17 Making Teaching Matter More: REFLECT at the University of Portland

Stephanie Salomone, Heather Dillon, Tara Prestholdt, Valerie Peterson, Carolyn James, and Eric Anctil

1 Introduction

Four of us sat at a round table at the WIDER PERSIST conference in Boise, Idaho in April 2016 and scribbled ideas furiously on colored post-it notes. Our charge was to create a vision statement that reflected the teaching and learning outcomes that we would most like to see on our home campus. Twenty minutes later, we had the following, which guided our team to create the REFLECT program, Redesigning Education for Learning through Evidence and Collaborative Teaching:

We spent the rest of the day delving into barriers and drivers for a change effort that would seek to overhaul teaching practices, brainstorming ways to mitigate obstacles and leverage existing resources, and listing allies and change agents who would be on board to help when we returned home. We decided to focus on STEM faculty development based on an urgent campus need to align instructional practices in use with those that have been demonstrated to be most effective and inclusive.

What emerged from this process was a program called REFLECT. The REFLECT program at the University of Portland is a 3-year pilot program funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF DUE IUSE:EHR #1710735). Our program has been successfully leveraged to create systematic change at our university and beyond, but our story of why this worked is a useful narrative for any university interested in changing the culture of improving STEM teaching on campus.

2 Background

2.1 Model of Change

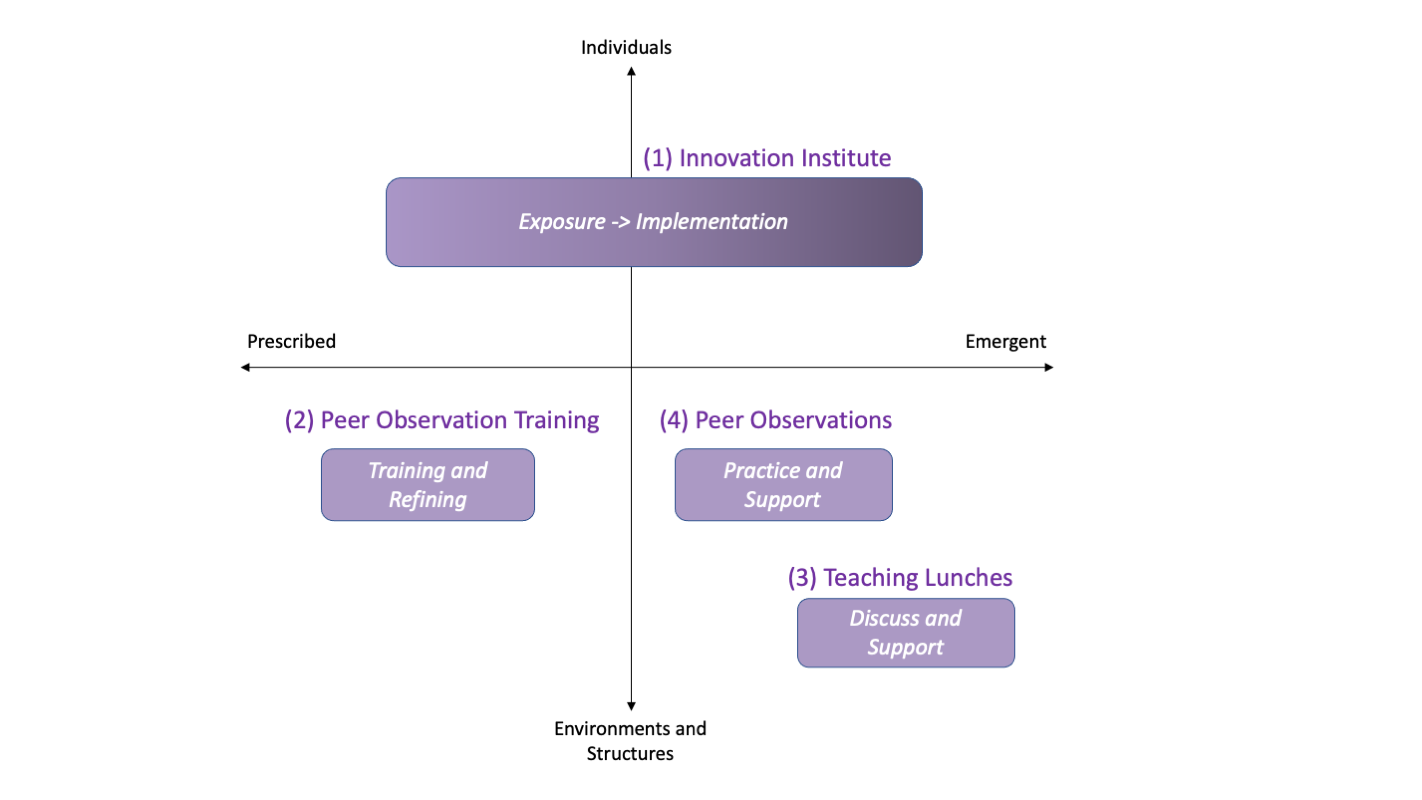

The literature on institutional and cultural change is rich and deep. We started our journey by thinking about some of the most popular change models and how they might be applied on our campus. Fisher and Henderson (2018) have a great review of the different change models and contrasts them for different groups. Since none of our team members had high-level leadership roles on campus, we were drawn to emergent structures for change rather than prescriptive models. We also used a grid visualization developed by Henderson et al. (2011) to help us organize our thinking about change. One method we used was to consider how we could address each quadrant of the grid on our own campus as shown in Figure 1.

In selecting a theory of change to which we would anchor our work, we considered the relatively recent ways in which change theory has been adapted for higher educational use (Reinholz & Apkarian, 2018). These recommended adapting methods that align with individual beliefs, include long-term interventions, and align with institutional culture (Henderson et al., 2011). When possible, we sought to avoid the practices that change literature considered less helpful, like top-down policies.

These findings guided us, and continue to give us signposts as we move forward with the project. This intentional approach supported faculty autonomy and allowed us to meet participants at any stage of “adoption readiness,” with an eye toward moving everyone forward from their own starting point. Each faculty member was on a unique journey from awareness to curiosity to mental tryout to actual trial and finally to adoption.

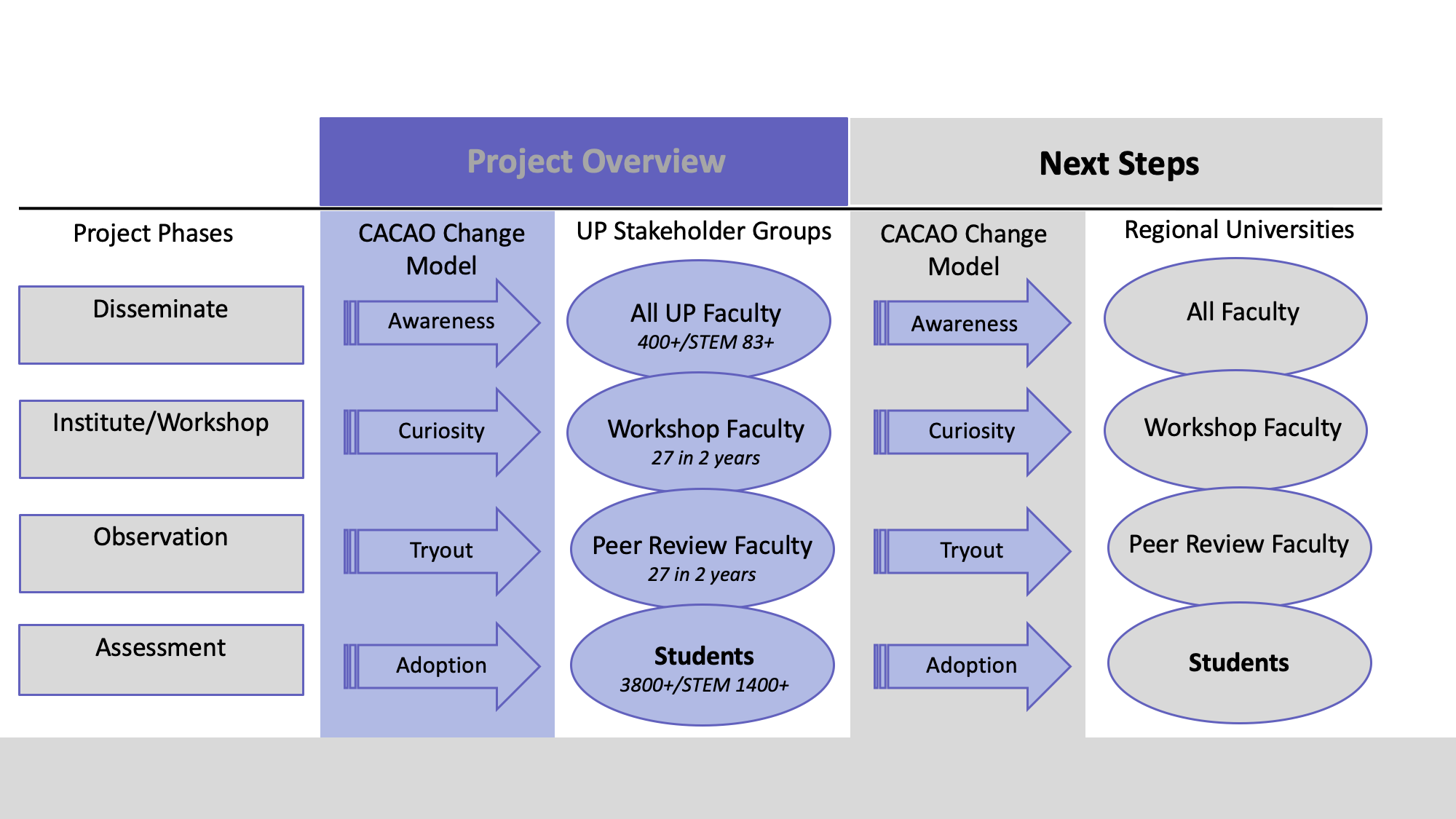

We selected the CACAO model for change (Marker et al., 2015) in part because it is flexible enough to allow change agents to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of the proposed change, incorporate the beliefs of adopters and their relative stages of adoption, and consider the institutional context in recruiting a diverse project team and developing a customized plan. That is, it allowed us to meet our change agents where they were on the adoption spectrum, and for the changes to be emergent, rather than prescribed. There are four dimensions addressed by the CACAO change model: Change, Adopters, Change Agents, and Organization. Each dimension considers the proposed change and guides thinking about mindset relative to change (awareness, curiosity, mental tryout, actual trial, sustained adoption). The dimensions include thinking about organizational hierarchy and matching change agents with roles. We found this framework helpful as we organized several elements of institutional change. Our project overview, with the CACAO elements, is shown in Figure 2.

2.2 Peer Observation of Teaching

The primary tool we used to sustain and inspire change is faculty peer observation because it offers many benefits to the instructors (Bernstein, 2008). One of the most important benefits is providing alternative data from traditional student evaluations of teaching. Other benefits of peer observation include teaching growth for the observer and the one observed (Gormally et al., 2014; Martin & Double, 1998) and improved faculty relationships.

The challenge for most faculty is the fear associated with peer observation and time for observations. Fear is often rooted in concerns about observer bias and power relationships in academia, such as those between untenured or contingent faculty and senior faculty and department chairs (Brent & Felder, 2004; Lomas & Nicholls, 2005). The time required for peer observation is also a factor, particularly with observation methods that require significant training time for calibration (Smith et al., 2013).

Many peer observation protocols have been developed over time for STEM classrooms. To understand this landscape, we did a careful literature review of existing protocols (Dillon et al., 2019). We found most existing protocols focusing on STEM faculty were summative (Brent & Felder, 2004; Drew & Klopper, 2014; Eddy et al., 2015). Others focused on the time that students and instructors spent in specific activities like the Classroom Observation Protocol for Undergraduate STEM (Smith et al., 2013); these protocols required the most training time (Hora et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013). Still other protocols focused on student engagement and student outcomes rather than faculty formation (Lane & Harris, 2015; Shekhar et al., 2015). Table 1 provides a summary of our protocol in the context of other work.

| Peer Observation Framework Elements | Traditional Peer Observation Protocols | REFLECT Peer Observation Protocol |

| 1. Pre-Observation Meeting | X | X |

| 2. Dimensions of Instruction | X | |

| 3. Pre-Observation Self-Assessment | X | |

| 4. Classroom Observation | X | X |

| 5. Student Minute Papers | X | |

| 6. Observer Student Comment Summary | X | |

| 7. Post-Observation Meeting | X | X |

After careful review of the existing protocols, we determined that we would develop our own with a specific goal of providing formative feedback to faculty that would support cultural change on our campus (Dillon et al., 2019). Our peer observation is unique in the way it allows faculty to select a specific dimension of teaching to be observed, making the observation a more manageable time commitment, and allowing the observed faculty member to have control over which aspects of their instructional practice are being considered. The dimensions of teaching in the REFLECT peer observation protocol are listed below, with new elements under development at this time. Additional details about the protocol and the design methods used for the sections are included in prior work (Dillon et al., 2019).

- Clarity of instruction

- Use of technology

- Responding to student thinking

- Challenging content

- Equity of student engagement

- Goal-Oriented instruction

- Types of student engagement

- Group work

- Other (to be developed by your observation team)

3 Method for Change Leader Creation

3.1 REFLECT Institute

We designed the REFLECT Institute based on key ideas we read in the change literature. There are several elements that we built into the institute to create change leaders. Each of these is a lesson learned and a take-away from our own work.

First lesson: motivate faculty change based on incentive structures on campus. We could have named our training “faculty development,” but we know that most faculty perceive faculty development to be prescriptive (or required). In contrast, we wanted everything about our workshop to be focused on nurturing change. By making it clear that we had a selective process to be included, we made our STEM institute something worthy of adding to a vita. We signaled the importance of taking an intentional deep dive into teaching practice with participant titles (STEM Innovation Fellow), labeling of our work together (REFLECT Institute), and by highlighting the work by reporting it to our administrators. Once the faculty were selected for the institute, we published their names in our campus newsletter and emailed the Deans and Provost with a list of their names. At the conclusion of the institute, we gave them each a nameplate for their office that made it clear they were part of the instructional change leadership on our campus.

Second lesson: create a culture of change agents. This was an important facet of the workshop. Many trainings are available about evidence based instructional practices (EBIPs). What makes our training unique is the way we wove in the elements of change on campus. We were explicit, and told our participants repeatedly they were going to become change agents. We included one activity where our participants crafted a vision statement about teaching on our campus. This allowed all the faculty participants to see themselves as change agents, as shown in an example crafted by the members of our 2019 cohort:

After the participants crafted a vision statement, we emailed it to the Deans, Provost, and President of the University and gave credit to the individual faculty participants. This small act made it clear to the leadership on our campus that our cohort of faculty participants had a leadership role in each unit for creating this change. We made it clear to the participants that we planned to support them in creating change on this campus at the highest levels.

Another important structure in the workshop for supporting change was making sure each participant spent a significant amount of time building trust with other change agents from across campus. To accomplish this, we designed the activities so participants changed tables and groups frequently, most often outside of discipline groups. This was important for them to build trust in future peer observation partners, but also to create conversations around change at each table.

Third lesson: compensate faculty participants for their time and effort. We gave each faculty participant a stipend for their time. On our campus, the administration likes to talk about how focused on excellent teaching we are in student brochures, but few financial incentives exist. We did not provide much funding, but we made it clear we valued this work in the same way as disciplinary research. In Levers for Change, Laursen (2019) concludes that external rewards and policies are needed for the adoption and implementation of instructional approaches that positively impact student learning.

3.2 Faculty Peer Observation

We developed a formative peer observation protocol as a second tool to facilitate culture change on our campus. The peer observation process had several benefits that aligned with our change strategy.

- The literature on change indicates that many faculty members need ongoing support to sustain energy for change. Faculty partnerships and ongoing contact help support this work.

- The act of observing a colleague using EBIPs may help someone move along the adoption spectrum.

- The positive feedback and self-reflection from being observed may support and grow a newly adopted teaching practice.

We found that faculty peer observation also led to other collaborations on campus, an exciting take-away. One example was a microbiologist and environmental engineering research collaboration. The two faculty members met through the peer observation process and the REFLECT institute. A few months later, a research challenge led the environmental engineering professor to ask for collaboration on a water-cleaning study. The project recently led to a peer reviewed paper in a journal (Beattie et al., 2019).

Another exciting facet of the peer observation protocol was the support it provided to faculty that wished to work on improving diversity and inclusion in the classroom. The dimension of teaching that is by far the most popular for faculty in the first cohort was “Equity of Student Engagement.” This part of the protocol provides faculty tools for understanding if they are supporting all students in the classroom. We are currently working to develop new dimensions of teaching that would focus on best practices for diversity and inclusion.

The peer observation process served as a tool for self-reflection as well as collaboration, as noted by prior researchers (Cosh, 1999). Faculty participants were asked to reflect not only on their experience as an observer, but to critically examine their beliefs and the alignment of those beliefs with the realities of their teaching environments. We found the formative peer observation process was an impactful way to elicit, engage with, and potentially shift participants’ beliefs (Peterson et al., 2019).

3.3 Leveraging University Initiatives

The last lesson used to create change on our campus was to strategically leverage other activities on campus. Each university has projects or mission statements that provosts and administrators care about. Determining the projects that high-level administrators spend time thinking about is an important lever for change. In our project, we tried to align our work as part of the solution to specific problems, or to align our work as leadership in specific areas.

One example is how we tied our work to mission at our university. We wrote a small grant that provided funds for lunches focused on “The Joy of Teaching.” These lunches allowed us to gather our REFLECT STEM cohorts several times each semester to discuss teaching through the lens of mission. We invited all members of the community to participate and had wonderful and rich conversations about student-focused teaching practices. We hosted nine lunches over one academic year and averaged 15 participants at each lunch. Most of the lunch themes were closely aligned with specific traits we hope our students (and colleagues) might strengthen in the classroom.

4 Results

4.1 Change Leaders Created

After faculty had participated in the REFLECT project for one year, we sent them a survey online using Qualtrics. The survey distribution was reviewed by our university ethics review board. Although the sample size is very small (11 responses), some of the survey responses confirm that we have been successful at creating change agents on our campus. A few key responses have been included in Table 2.

|

Questions |

A great deal |

A lot |

A moderate |

A little |

Not at all |

|

Did the REFLECT Institute increase your awareness of evidence-based teaching practices? |

36.4% |

27.3% |

27.3% |

0% |

9.1% |

|

Did the REFLECT institute inspire or support you to create a culture of reflective teaching at the university? |

54.6% |

36.4% |

9.1% |

0% |

0% |

|

Did the REFLECT institute inspire you to make changes in your classroom? |

27.3% |

54.6% |

18.2% |

0% |

0% |

|

Did the REFLECT Institute support you to increase communication with other disciplines on campus? |

36.4% |

36.4% |

27.3% |

0% |

0% |

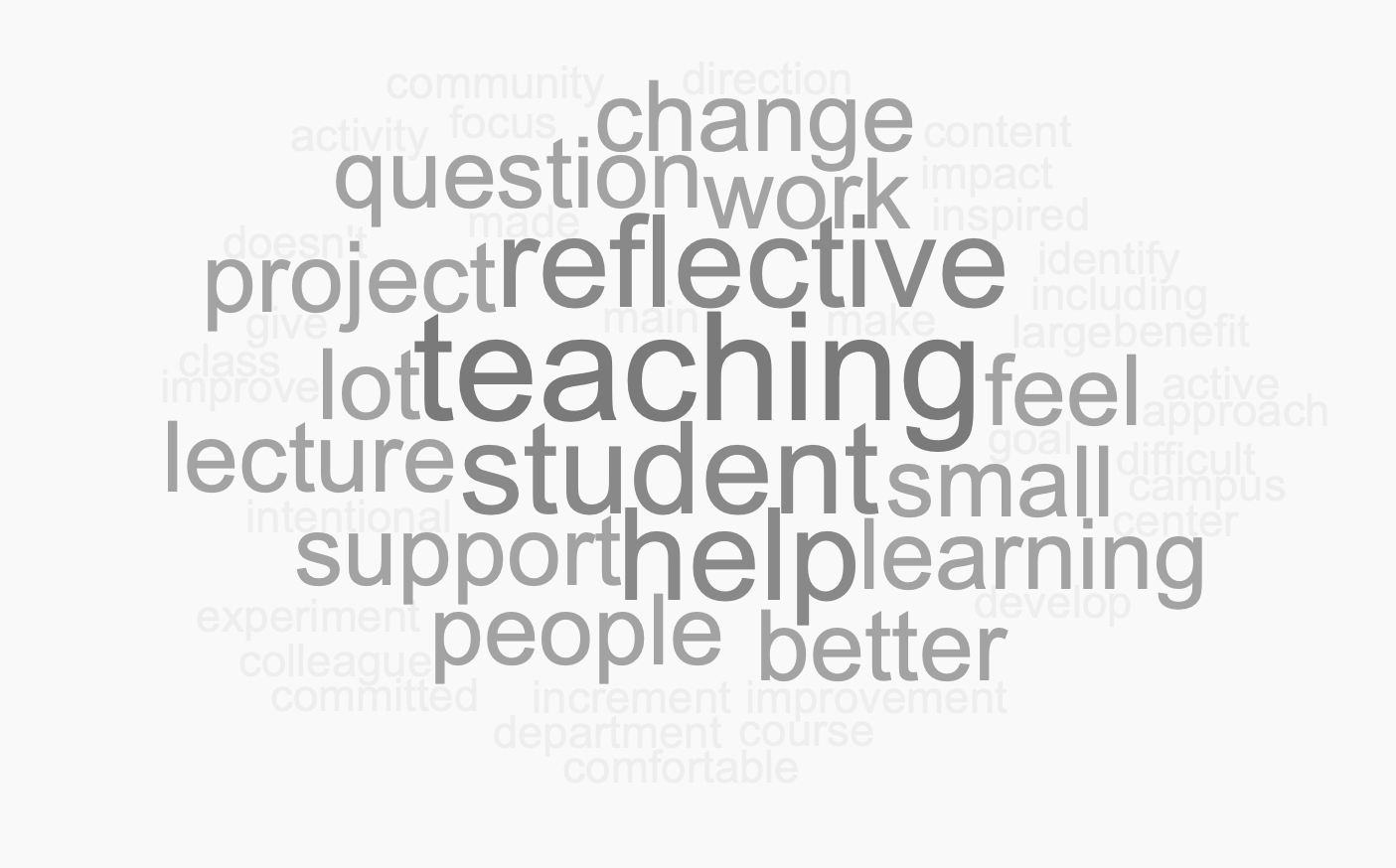

How has participating in the REFLECT Institute influenced your practice of reflective teaching?

- “The project has helped me identify other people on campus who are committed to reflective teaching and can serve as a support system when something new doesn’t go well or my resolve weakens.”

- “I feel more comfortable taking small incremental risks in my teaching. I understand that these changes may be difficult for my students, but it’s ultimately to their benefit.”

- “Having a community that pushes for better teaching and learning practice provides the support I need to keep doing the work … Especially when others do not or question trying new things.”

Another data point in the creation of change leaders surfaced during our annual faculty development day. A small group from our first cohort hosted a session on the importance of peer observation. This brave group of leaders did this without any guidance or support from the REFLECT leadership team, strong evidence that we have empowered our participants to carry the banner for educational change on our campus.

The external evaluation of our project also suggests success in several ways. Prior to participating, all but one of our Fellows reported having negative experiences with peer observation, citing nervousness, fear, and intimidation around the experience. After working with our team, their cohort colleagues, and utilizing the REFLECT protocols, faculty expressed much more positive feelings about observation, including the following:

- “It prompted me to think about things to do in my class. Being observed caused me to pick up on things I may not be noticing.”

- “I loved peer observation. I would like to make that part of our evaluation process.”

Faculty participants also reported implementing changes both to pedagogy and assessment that they learned about in the REFLECT institute. These included group work/group projects, technology, project-based learning activities, peer review, jigsaw, think/pair/share, and gallery walk. Some also talked about assessment techniques they tried: zero consequence quizzes, feedback on and homework solutions posted online, pretests, informal group discussions. All faculty said they would continue with those additions, improvements, and changes the next time they taught that class.

4.2 Institutional Change Created

As our project continues, we have directly trained 30.5% (27 members) of the STEM faculty at the University of Portland. Each STEM unit on campus has included at least one participant; in most units, we have several faculty members/change agents. At least four program chairs have been participants in the REFLECT project, and are working to make peer observation common practice. It has become routine for faculty in mechanical engineering, with 40% of the faculty participating in the REFLECT project. In the mathematics department, half of the full-time faculty (seven members) are involved in REFLECT either as project leaders or as STEM Innovation Fellows.

When surveyed, the REFLECT cohorts responded to several question prompts. A few informative responses are included here that support our hypothesis of change on our campus. Did you have a favorite moment or positive experience using the REFLECT Peer Observation Protocol? What worked well?

- “Probably that I learned just as much observing as being observed.”

- “The most effective part of this experience was discussing teaching with another faculty member. The protocol provided a framework for these discussions.”

Give a specific example of something that you changed in your class during this project. How did it go?

- “I attempted discussions with the entire class (25 students), and really worked on strategies to give all students the chance to participate. I thought it went really well, and now that I am over my initial fear/hesitation, I will definitely try it some more. The energy and points of view of the entire group made the discussion informative, interesting, and enlightening.”

- “Using the word ‘conjecture’ for every student idea—this worked well as it helped me to not be immediately evaluative of their ideas. It also allowed for other students to evaluate ideas rather than just me saying if an idea was worth pursuing. I allocated more time for students to share their ideas with each other through think-pair-share, through speed networking, through problem-solving, and through gallery walks. Doing these things helped me re-center that my discipline is collaborative and it is important to give students a chance to practice collaboration and sharing ideas in the classroom environment.”

Our external evaluator for the projected summed up the key element of institutional change we created, “For most, a major advantage of being involved in REFLECT was being part of a community with a common mindset: it was ‘good to find other people on campus thinking about how they teach and improving their teaching and so that was great.’ Being a part of REFLECT did impact thinking about instruction. As one instructor put it, I learned to try new things and ‘give myself permission to fail miserably.’ All participants were happy to have been part of the project and planned to continue incorporating EPIBs into their instruction.”

5 Discussion

Our research team has confirmed that institutional change is a journey, much like teaching is. Each institution has a culture and pressure points that can be leveraged by emergent and prescriptive change methods to move the needle. We believe that formally and systematically empowering change agents on campus can be supported with formal and formative faculty peer observation.

At our own institution our next steps are to continue training STEM faculty in peer observation and change agency. We hope to build our work at the regional and national level. At other universities our methods could be adapted and enhanced. This work is underway at the University of Calgary, where grant funding has allowed the training of one cohort in the fall of 2019. One cohort has also been trained at the Columbus State University in Georgia. In both cases, the type of training and change agent conversation have taken different forms, but all the early adopters have included the peer observation protocol as a foundation for institutional change.

Our journey with REFLECT continues. Since 2016, when this idea emerged, we have developed our own vision for our campus, applied for and received funding, trained faculty to change their pedagogical practices and supported them in implementation. We developed and piloted a new type of peer observation protocol for formative assessment of teaching. Whenever our energy flags for a moment, our team returns to our mantra, which is tied to our vision for the ways that our changes could impact, and have impacted, our community:

Your teaching matters. Make it matter more.

6 About the Authors

Stephanie Anne Salomone is the Director of the STEM Education and Outreach Center and Associate Professor and Chair of Mathematics at the University of Portland.

Heather Dillon is a Professor and Chair of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Washington Tacoma.

Tara Prestholdt is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Portland.

Valerie Peterson is an Associate Professor in the Department of Mathematics at the University of Portland.

Carolyn James is Calculus Coordinator and Instructor in the Mathematics Department at University of Portland.

Eric Anctil is an Associate Professor of media and technology and director of the Higher Education and Student Affairs Program at the University of Portland.

7 References

Beattie, A., Dillon, H., Poor, C., & Kenton, R. (2019). Solar water disinfection with parabolic and flat reflectors. Journal of Water and Health, 17(6), 921–929. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2019.174

Bernstein, D. J. (2008). Peer review and evaluation of the intellectual work of teaching. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 40(2), 48–51. https://doi.org/10.3200/CHNG.40.2.48-51

Brent, R., & Felder, R. M. (2004). A protocol for peer review of teaching [Memo]. American Society for Engineering Education. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265997249_A_protocol_for_peer_review_of_teaching

Cosh, J. (1999). Peer observation: A reflective model. ELT Journal, 53(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/53.1.22

Dillon, H., James, C., Prestholdt, T., Peterson, V., Salomone, S., & Anctil, E. (2019). Development of a formative peer observation protocol for STEM faculty reflection. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(3), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1645091

Drew, S. & Klopper, C. (2014). Evaluating faculty pedagogic practices to inform strategic academic professional development: A case of cases. Higher Education, 67(3), 349–367. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43648658

Eddy, S. L., Converse, M. & Wenderoth, M. P. (2015). PORTAAL: A classroom observation tool assessing evidence-based teaching practices for active learning in large science, technology, engineering, and mathematics classes. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(2), ar23. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe-14-06-0095

Fisher, K. Q., & Henderson, C. (2018). Department-level instructional change: Comparing prescribed versus emergent strategies. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-02-0031

Gormally, C., Evans, M. & Brickman, P. (2014). Feedback about teaching in higher ed: Neglected opportunities to promote change. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-12-0235

Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(8), 952–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20439

Hora, M. T., Oleson, A. & Ferrare, J. J. (2013). Teaching Dimensions Observation Protocol (TDOP) user’s manual. Wisconsin Center for Education Research. http://tdop.wceruw.org/Document/TDOP-Users-Guide.pdf

Lane, E. & Harris, S. (2015). Research and teaching: A new tool for measuring student behavioral engagement in large university classes. Journal of College Science Teaching, 44(6), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.2505/4/jcst15_044_06_83

Laursen, S. L. (2019). Levers for change: An assessment of progress on changing STEM instruction. American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/levers-for-change-WEB100_2019.pdf

Lomas, L. & Nicholls, G. (2005). Enhancing teaching quality through peer review of teaching. Quality in Higher Education, 11(2), 137–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320500175118

Marker, A., Pyke, P., Ritter, S., Viskupic, K. Moll, A., Landrum, R. E., Roark, T., & Shadle, S. (2015). Applying the CACAO change model to promote systemic transformation in STEM. In G. C. Weaver, W. D. Burgess, A. L. Childress, & L. Slakey (Eds.), Transforming institutions: Undergraduate STEM education for the 21st century (pp. 176–188). Purdue University Press.

Martin, G. A., & Double, J. M. 1998. Developing higher education teaching skills through peer observation and collaborative reflection. Innovations in Education & Training International, 35(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/1355800980350210

Peterson, V., James, C., Dillon, H. E., Salomone, S., Prestholdt, T., & Anctil, E. (2019). Spreading evidence-based instructional practices: Modeling change using peer observation. In The 22nd Annual Conference on Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education (pp. 801–810). Mathematical Association of America.

Reinholz, D. L., & Apkarian, N. (2018). Four frames for systemic change in STEM departments. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), ar3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0103-x

Shekhar, P., Demonbrun, M., Borrego, M., Finelli, C. J., Prince, M. J., Henderson, C., & Waters, C. (2015). Development of an observation protocol to study undergraduate engineering student resistance to active learning. International Journal of Engineering Education, 31(2), 597–609.

Smith, M. K., Jones, F. H. M., Gilbert, S. L., & Wieman, C. E. (2013). The Classroom Observation Protocol for Undergraduate STEM (COPUS): A new instrument to characterize university STEM classroom practices. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-08-0154