10 Research Coordination Networks to Promote Cross-Institutional Change: A Case Study of Graduate Student Teaching Professional Development

Grant Gardner, Judith Ridgway, Elisabeth Schussler, Kristen Miller, and Gili Marbach-Ad

1 Introduction

Academic institutions are complex hierarchical systems where faculty and staff often navigate teaching, research, and service responsibilities between multiple organizational units. Because of this complexity, enacting institutional change can be a challenging endeavor. Even more difficult are change efforts focused on impacting multiple institutions. Different institutions can have different internal structures, policies, processes, and cultures such that change efforts that work at one may not work at them all. As part of a National Science Foundation-funded Research Coordination Network-Undergraduate Biology Education (RCN-UBE) program, our team has been enacting a change project related to graduate student professional development that spans multiple institutions. This chapter highlights our program as a case study into the challenges and opportunities provided by research coordination networks to affect cross-institutional change.

Many institutional change initiatives have focused on encouraging a shift from teacher-centered toward more student-centered pedagogies in faculty members (American Association for the Advancement of Science [AAAS], 2011, 2015; Eddy & Hogan, 2014; Freeman et al., 2014). For example, the Summer Institutes on Scientific Teaching (Pfund et al., 2009) have trained over 2,000 faculty via national, regional, and campus workshops focused on active learning, assessment, and inclusivity. The Promoting Undergraduate Life Science Education network (Brancaccio-Taras et al., 2016) sends regional teams to work with Biology departments to assess their alignment with practices outlined in Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education (AAAS, 2011). Despite a national push to support these changes, adoption of student-centered pedagogies has been uneven across instructors and institutions (Stains et al., 2018).

These aforementioned endeavors are impressive but are working with one highly visible group within the academic community (faculty). Our work focuses on “future faculty” and those who develop their teaching, many of whom are less visible members of the academic hierarchy. This chapter describes the RCN-UBE Biology Teaching Assistant Project (BioTAP) and its efforts to impact multiple units of the academic system in order to promote cross-institutional change specific to graduate teaching assistant (GTA) teaching professional development (TPD). We believe that focusing national change efforts on the instructional beliefs and practices of future faculty and on those in the system who train them can have the broadest and most sustainable impact on teaching practices nationwide (Connolly et al., 2018; Ebert-May et al., 2015).

In the following sections, we briefly describe the BioTAP project and the theory of change that guides it. We detail the change context, long-term outcomes, pre-conditions, activities, and assumptions that have guided this work (Reinholz & Andrews, 2020). Because our efforts focus on individuals at multiple institutions, but with a goal for cross-institutional collaboration, our theory of change considers the hierarchical complexity of institutional systems. The broader question we attempt to answer in this chapter is: how can a research coordination network be leveraged to impact cross-institutional change? We reflect on what has been successful in reaching our project goals with the hope that this case study helps others attempting to facilitate change across multiple institutions.

2 Change Context—Graduate Teaching Assistant Teaching Professional Development

Graduate teaching assistants are critically-important undergraduate instructors (Sundberg et al., 2005), but minimal focus has been placed on their TPD (Schussler et al., 2015). There are a multitude of reasons for this, including: prioritization of research over teaching in graduate professional development (Anderson et al., 2011), little institutional support for instructional training (Schussler et al., 2015), and a belief that training for teaching is not necessary (Love Stowell et al., 2015). As many graduate students are future faculty, improving their teaching at an early career stage could be one mechanism for impacting nationwide instructional reform (Connolly et al., 2018).

Many of the individuals implementing GTA TPD are intra- or inter-institutionally isolated or have less power to impact the system relative to others: non-tenure track faculty members, graduate students or post-doctoral scholars, and/or laboratory instructional staff. This makes institutional change related to GTA TPD different from other efforts driven by national organizations or relatively more empowered faculty members (for example FIRST; Ebert-May et al., 2015 or CIRTL; Austin et al., 2008). BioTAP was created as a network to connect isolated individuals across institutions to effect cross-institutional change related to GTA TPD.

To foster GTA adoption of student-centered pedagogies, there must be effective GTA TPD; however, the network must acknowledge and address the limited empirical evidence guiding GTA TPD practices. BioTAP’s broad goal is to increase the body of empirical research on effective GTA TPD as a means to guide national instructional reform efforts. Our contention is that without these data, it will be difficult to promote institutional change in GTA teaching practices at any institution (Reeves et al., 2016).

The explicit goals of BioTAP are to leverage network stakeholders to: 1) expand and support GTA TPD research and practice collaborations, and 2) synthesize, disseminate, and advocate for research to advance GTA TPD. These goals are dependent on building a vibrant, cohesive, multi-institutional network of individuals focused on enacting evidence-based GTA TPD practices in order to promote instructional change. Achievement of the BioTAP goals would result in the long-term with a network of interacting cross-institutional change agents that is large (many individuals), dense (many connections between individuals), and sustainable.

3 Theory of Change

To guide the network, we developed a theory of change that reflects how our project endeavored to get individual GTA TPD providers at different institutions (inter-institutional) and within institutions (intra-institutional) to work together to effect change in complex systems. We leaned heavily on an article focused on collaborative networks to enact K-12 school reforms (Rincón-Gallardo & Fullan, 2016) because it was about enacting change beyond just a single individual or institution and addressed multiple levels of complex institutional systems. We saw similarities between the authors’ approach of empowering teachers to work together for school reform and our desire to empower GTA TPD providers with the tools to reform GTA TPD at their institutions. This allowed us to articulate assumptions and design activities related to getting multiple individual stakeholders to embrace our project goals.

Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan (2016) proposed eight Essential Features of effective networks (Table 1) and emphasized that each network’s effectiveness in terms of educational change is tied to how well its components function together in the larger system. Applying this model to our program enabled us to assess strengths and weaknesses that might accelerate or prevent BioTAP from reaching its goals.

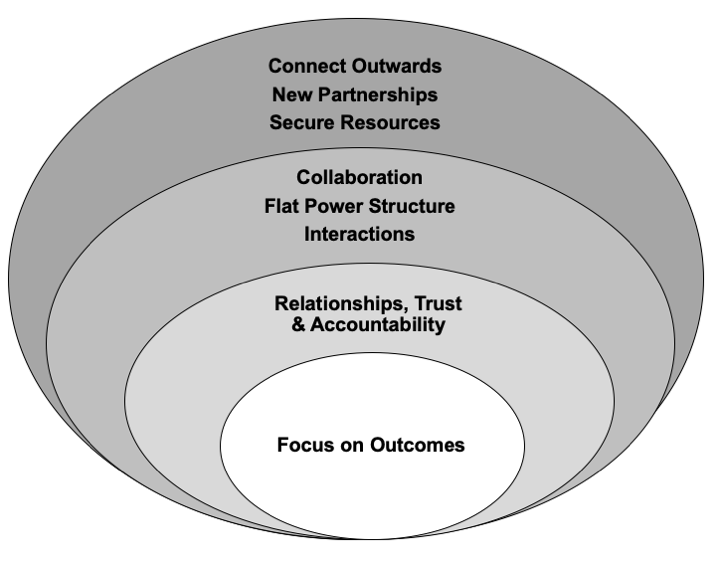

To apply their ideas to our project, we compacted their eight Essential Features into four major themes, or “layers,” that represented steps that would expand our ideas and impact over time (note that these layers are not academic levels, although the network growth over time inherently expands into new academic areas). This somewhat artificial grouping of layers allowed us to plan activities to enact our theory of change and guided our subsequent evaluation of network growth. Figure 1 shows the modified layers (four themes) used as the BioTAP theory of change, based on Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan’s (2016) Essential Features.

| Essential features (Rincón-Gallardo & Fullan, 2016) of effective networks organized from their core to periphery | BioTAP Modification of the essential features, shown using the corresponding layers |

| 1. Focus on ambitious student learning outcomes linked to effective pedagogy. | 1. Focus on network outcomes linked to effective network-building and be ambitious to reach stakeholders. |

| 2. Develop strong relationships of trust and internal accountability. | 2. Build strong relationships, trust, and both internal and external accountability with stakeholders at multiple organizational units (individual, departmental, college, etc.). |

| 3. Continuously improving practice and systems through cycles of collaborative inquiry. 4. Use deliberate leadership and skilled facilitation within flat power structures. 5. Frequently interact and learn inwards. |

3A. Continuously improve networks through cycles of collaborative connecting. 3B. Develop a flat power structure through reduction of the network hierarchy. 3C. Reinforce network ties through frequent interactions. |

| 6. Connect outwards to learn from others. 7. Form new partnership among students, teachers, families, and communities. 8. Secure adequate resources to sustain work. |

4A. Connect outwards to build the network and learn from others. 4B. Form new partnerships at different organizational units. 4C. Secure adequate resources to sustain the network. |

Note: we clustered the eight features of the model into themes most relevant to the BioTAP network as our ideas and impacts grew over time.

3.1 Pre-Conditions, Activities, and Assumptions

Below we describe our theory of change as well as its alignment with BioTAP project activities. In Section 4, we reflect on the success of our project in terms of the outcomes that would be expected if we successfully adhered to the theory of change. Our ultimate goal was to construct a network in which numerous robust connections between individuals would support cross-institutional change; it should be noted that the evaluation of this outcome could be accomplished through social network analysis; however, describing the project evaluation is not the goal of this chapter.

3.2 Model Layers

Model Layer 1—Focusing on Clear Network Outcomes: The first layer is the development of clear outcomes and consistent communication of project goals and outcomes by the leadership team, in our case the Principal Investigators (PIs) and the steering committee. We held a meeting with the PIs and steering committee early in the project to foster communication, refine the project goals, and create a shared vision. This group served as the core of the developing network and anchored the creation of future network connections. This layer reminds us to articulate both short- and long-term outcomes and develop an ambitious plan to reach and communicate with potential stakeholders. A shared commitment to project goals helps us coordinate efforts and progress toward the outcome of a highly-integrated group of individuals who interact to support high-quality Biology GTA TPD research.

Model Layer 2—Building Network Trust and Accountability: The second layer is to build strong relationships, trust, and internal and external accountability among the network individuals. Establishing trust and accountability among the BioTAP PIs from the beginning was invaluable. We found that we appreciated each other’s strengths, opinions, and work ethics, and this led to better initial ideas and products.

Building relationships involved contacting new stakeholders and creating new connections between those stakeholders and our core network. We did this by leveraging our BioTAP listserv and personal connections to reach out to others. Trust and accountability requires bidirectional communication between core members as well as other members of the network, and these connections needed to be robust so they can be sustained over time.

This strengthening of the network connections occurred primarily through the enactment of the BioTAP Scholars program. This program (started in 2017) brings cohorts of individuals from many institutions together to collaboratively develop year-long GTA TPD research projects and enact them with support from the project PIs and their cohort peers. There are currently 66 BioTAP Scholars that include graduate students, postdocs, Teaching and Learning Center members, and tenure- and non-tenure track faculty from 47 institutions (32 are from research institutions and four are international). Many BioTAP Scholars build very strong connections with the PIs and other scholars within their cohort. Recent efforts have focused on connecting members of different cohorts.

To ensure internal and external accountability, we realized that we needed cycles of reflection to improve the program. We spent a year thoughtfully designing the BioTAP Scholars program. It was only after testing our ideas with BioTAP Scholars Cohort 1, reviewing data from our program evaluation, and revising our designs that we felt we were starting to achieve our intended outcomes. Even seemingly small details such as the wording of the BioTAP Scholar application were revised for each cohort. The detail put into the Scholars program and the time spent working closely with Scholars and reviewing our evaluation results built strong relationships and developed trust.

Model Layer 3—Leveraging Collaboration and Flat Leadership Structures in the Network: Our change model involves continuously improving the network through cycles of collaboration between participants, developing a flat power structure through reduction of network hierarchy, and reinforcing connections through frequent interactions (layer 3). The BioTAP community has a culture of frequent interactions and knowledge sharing. Even though the community members are spatially dispersed, we meet regularly through online meetings and virtual conferences. For example, our BioTAP Scholars meet multiple times throughout the year with small groups (“pods”) of their cohort members and two PIs. Pod members share their research progress and receive feedback, with everyone building trust over time that their ideas are valued and equally important to everyone’s progress. Frequently, these discussions lead to new research ideas generated by the pod community and not directed by the PIs.

Through data collected by our external evaluator, we have found that a flat power structure empowers our community, including our steering committee and program participants. For example, our steering committee has education experts and graduate students working together to help mold the BioTAP program. By providing an inclusive environment in which everyone’s voice, regardless of academic hierarchy location or power level, is heard, people of varied experiences can become involved, contribute to improving BioTAP, and ultimately improve GTA TPD. All members of the network can contribute to the advancement of BioTAP with the core acting as facilitators and a goal for the decision-making to become more multi-directional and diffuse over time.

Model Layer 4—Growing and Sustaining the Network: The final layer of our model involves connecting outwards to build the network and learn from others, forming new partnerships, and securing adequate resources to sustain the work. Reaching out of the existing network boundaries to bridge to other groups is important not just for effecting change but also for seeking sustainability resources.

We use the listserv, website, and a yearly virtual conference to link our efforts to departments, universities, and other national organizations. BioTAP’s listserv of over 250 members includes BioTAP PIs, steering committee members, BioTAP Scholars, an evaluator, and other interested stakeholders. The BioTAP website (https://biotap.utk.edu) provides resources to support GTA TPD research including research articles, methods guides, and GTA-specific research instruments; this website will be sustained long after funding for the project has ceased. The website also hosts videos produced by nationally-recognized biology education researchers from the University of Georgia sponsored by their institutional CIRTL (Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning). To date, BioTAP PIs and Scholars have over 15 national presentations and three peer-reviewed publications.

To connect outward, we distribute a letter to BioTAP Scholar supervisors and administrators that includes an explanation of the program as well as a position statement on the value of GTAs as instructors and need for enhanced GTA TPD. We believe that this statement calls attention to the importance of GTA TPD at higher administrative levels. In addition, we have connected with other networks, such as CIRTL, to strengthen the quality of GTA TPD research. The BioTAP community has also hosted two highly-successful virtual conferences. The conferences enable Scholars and others interested in GTA TPD to present their original research to a larger audience and have attracted over 150 attendees from all over the United States and at least three different countries.

Connections to people outside of BioTAP position the network for advocacy on behalf of GTA TPD but rest on the assumption that members have the ability to be advocates within their units. In fact, this may not be the case and presents a significant challenge for any Research Coordination Network whose individuals work in isolation (particularly if these individuals are not powerful or influential within the academic system, such as laboratory coordinators or postdocs). Making connections with institutional advocates who have the ability to make change happen is important to the success of a network comprised of isolated institutional members and a goal for national reform. The administrative letters we send help validate the time and effort of our Scholars and potentially give them a stronger voice in their institutional contexts. These connections also help us seek additional funding and human resources that will support our sustainability and impact on the community.

4 Conclusions

BioTAP seeks to effect cross-institutional change through the power of an RCN-UBE network. Previously, there has been little guidance about how networks such as these can affect institutional change. Building networks involves developing connections between individuals and strengthening those connections over time. We put forward our theory of change for BioTAP as one idea that others may consider as they leverage similar projects. While there is no single “best” potential model to inform a theory of change, the Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan (2016) model has helped us to understand how some elements can differentially help us achieve our outcomes, and which of our assumptions have been erroneous.

We have effectively built a network focused on GTA TPD research, as we envisioned. However, we have faced challenges in enacting collaborative research projects between institutions, mainly because each institution’s TPD program(s) is unique in structure. This often means that researchers have different questions they want to explore or that settling on common measurable outcomes is difficult. We now understand that we may not necessarily produce cross-institutional research collaborations from this iteration of the project, but we can foster collaborations between people that build agency for conducting research in some stakeholders who may not currently have that agency.

In the beginning, we envisioned BioTAP Scholars as institutional and cross-institutional change agents able to communicate at multiple academic levels. Some of them did become change agents in their institutions, either through impacts on their own GTA TPD programs or influencing broader institutional practices. However, most are not in a position to be change agents because of their more marginalized status (e.g., graduate students or postdocs) within the hierarchical structure of academia. Nevertheless, with our support, BioTAP Scholars can still be ambassadors for GTA TPD by publishing or presenting their research, or raising awareness at their institutions. In this way, their BioTAP work could be a conduit for change at other institutions, even if they are not effecting change at their own institutions.

We have also found that it is difficult to connect outwards to other organizations to effect change. Every project tends to have their own focus on GTA TPD in their own context, thus it can be hard to find points of overlap in the missions of each group. In the case of GTA TPD, CIRTL, disciplinary societies, and organizations such as the POD Network would have logical overlap in terms of GTA professional development, but need to find a common effort to justify the extra time it would take to collaborate.

In essence, BioTAP is a network of isolated individuals as well as a national change organization. It is comprised of people who individually may have little power at their institutions, but who have the potential to improve the professional development of graduate students. When banded together as a collaborative organization, the group can consolidate efforts and effect change that is scalable to multiple hierarchical academic systems. This may mean common approaches to GTA TPD at multiple institutions or collaborative research projects are necessary to identify improved teaching practices. These changes depend on strong collaborations, focused on common goals, as well as creating connections to other organizations who can support our efforts. Our project has focused on strengthening those connections such that individuals have strong support networks to be able to take more risks and potentially effect change in GTA TPD at multiple levels within their own complex academic contexts.

5 Acknowledgements

BioTAP was funded by a Research Coordination Network grant from the National Science Foundation (DBI 1539903). We gratefully acknowledge all members of the BioTAP network for their commitment to Biology GTA TPD.

6 About the Authors

Grant Gardner is an Associate Professor of Biology and Graduate Research Faculty in the Interdisciplinary Mathematics and Sciences Education Ph.D. program at Middle Tennessee State University.

Judith S. Ridgway is an Assistant Director at the Center for Life Sciences Education at The Ohio State University.

Elisabeth Schussler is a Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Kristen Miller is an Academic Professional and the Director of the Division of Biological Sciences as the University of Georgia.

Gili Marbach-Ad is the director of the Teaching and Learning Center (TLC) in the College of Computer, mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland.

7 References

American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2011). Vision and change in undergraduate biology education: A call to action. American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://live-visionandchange.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Revised-Vision-and-Change-Final-Report.pdf

American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2015). Vision and change: Chronicling change, inspiring the future. American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://live-visionandchange.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/VISchange2015_webFin.pdf

Anderson, W. A., Banerjee, U., Drennan, C. L., Elgin, S. C. R., Epstein, I. R., Handelsman, J., Hatfull, G., Losick, R., O’Dowd, D. K., Olivera, B. M., Strobel, S. A., Walker, G. C., & Warner, I. M. (2011). Changing the culture of science education at research universities. Science, 331(6014), 152–153. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198280

Austin, A. E., Connolly, M. R., & Colbeck, C. L. (2008). Strategies for preparing integrated faculty: The center for the integration of research, teaching, and learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 113, 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.309

Brancaccio-Taras, L., Gull, K. A., & Ratti, C. (2016). The science teaching fellows program: a model for online faculty development of early career scientists interested in teaching. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 17(3), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v17i3.1243

Connolly, M. R., Lee, Y. G., & Savoy, J. N. (2018). The effects of doctoral teaching development on early-career STEM scholars’ college teaching self-efficacy. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 17(1), ar14. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-02-0039

Eddy, S. L., & Hogan, K. A. (2014). Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-03-0050

Ebert-May, D., Derting, T. L., Henkel, T. P., Middlemis Maher, J., Momsen, J. L., Arnold, B., & Passmore, H. A. (2015). Breaking the cycle: Future faculty begin teaching with learner-centered strategies after professional development. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(2), ar22. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-22-0222

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Love Stowell, S. M., Churchill, A. C., Hund, A. K., Kelsey, K. C., Redmond, M. D., Seiter, S. A., & Barger, N. N. (2015). Transforming graduate training in STEM education. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 96(2), 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9623-96.2.317

Pfund, C., Miller, S., Brenner, K., Bruns, P. J., Chang, A., Ebert-May, D., Fagen, A. P., Gentile, J., Gossens, S., Khan, I., Labov, J. B., Pribbenow, C. M., Susman, M., Tong, L., Wright, R. L., Yuan, R. T., Wood, W. B., & Handelsman, J. (2009). Summer institute to improve university science teaching. Science, 324(5926), 470–471. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170015

Reeves, T. D., Marbach-Ad, G., Miller, K. R., Ridgway, J., Gardner, G. E., Schussler, E. E., & Wischusen, E. W. (2016). A conceptual framework for graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(2), es2. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-10-0225

Reinholz, D. L., & Andrews, T. C. (2020). Change theory and theory of change: What’s the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education, 7(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-0202-3

Rincón-Gallardo, S., & Fullan, M. (2016). Essential features of effective networks in education. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 1(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-09-2015-0007

Schussler, E. E., Read, Q., Marbach-Ad, G., Miller, K., & Ferzli, M. (2015). Preparing biology graduate teaching assistants for their roles as instructors: An assessment of institutional approaches. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(3), ar31. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-11-0196

Stains, M., Harshman, J., Barker, M. K., Chasteen, S. V., Cole, R., DeChenne-Peters, S. E., Eagan Jr., M. K., Esson, J. M., Knight, J. K., Laski, F. A., Levis-Fitzgerald, M., Lee, C. J., Lo, S. M., McDonnell, L. M., McKay, T. A., Michelotti, N., Musgrove, A., Palmer, M. S., Plank, K. M., … Young, A. M. (2018). Anatomy of STEM teaching in North American universities. Science, 359(6383), 1468–1470. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8892

Sundberg, M. D., Armstrong, J. E., & Wischusen, E. W. (2005). A reappraisal of the status of introductory biology laboratory education in U.S. colleges & universities. The American Biology Teacher, 67(9), 525–529.