-track, tenured), demographic variability (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, time in department), and representation from people who teach different course types (e.g., lower division versus graduate, online versus in-class or hybrid, language learning versus culture, lecture versus lab, etc.). |

| Secure one or more department members who are well placed with power and status within the department | People who may be initially skeptical of changing teaching evaluation practices but who could be brought on board can be quite powerful in terms of helping to change minds in the department. However, people who are immovably skeptical and uncompromising can inhibit efforts and should be avoided. |

| Where possible, select members who are well placed within department structures that are related to teaching evaluation | Examples include associate chairs, chairs, personnel committee members, peer evaluation committee members, etc. |

| Include several people who are enthusiastic and care deeply about teaching | The team should not be made up exclusively by such people, as in some departments there can be stigma associated with a heavy focus on teaching and they may experience trouble getting recommendations from the team accepted in the broader department. Ideal candidates are those who both care deeply about teaching/pedagogy and who are well respected in the department. |

| The team should be made up of people who are comfortable working with each other | Examples include department members who have a reputation as team players and/or who have a history of working well together (e.g., have worked on other committees successfully), etc. |

| Methods Used by Departments to Form TQF Departmental Teams |

| Formation out of existing committees or structures (e.g., a Faculty Learning Community [FLC] or an Undergraduate Studies Committee)

A department-wide call for volunteers, taking whoever was interested (attending to characteristics in Table 2 where possible) Assignment to the team by the department chair Individual recruiting by the department lead (i.e., the person coordinating with TQF central) Some combination of the above (e.g., a department-wide call followed by assignment by a chair or recruiting additional members to an existing committee or structure) |

3.3 Phase 3: Regular Facilitated TQF Departmental Team Meetings

In Phase 3 (Figure 3, right panel), TQF departmental teams engage in regular, facilitated meetings to align their teaching evaluation practices with the TQF framework. They typically begin by reviewing the framework (e.g., Figure 1 and the TQF assessment rubric) to ensure they understand the context and goals they are working toward. Facilitators use probing questions to help faculty externalize their current teaching evaluation practices (e.g., “Can you describe how your department currently determines annual merit? Is this process written down? How often does it change?”), and areas of common concern (e.g., “Is there a particular part of the merit process that causes tension in your department?”). Having them share about common teaching practices in their department and the extent to which they are already engaging in and encouraging the use of evidence-based practices can help faculty start to externalize department values around teaching. As teams select an aspect of their teaching evaluation system to improve and begin working on adapting existing tools and processes, they continue to explicate their values around teaching as they make decisions on the structure and content of these tools/processes. For example, many teams start by focusing on peer observation with the goal of developing a structured protocol for observations. As faculty review existing protocols and make choices about which one(s) they prefer and adapt the content to their discipline, they continuously engage in conversations about teaching practices in their department and the degree to which they believe they could achieve department buy-in to the content and form of the protocol and procedures for its use. Once a team has completed a draft of a particular tool/process, they typically move towards departmental implementation of the tool/process outside of team meetings (touching base in meetings as needed to facilitate implementation) and move on to a new tool/process during team meetings. In other words, they typically take a piecemeal, iterative approach rather than developing a completely revised system before seeking departmental approval. The processes for gaining approval for departmental implementation vary somewhat by department and are still being studied, but in general involve: 1) sharing the tool/process with representatives from relevant committees and other key members of the department (as defined by the team members), 2) revisions as needed, 3) sharing the revised tool/process department wide for more extensive review and feedback (e.g., via sending an email to the entire department and/or discussing in a department-wide meeting), 4) additional revisions as needed, and 5) a departmental vote on whether to adopt the new tool/process.

The TQF Initiative has supported three cohorts engaged in Phase 3. The two units in Cohort 2 (one STEM, one non-STEM) are special cases in that they have engaged in the process but have had only minimal facilitation by the TQF central team; they are closer to a consultation model that we have not finished defining and are thus out of the scope of this chapter. The other six Phase 3 departments are split evenly between Cohort 1 (all STEM) and Cohort 3 (all non-STEM). While Cohorts 1 and 3 are separated in time (Cohort 1 started in Fall 2017/Spring 2018 and Cohort 3 started in Fall 2018/Spring 2019), the defining characteristics of the cohorts are similarity in structure, process, activities engaged in, and resources available to the TQF departmental team when it commenced. Cohort 1 spent more time early on reviewing the TQF framework, externalizing current practices, and creating common understanding of effective teaching practices, and thus spent a significant amount of time on more abstract discussions. As a result, they made less early progress toward achieving concrete goals (e.g., revisions to their current teaching evaluation practices). The TQF facilitators started to make progress toward such goals when they assembled a wide array of peer observation protocols and showed the TQF departmental teams the landscape of possibilities for such data sources.

The TQF departmental teams entering Cohort 3 benefitted from starting later in the Initiative, as the TQF departmental team process was modified based on facilitator experiences with Cohort 1. In particular, TQF facilitators modified their approach to move more quickly to working on concrete goals by, for example, identifying an aspect of their current teaching evaluation that they believed could be improved, identifying the range of possible tools already available, selecting the one that best fit their needs, and modifying as needed. Other aspects of the Phase 3 cycle, such as reviewing the framework and creating a common understanding of teaching excellence were touched upon early but were then revisited as needed throughout; working on a specific tool/process placed these more abstract conversations in a concrete context and so their discussions could be more productive and efficient. Cohort 1 is now following a similar process to Cohort 3 (e.g., working on concrete goals and cycling back to the framework or other aspects as needed).

All eight of the Phase 3 departments/units have developed new or revised tools and processes for teaching evaluation, including protocols for peer observation, self-reflection, student rating systems, and classroom interviews. Many of these tools and processes are now publicly available on the TQF website (TQF Initiative, n.d.).

4 A Case Study of the TQF Three-Phase Departmental Process: The Juniper Department

The Juniper department (fictitious name) is a humanities department in the College of Arts & Sciences at CU-B.

4.1.1 Juniper Department Phase 1

In October 2017, a faculty member contacted the TQF central team: she was on the department’s committee responsible for reviewing materials for annual merit and had been tasked with proposing an alternative teaching evaluation method for their merit process. Between this first contact and April 2018, she, along with the two other members of the committee, one of whom was the department chair, met with TQF team member Keating several times, and at the end of April, they held a listening session during one of their department-wide meetings. Through these meetings, it became clear that the Juniper department was ready for change. They had consensus that their current system of teaching evaluation for merit was problematic and were particularly dissatisfied with the heavy weight given to the omnibus questions on the SETs (e.g., “rate your instructor overall” and “rate the course overall”), particularly due to concerns about bias. But they lacked the expertise and time to survey the landscape of research and come up with alternatives to their system. In the spring, TQF central did not have the capacity to take on an additional departmental team, but it was decided that they could begin in Fall 2018.

4.1.2 Juniper Department Phase 2

Phase 2 occurred during the summer of 2018. The three people who initially approached TQF in Phase 1 became the first Juniper TQF departmental team members (one was assigned the role of team lead, i.e., the person coordinating with TQF central) and an additional two faculty were recruited via a department-wide call for volunteers. The five members of the Juniper team included three instructors, one associate professor, and one full professor (who is also the department chair), four of whom were women and one of whom was a man. Incentives for participation were determined internally by the department and are unknown at this time but at minimum were counted as a service assignment. In late August 2018, a member of the Juniper team attended the Fall 2018 stakeholders’ meeting and the Juniper team and TQF central scheduled meetings for the coming term.

4.1.3 Juniper Department Phase 3

The Juniper Department began regular TQF facilitated team meetings (approximately two per month) in the fall of 2018. They were part of Cohort 3 and benefited from TQFs experiences working with Cohort 1 (as described in section 3.3 above). Two TQF facilitators (postdoctoral-level scholars Andrews and Keating) intentionally focused the departmental team as quickly as possible on beginning the work of revising specific tools and processes. In the first meeting, they were re-introduced to the TQF project and framework model (Figure 1) and engaged in a facilitated discussion around their current teaching evaluation practices and potential areas they felt most needed addressing. By the second meeting, they were already reviewing the landscape of peer-observation protocols and beginning the work of selecting a protocol that best fit their needs (the UTeach Observation Protocol [UTOP]; Walkington & Marder, 2014; Wasserman & Walkington, 2014) and modifying it to reflect their discipline and teaching values. By the end of their first semester of facilitated meetings, they were able to bring a peer-observation protocol and procedures for their use to their department as a whole, and in early Spring 2019, the Juniper department voted to implement these in Fall 2019.

Also in Spring 2019, the first several Juniper team meetings delved back into the framework and discussions around their current merit system. In particular, they reviewed their system with an eye toward alignment with the framework. They then spent several meetings alternating between working on a guide for incorporating self-reflection into their merit system, and a teaching evaluation rubric (based on the TQF assessment rubric) to evaluate multiple measures from multiple voices (self-reflection, peer observation, SETs, and course materials) for annual merit. Members of the Juniper team also attended the TQF stakeholders’ meeting and the inaugural cross-departmental team meeting (one to two members from each Phase 3 department team) in the spring of 2019.

In late spring 2019, the Juniper team members brought their self-reflection guide and merit evaluation plan to the rest of the department for a vote, which was successful: the new system, which includes revised tools and approaches for peer review, self-reflection, and student ratings, was used in Spring 2020 to evaluate materials from the 2019 calendar year. Currently (May 2020), the Juniper department is still engaged with TQF with plans to connect as needed to aid implementation of their new tools and processes and to consider ways they may help their faculty prepare materials for the new system.

5 Ongoing Efforts and Future Steps

The TQF continues to gain momentum as a fourth cohort of five departments within a single college will be entering Phase 3 starting in Fall 2020. Cohort 4 will be similar to Cohort 3 in most aspects but will include structures (e.g., college-level cross-department team meetings) to foster collaboration and facilitate alignment of teaching evaluation structures within the single college. Other departments (e.g., the Juniper department described above) are reaching a point where they are transitioning from the TQF facilitated departmental teams of Phase 3 to a consulting model (in the process of being defined, but generally, TQF central will provide support as needed) with different needs/goals. We are reaching a point where TQF central resources are being outpaced by the increased level of interest in engaging with the process and so are: 1) developing a toolkit that can be used by interested departments in the absence of a TQF facilitator (but with consultation), and 2) exploring mechanisms to institutionalize the project. We are also actively connecting with other units of the TEval coalition (University of Massachusetts Amherst and the University of Kansas), and the BayView Alliance, NSEC, and NASEM efforts in teaching evaluations.

6 Acknowledgements

We are grateful to a department team member participant from the “Juniper” Department for their review of this paper. Comments from four anonymous reviewers also greatly improved this paper. We are also grateful for the support of the NSF (grant DUE-1725959), the TEval coalition, the Bayview Alliance, the AAU, CU-B College of Arts and Sciences, College of Engineering & Applied Science, and Leeds School of Business. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of these funders.

7 About the Authors

Sarah Andrews is a Research Associate in the Center for STEM Learning at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Jessica Keating is an Assessment Analyst in the Office of Data Analytics (ODA) and collaborator/former postdoctoral researcher for the Teaching Quality Framework (TQF/TEval) at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Joel C. Corbo is a Senior Research Associate in the Center for STEM Learning at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Mark Gammon is a sociologist and Learning Development & Design Manager in the Office of Information Technology at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Daniel Reinholz is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at San Diego State University.

Noah Finkelstein is a Professor in the Department of Physics and co-Director of the Center for STEM Learning at the University of Colorado Boulder.

7 References

Beach, A. L., Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., & Rivard, J. K. (2016). Faculty development in the age of evidence: Current practices, future imperatives. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Bernstein, D. (2002). Representing the intellectual work in teaching through peer-reviewed course portfolios. In S. F. Davis & W. Buskist (Eds.), The teaching of psychology: Essays in honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie and Charles L. Brewer (pp. 215–229). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. http://hdl.handle.net/1808/7987

Bernstein, D. J., Addison, W., Altman, C., Hollister, D., Komarraju, M., Prieto, L., Rocheleau, C., & Shore, C. M. (2010). Toward a scientist-educator model of teaching psychology. In D. F. Halpern (Ed.), Undergraduate education in psychology: A blueprint for the future of the discipline (pp. 29–45). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12063-002

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. The Carnegie

Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Bradforth, S. E., Miller, E. R., Dichtel, W. R., Leibovich, A. K., Feig, A. L., Martin, J. D., Bjorkman, K. S., Schultz, Z. D., & Smith, T. L. (2015). University learning: Improve undergraduate science education. Nature, 532(7560), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/523282a

Chasteen, S. V., Perkins, K. K., Code, W. J., & Wieman, C. E. (2015). The Science Education Initiative: An Experiment in Scaling Up Educational Improvements in a Research University. In G. C. Weaver, W. D. Burgess, A. L. Childress, & L. Slakey (Eds), Transforming institutions: Undergraduate STEM education for the 21st Century (pp. 125–139). Perdue University Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296705160_The_Science_Education_Initiative_An_Experiment_in_Scaling_Up_Educational_Improvements_in_a_Research_University

Corbo, J. C., Reinholz, D. L., Dancy, M. H., Deetz, S., & Finkelstein, N. (2016). Sustainable change: A framework for transforming departmental culture to support educational innovation. Physical Review Special Topics: Physics Education Research 12, 010113. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.010113

Elrod, S., & Kezar, A. (2017). Increasing Student Success in STEM: Summary of A Guide to Systemic Institutional Change. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 49(4), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2017.1357097

Fairweather, J. (2002). The ultimate faculty evaluation: Promotion and tenure decisions. New Directions for Institutional Research, 114, 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.50

Finkelstein, N., Greenhoot, A. F., Weaver, G., & Austin, A. E. (this volume). A department-level cultural change project: Transforming the evaluation of teaching. In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 14). Pressbooks.

Greenhoot, A. F., Ward, D., & Bernstein, D. (2017). Benchmarks for teaching effectiveness rubric. The University of Kansas Center for Teaching Excellence. https://cte.ku.edu/rubric-department-evaluation-faculty-teaching

Glassick, C. E., Huber, M. T., & Maeroff, G. I. (1997). Scholarship assessed: Evaluation of the professoriate. Special Report. Jossey Bass Inc.

Huston, T. A. (2006). Race and gender bias in higher education: Could faculty course evaluations impede further progress toward parity? Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 4(2), article 34. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol4/iss2/34

Kezar, A. (2013). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change. Routledge

Kezar, A., & Miller, E. R. (this volume). “Using a systems approach to change: Examining the AAU Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 9). Pressbooks.

Li, D., & Benton, S. L. (2017). The effects of instructor gender and discipline group on student ratings of instruction. IDEA Research Report #10. The IDEA Center. https://www.ideaedu.org/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/Research%20Reports/Research_Report_10.pdf

MacNell, L, Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A. N. (2015). What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 40(4), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9313-4

Marbach-Ad., G., Hunt, C., & Thompson, K. V. (this volume). “Using data on student values and experiences to engage faculty members in discussions on improving teaching.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 8). Pressbooks.

Margherio, C., Doten-Snitker, K., Williams, J., Litzler, E., Andrijcic, E., & Mohan, S. (this volume). “Cultivating strategic partnerships to transform STEM education.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 12). Pressbooks.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018). Indicators for monitoring undergraduate STEM education. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24943

President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. (2012). Engage to excel: Producing one million additional college graduates with degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED541511.pdf

Reinholz, D. L., Corbo, J. C., Dancy, M., & Finkelstein, N. (2017). Departmental Action Teams: Supporting faculty learning through departmental change. Learning Communities Journal, 9, 5–32. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327634179_Departmental_Action_Teams_Supporting_Faculty_Learning_Through_Departmental_Change

Seymour, E., & Hewitt, N. M. (1997). Talking about leaving: Why undergraduates leave the sciences. Westview Press.

Teaching Quality Framework Initiative. (n.d.). Teaching Quality Framework Initiative. University of Colorado Boulder. https://www.colorado.edu/teaching-quality-framework/tools-for-teaching-evaluation

Walkington, C., & Marder, M. (2014). Classroom observation and value-added models give complementary information about quality of mathematics teaching. In T. Kane, K. Kerr, & R. Pianta (Eds.), Designing teacher evaluation systems: New guidance from the Measuring Effective Teaching project (pp. 234–277). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119210856.ch8

Wasserman, N., & Walkington, C. (2014). Exploring links between beginning UTeachers’ beliefs and observed classroom practices. Teacher Education & Practice, 27(2/3), 376–401. https://www.tc.columbia.edu/faculty/nhw2108/faculty-profile/files/TEP27(2_3)_Wasserman.pdf

Youmans, R. J., & Jee, B. D. (2007). Fudging the numbers: Distributing chocolate influences student evaluations of an undergraduate course. Teaching of Psychology, 34(4), 245–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280701700318