19 Leveraging Organizational Structure and Culture to Catalyze Pedagogical Change in Higher Education

Carrie Klein, Jaime Lester, and Jill Nelson

Active and inquiry-based learning has a positive effect on student engagement at all levels of curriculum (e.g., Coalition for Reform of Undergraduate STEM Education, 2014; Freeman et al., 2014; National Research Council, 2012). These approaches have an even greater influence on historically underrepresented populations, particularly women, and on students who held lower achievement rates (Kogan & Laursen, 2014; Laursen et al., 2014). Despite their value, the change required to integrate these practices can be difficult, especially in higher education. Motivating faculty to make significant changes to their teaching practices is challenging (Austin, 2011). As a result, there has been uneven adoption of active learning and inquiry-based approaches.

The literature on pedagogical change in academic departments indicates that departmental norms and organizational structures have a large impact on the way STEM faculty teach (Austin, 2011; D’Avanzo, 2013; Brownell & Tanner, 2012; Henderson et al., 2012; Lee, 2007; Sunal et al., 2001; Fairweather, 2008). Institutional barriers, including fragmented organizational sub-structures and sub-cultures, mean that innovative teaching practices often become siloed (Bergquist, 1992; Birnbaum & Edelson, 1989; Bolman & Deal, 1991; Kezar, 2011; Tierney, 2008). The dependence of change on departmental norms and siloed institutional structures makes it difficult to spread changes, like innovative teaching practices, across higher education. Given this context, it is important to investigate how organizational change practices that mitigate fragmentation and leverage departmental norms can be used to diffuse pedagogical innovations within and beyond individual and department level practice.

1 Project Goals

The purpose of our current National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded IUSE project (1821589) is to better understand the process of organizational change for pedagogical diffusion that occurs via peer-to-peer learning communities engaged in implementation of active- and inquiry-based pedagogy in STEM fields. We are interested in how these teams, which we call Cross-course Communities of Transformation (CCTs), can be used to facilitate broad adoption of active learning within departments and across STEM disciplines. We also want to develop knowledge of how faculty-driven, grassroots approaches to change combined with institutional support can build a culture of active learning. The purpose of this work is to study effective strategies for removing barriers for faculty implementation of new, evidenced-based teaching methods and to prepare the next generation of diverse STEM educators.

Relying on extant literature and best practices from organizational theories of change and instructional and pedagogical design, the following research questions are guiding our work: 1) How do the tactics outlined in grassroots change theory help to create sustainable course-level and department-level changes toward the use of inquiry-based learning? 2) To what extent do graduate apprentice instructors and undergraduate learning assistants assist in diffusing course-level change to the department or college level? 3) How do grassroots tactics, implemented through CCTs, influence organizational learning and diffuse course-, department-, and institution-level change? We provide a model for organizational change, based on CCTs, discuss the model-informed change process, share observations from our work and conclude with practical recommendations for faculty and administrators seeking to create organizational change.

2 Change Model

The theoretical framework for this project is informed by higher education focused grassroots change and organizational diffusion models. Developed by Kezar and Lester (2011), the grassroots leadership model provides evidence and a mechanism for understanding how to engage individuals and teams to achieve organizational change on college campuses. Grassroots leadership research (Kezar & Lester, 2011) shows that providing professional development opportunities, enabling faculty discussion of curricula and classroom activities, working with and mentoring students, using data to tell a story, partnering with stakeholders, and leveraging existing networks are effective change mechanisms in higher education that work to mitigate the organizational structures and norms that can limit change.

Diffusion and organizational learning are central to the grassroots model. Integrating change into higher education institutions requires altering individual mindsets or perspectives, including those of campus leadership. Organizational learning, a social cognitive change theory, is a process of sharing knowledge that guides behavior and shapes meaning for individuals and groups (Crossan et al., 1999). Organizational learning consists of four processes: knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational memory, and occurs when shared knowledge embeds in organizational structures, processes, and culture (Huber, 1991). Once embedded, change can diffuse further into the institution (Rogers, 2003).

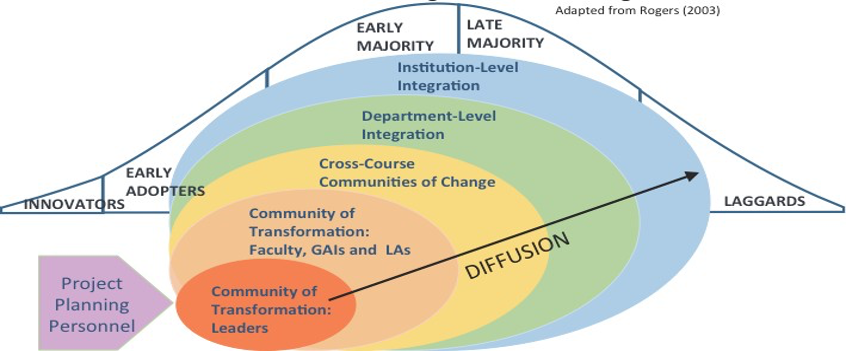

Kezar and Lester (2011) note that diffusion requires the convergence of bottom-up (grassroots) and top-down efforts. This project combines top-down support with a grassroots design that begins with educational innovators within the faculty and ends with the laggards identified in Rogers’ (2003) diffusion theory. Figure 1 provides more detail on how this model applies to the CCT change efforts in this study.

We seek to expand Kezar and Lester’s work by examining the impact of CCTs on changing pedagogy, processes, and culture through learning and diffusion. Peer-to-peer learning communities have been shown to provide support for organizational learning (Mittendorf et al., 2006), the development of new pedagogical interventions, and shifting faculty values surrounding teaching and learning (Snyder et al., 2003; Boud & Middleton, 2003; Davis & Sumara, 1997; Gallucci, 2003; Sanchez-Cardona et al., 2012; Viskovic, 2006). The CCT model draws from a prior faculty teaching development project in which discipline-based learning communities were used to support sustained adoption of active learning practices in STEM (Nelson et al., 2016). While the previous approach encouraged participants to select strategies to address their individual needs, the CCT model focuses on building a shared vision for the nature of the change toward active learning.

3 Putting the Model into Practice: The Process of Change

As of Fall 2019, two of the planned four CCTs have begun the process of integrating active learning pedagogy and change across introductory math and physics courses. Because our project staggers the start and implementation of CCT work, the Math CCT and Physics CCT are at different stages of the change process (to be followed by Computer Science and Biology). Since Spring 2019, the Math CCT has worked to incorporate pedagogy change in introductory calculus courses. Meanwhile, the Physics CCT members began their efforts related to introductory physics courses in Fall 2019. As a result, this paper is focused on the Math CCT change process.

In Spring 2019, project team members met with faculty and graduate teaching assistants (GTAs) in the Math department to provide an orientation explaining the project and providing insight into the benefits of active learning and the process of organizational change. Attending and speaking in support of the project was a vice provost, college dean, and the chair of the Math department. The strong administrative support of this effort is tied to campus-wide efforts to improve active learning strategies and resources. Improving teaching and learning is tied to both our institutional identity as a large, regional comprehensive public university and our most recent strategic plan, which sought to balance our very high research status with our commitment to public education. The active learning discussion was led by a nationally recognized disciplinary expert on active learning pedagogy in math. The majority of 50 Math faculty members participated in the orientation.

Following this orientation, Math CCT members, who are a subset of early-adopter faculty from the Math department (nine total), began meeting every two weeks to identify areas for change and to plan for change implementation. Facilitating these meetings is a departmental change agent, who is also a member of our research team. The change agent is a well-respected member of the Math department, having worked at the institution for nearly 30 years and previously been department chair. They are also actively engaged in active learning on a national level. In these meetings, Math CCT members have established change goals, engaged in peer-learning, and discussed effective active learning practices that they have used in their own classes. To support their learning in the active learning space, the CCT change agent has also invited speakers from outside the institution to provide seminars on active learning and inquiry-based classroom practices. The research team provided ongoing support to the change agent and CCTs in monthly meetings, connecting the change agent with resources and strategies to leverage their departmental norms and structures to facilitate change.

As a group, the Math CCT members decided to restructure course recitation sessions for introductory calculus courses to include active learning practices, which began in Fall 2019. This decision was based on review of disciplinary literature and on departmental data. To support this change, Math CCT members hired and trained a number of GTAs and undergraduate learning assistants (LAs) and created bi-weekly meetings to support GTA professional development. These meetings provide peer-learning, sharing, and training opportunities, with additional guidance provided by the change agent.

To study the process of organizational change, we are using a collective case study design to allow for “in-depth exploration of a bounded system (e.g., an activity, event, process or individuals) based on extensive data collection” (Creswell & Poth, 2012, p. 476) designed around a specific theory and literature (Stake, 2005). The use of a collective case study will allow us to study organizational change from multiple, interrelated perspectives of the CCTs as they go through the change process. Our primary data collection methods are observations of CCT meetings and interviews with CCT members. We have also collected reflective memos from CCT change agents. Data collection is focused on CCT processes, change, and change management. Consistent with methodological norms of qualitative inquiry, the systematic coding of these data (i.e., interview transcripts, documents, field notes and memos) serves as the primary means of data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Examples of current codes include: shared leadership, visible commitment, shared goals, respect, experience, culture, process, communication, and assessment.

4 Observations

Although we have many emerging findings, among the most prominent observations we have made are the importance of aligning process and culture and of leveraging visible and respected leadership across levels to encourage organizational learning and change diffusion.

4.1 Alignment of Change to Cultural Norms Encourages Adoption and Learning

Attention and alignment of organizational change efforts to cultural norms matters to promote and diffuse organizational learning and change. Across Math CCT member interviews, participants communicated that shared leadership as a mechanism for change is culturally valued in their department. The chair of the department explains, “So usually the way things change is that, um, you know, someone has an idea and they get a few people on board with it. They implement the idea, people see that it’s successful, and then more people kind of jump on that.” The Math CCT change agent used this cultural perspective to guide his facilitation of meetings by encouraging shared approaches to change. We observed that while the change agent calls CCT meetings to order, the group participates collaboratively in conversations about interests, goals, and outcomes and in learning about inquiry-based pedagogy. In this case, when the process of group work is aligned with the cultural value of shared leadership, it can act as a catalyst for change.

Equally important for the Math CCT is collegial relationships. Multiple participants noted that respect for their colleagues and their colleagues’ ideas is valued culturally. As a tenure-track faculty member noted, “We’ve worked well together. We’re very respectful of each other’s ideas.” Examples of respectful relationships were observed across Math CCT and GTA meetings. As a group, participants were supportive of each other’s ideas and encouraged full participation of members (including GTAs). This culturally held value of respect has also informed the processes associated with the change work on which the CCT members are focused. A term faculty member explained that a respectful environment has resulted in a CCT group that has “done a really good job of communicating … you know, we’re a pretty cohesive group already.” Their cohesiveness has laid the groundwork for effective work to take place, resulting in what another term faculty described as “a good initial plan of attack on how to kind of get what we want out of this.” In this case, by aligning process to a cultural norm of collegial relationship interactions, Math CCT members were able to effectively move their active learning goals forward.

Among the work they have moved forward is pushing organizational learning beyond their initial group. The Math department and, as we have observed, CCT members in particular value professional development and growth. The CCT’s work and seminars are seen as a way for faculty members to grow professionally, as a new tenure-track faculty member notes, “I really do believe in active learning, but I struggle with being an active learning teacher. So, I think that the [CCT] group helps me kind of get ideas, confidence from it, um, and to bounce ideas off of people who do it successfully or have seen it in other places.” The cultural importance of learning and developing professionally acted as a lever for change in this new faculty member. By aligning cultural norms with change efforts, CCT members have created learning opportunities for faculty in the department. Moreover, incorporating learning seminars was an important strategic decision by the change agent, as participants noted that the seminars were among their favorite parts (beyond seeing students’ development and growth) of participation in this project.

4.2 Visible and Respected Leadership at Multiple Levels Legitimizes Change Efforts

Tied to the culture and process is the role of visible and respected leadership, at multiple levels, to legitimize change efforts. From CCT orientation on, there has been visible support for this project by the administration and department leaders. At the Math CCT’s orientation, a vice provost, college dean, and department chair were there to signal their support. The department chair has also attended Math CCT meetings. Notably, as mentioned in the change agent’s memos, both he and the department chair have led and participated in robust conversations about the change efforts in departmental meetings, which has resulted in increased interest by faculty. This top-down, visible support of the inquiry-based change efforts through this project have helped facilitate faculty interest and involvement in the process.

However, to effectively facilitate change, grassroots leadership is also needed. CCT members universally indicated their respect for the change agent’s experience and his social capital among the group as a vital component of their participation in the change efforts. For example, when we asked a term faculty member why she joined the CCT efforts, she explained that she and the change agent had similar perspectives on teaching and “had great conversations about teaching, like, way before [the start of the CCT’s work].” The change agent’s prior relationship and teaching experience was a draw for this CCT member. Similarly, the department chair explained how the change agent’s reputation acts as a boon to the active learning change efforts:

The Math CCT change agent’s experience and reputation with department members helped legitimize the active learning efforts in the department. The legitimation was given further heft through the support of top-level leaders and the visibility both top-down and grassroots actors have given to the process.

5 Recommendations for Practice

Based on the initial findings from our project, we have a number of recommendations for both faculty and departmental administrators seeking to enact organizational change within their disciplines and across their campus communities.

5.1 For Faculty

Faculty interested in changing their departmental culture and practices should leverage resources and relationships to help catalyze that change. To start, we recommend seeking out resources (e.g., literature, evidence, examples, experts, etc.) and sharing them broadly within your departmental community to help legitimize your efforts. These resources can help establish shared understanding and goals with colleagues around a proposed change strategy. Importantly, these efforts should align with departmental cultural norms, including acceptable communication and meeting processes, to both encourage participation and increase buy-in from potential participants. As Lee (2007) has found, attention to department-level culture is integral to change.

The attention to culture is tied to effective grass-roots change efforts. Kezar and Lester (2011) found that effective change agents are able to leverage departmental and organizational culture for change efforts. Change agents should leverage both departmental culture and their social capital to not just encourage participation in the change process, but also to advocate for people, spaces, resources, and other needs related to desired change. Austin (2011) argues that these aspects of organizations can be used to leverage a willingness by faculty to innovate their teaching practices. Central to long-term change is the inclusion of future generations of disciplinary colleagues, so graduate and undergraduate students (GTAs and LAs in this project) should be mentored in the change process by actively including them in CCT meetings, seminars, and other events. Finally, CCT change work, progress, strategies, “wins,” and related professional development opportunities should be made visible by sharing them broadly, both within and beyond the department. This socio-cognitive approach of leveraging culture, capital, and organizational learning aligns with Crossan et al.’s (1999) socio-cognitive approach and provides opportunities for learning to be embedded and diffused through the fabric of organizations (Huber, 1991).

5.2 For Department Leadership

Among the best things departmental leaders can do to support organizational change are to provide visible, top-down support while simultaneously allowing for bottom-up leadership. This dual level of support can help encourage organizational change by providing visibility and legitimization to organizational change efforts (Kezar & Lester 2011). This support of CCT work can be shown through attending change strategy meetings and seminars and by working with change agents to advocate at the college or institutional level for people, spaces, resources, incentives, and rewards. Departmental leadership can also work with change agents to leverage organizational culture to support desired changes. To encourage department-level buy-in, department chairs should provide incentives, rewards, and professional development opportunities to department members. Like with other organizational resources, Austin (2011), in her study of faculty pedagogy change, found incentives and rewards (e.g., course buy-outs, increased funding, formal recognition, etc.) are effective institutional and managerial levers for change. Leadership should also give time during department meetings for change agents, CCT members, or other project champions to share change efforts, processes, strategies, successes and opportunities. Finally, department leadership would champion change strategy “wins” in deans’ and department chairs’ meetings, to incorporate organizational learning and change within and beyond the department level. Effective communication of positive change outcomes, within and beyond the department-level, is central to grassroots effectiveness, organizational learning, and diffusion of change (Crossan et al., 1999; Huber, 1991; Kezar & Lester, 2011; Rogers, 2003).

6 Conclusion

The first year of this project has created an incredible opportunity for learning for project team members and for members of the Math CCT. Course recitation sessions rooted in active-learning inquiry began this fall, and we are beginning to see positive results of that change in students. Math CCT members are still actively engaged in the change process and working toward learning from the first semester of change implementation. As a research team, we are beginning to see how CCTs can work to effectively implement change within the department. Among the positive changes that have occurred are additional faculty joining the CCT efforts and improved outcomes for students in active learning courses. We look forward, as the Math CCT and Physics CCT members begin to meet in the coming year, to how these changes can diffuse across STEM departments and to provide recommendations for necessary conditions for change that can be used across disciplines to improve active learning implementation and, ultimately, student outcomes.

7 Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by a grant from NSF under grant IUSE-1821589.

8 About the Authors

Carrie Klein is a Senior Fellow on the Future of Privacy Forum’s Youth & Education team and an adjunct faculty member in George Mason University’s Higher Education Program.

Jaime Lester is the Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs and Strategic Initiatives and a Professor of Higher Education in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at George Mason University.

Jill Nelson is an Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at George Mason University.

9 References

Austin, A. E. (2011). Promoting evidence-based change in undergraduate science education. National Academies National Research Council Board on Science Education. http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_072578.pdf

Bergquist, W. H. (1992). The four cultures of the academy. Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Birnbaum, R., & Edelson, P. J. (1989). How colleges work: The cybernetics of academic organization and leadership. Taylor & Francis.

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1991). Leadership and management effectiveness: A multi‐frame, multi‐sector analysis. Human resource management, 30(4), 509–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930300406

Brownell, S. E., & Tanner, K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and… tensions with professional identity? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-09-0163

Boud, D., & Middleton, H. (2003). Learning from others at work: Communities of practice and informal learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 15(5), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620310483895

Coalition for Reform of Undergraduate STEM Education. (2014). Achieving systemic change: A source-book for advancing and funding undergraduate STEM education (C. L. Fry, Ed.). Association of American Colleges and Universities. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/publications/E-PKALSourcebook.pdf

Crossan, M. M., Lane, H.W., & White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.2307/259140

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE Publications.

D’Avanzo, C. (2013). Post-vision and change: Do we know how to change? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 12(3), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-01-0010

Davis, B., & Sumara, D. (1997). Cognition, complexity, and teacher education. Harvard Educational Review, 67(1), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.67.1.160w00j113t78042

Fairweather, J. (2008). Linking evidence and promising practices in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) undergraduate education [Status report]. National Research Council Workshop, Washington, DC. https://www.nsf.gov/attachments/117803/public/Xc–Linking_Evidence–Fairweather.pdf

Freeman, S. Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gallucci, C. (2003). Communities of practice and the mediation of teachers’ responses to standards-based reform. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11(35), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v11n35.2003

Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. D. (2012). Four categories of change strategies for transforming undergraduate instruction. In P. Tynjälä, M.-L. Stenström, & M. Saarnivaara (Eds.), Transitions and Transformations in Learning and Education (pp. 223–245). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2312-2

Huber, G. P. (1991). Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organization Science, 2(1), 88–115. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.88

Kezar, A. (2011). Understanding and facilitating organizational change in the 21st century: Recent research and conceptualizations. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 28(4).

Kezar, A., & Lester, J. (2011). Enhancing shared leadership: Stories and lessons from grassroots leadership in higher education. Stanford University Press.

Kogan, M., & Laursen, S. (2014). Assessing long-term effects of inquiry-based learning: A case study from college mathematics. Innovative Higher Education, 39(3), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-013-9269-9

Laursen, S. L., Hassi, M.-L., Kogan, M., & Weston, T. J. (2014). Benefits for women and men of inquiry-based learning in college mathematics: A multi-institution study. Journal of Research in Mathematics Education, 45(4), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.45.4.0406

Lee, J. J. (2007). The shaping of the departmental culture: Measuring the relative influences of the institution and discipline. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 29(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/73600800601175771

Mittendorf, K., Evjset, F., Hoeve, A., deLaat, M., & Nieuwenhius, L. (2006). Communities of practice as stimulating forces for collective learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(5), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610674971

National Research Council. (2012). Discipline-based education research: Understanding and improving learning in undergraduate science and engineering. (S.R. Singer, N.R. Nielsen, & H.A. Schweingruber, Eds.). The National Academies Press.

Nelson, J. K., Hjalmarson, M., Bland, L. C., & Samaras, A. P. (2016, June 26). SIMPLE design framework for teaching development across STEM [Poster session]. 2016 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, New Orleans, LA. https://doi.org/10.18260/p.26187

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Simon and Schuster.

Sánchez-Cardona, I., Sánchez-Lugo, J., & Vélez-González, J. (2012). Exploring the potential of communities of practice for learning and collaboration in a higher education context. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1820–1825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.385

Snyder, W. M., Wenger, E., & de Sousa Briggs, X. (2003). Communities of practice in government: Leveraging knowledge for performance; Learn how this evolving tool … performance outcomes in your backyard. The Public Manager, 32(4), 17–21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/245706269_Communities_of_practice_in_government_Leveraging_knowledge_for_performance

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 443–466). SAGE Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. SAGE publications.

Sunal, D. W., Hodges, J., Sunal, C. S., Whitaker, K. W., Freeman, L. M., Edwards, L., Johnston, R. A., & Odell, M. (2001). Teaching science in higher education: Faculty professional development and barriers to change. School Science and Mathematics, 101(5), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.2001.tb18027.x

Tierney, W. G. (2008). The impact of culture on organizational decision-making: Theory and practice in higher education. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Viskovic, A. (2006). Becoming a tertiary teacher: Learning in communities of practice. Higher Education Research & Development, 25(4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360600947285