14 A Department-Level Cultural Change Project: Transforming the Evaluation of Teaching

Noah Finkelstein, Andrea Follmer Greenhoot, Gabriela Weaver, and Ann E. Austin

1 Introduction

Promoting widespread use of evidence-based educational practices (EBEPs) is an important and continuing challenge across higher education institutions. Increasing the use of EBEPs requires explicit support and reward for faculty who embrace these practices, through methods of evaluating teaching that align with research on teaching and learning and that recognize the many facets of teaching. However, few universities employ such approaches to evaluation, usually relying instead on student surveys about their experiences, which focus on a narrow range of teaching practices and have been criticized for bias and other limitations (Stroebe, 2016; Uttl, 2016). Changing the processes for evaluating teaching can contribute to efforts to encourage the use of more effective teaching practices and support greater institutional commitment to high-quality teaching. A key to such cultural change is to focus on the department, given these are the primary units for faculty evaluation at most universities and the units in which faculty see themselves as having the greatest influence (Tagg, 2012, and each of the chapters in this section).

This chapter describes a coordinated approach to fostering change in teaching evaluation processes at the department level, with a focus on strategies that support departmental engagement in change. We draw on our experiences in a multi-institutional project, TEval, that is being carried out at a cluster of three public, research-intensive universities (TEval, n.d.). The TEval approach centers around department-level adaptation and use of a research-based framework that helps departments define and document the elements of teaching effectiveness. A central unit supports departments’ adaptation, implementation, reflection and improvement of the system, and fosters communication and collaboration with other stakeholders and university leaders.

The cluster of three universities collaborating in this project constitute a networked improvement community (NIC) (Bryk et al., 2015), engaged together in an action research paradigm. Organizations that collaborate in taking an NIC approach share a clearly defined goal, develop a common understanding of the problem, test innovative approaches to handling the problem across diverse contexts, engage in rapid iteration, adaptation, and adjustment within each context, compare experiences and results, and learn from consideration of overall patterns and findings. Informed by principles of the NIC model, the three universities involved in the TEval project share a commitment to developing more holistic approaches to teaching evaluation that align with evidence-based teaching practices. They are each implementing a common rubric, while adapting the form and use of the rubric to their local institutional contexts, and tracking and comparing results to produce new insights and discoveries. Leaders and faculty participants from each campus regularly share experiences and results with colleagues from the other campuses at cross-campus knowledge exchanges. A cross-institutional case study is examining the process of transformation within and across the three campuses, focusing on what approaches work most effectively under what circumstances.

The primary purpose of this chapter is to introduce an NIC-based approach to transforming teaching evaluation. Since institution-level change is a time-consuming process, the departments involved in the project overall are still relatively early in implementation of the plans they have developed. Thus, in this chapter, we describe the common framework and related evaluation rubric (Section 2), as well as outline a set of common processes and commitments for helping departments contextualize and implement the framework (Section 3). Next, we provide brief descriptions of how these processes are being implemented at three campuses, allowing attention to different contexts as consistent with the principles of NICs (Section 4). Our on-going cross-institutional research and periodic Knowledge Exchanges that bring together leaders from across the institutions are enabling us to compare processes and begin to identify emerging lessons. In the final section, we offer some emerging (but still developing) observations based on the common and distinct approaches to promoting departmentally-based improvement of teaching evaluation taken by the participating universities (Section 5).

2 Our Common Framework

The evaluation approaches being advanced are based in a common framework that draws on 25 years of work on scholarly teaching and its evaluation (Bernstein & Huber, 2006; Glassick et al., 1997; Hutchings, 1995, 1996; Lyde et al., 2016) and related work on the peer review of teaching (see Bernstein, 2008). The framework for our approach provides a richer, more complete view of teaching practice and the evidence that speaks to it than most commonly used measures (Dennin et al., 2017; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2020a). The framework specifies that multiple dimensions of teaching activities should be evaluated, to capture the teaching endeavor in its totality, including aspects that take place outside of the classroom and that go beyond the teaching of individual courses. Table 1 shows the dimensions of the framework that are currently being enacted across the change effort. The seven dimensions are designed to span the full array of teaching activities (inside and out of the classroom) with equity and inclusivity as a theme running across all of the dimensions.

| Teaching Dimension* | Description/Guiding Questions |

| Goals, content, and alignment

|

What are students expected to learn from the courses taught? Are course goals articulated and appropriate? Is content aligned with the curriculum? Are topics appropriately challenging and related to current issues in the field? Are the materials high quality and aligned with course goals? Does content represent diverse perspectives? |

| Teaching practices

|

How is in-class and out-of-class time used? What assignments, assessments, and learning activities are implemented to help students learn? to: Are effective and inclusive methods being used to support learning in all students? Do in and out of class activities provide opportunities for practice and feedback on important skills and concepts? Are students engaged in the learning process? Are assessments and assignments varied, enabling students to demonstrate knowledge through multiple means? |

| Achievement of learning outcomes

|

What impact do these courses have on learners? What evidence shows the level of student understanding and how does it inform the instructor’s teaching? Are standards for evaluating students connected to program or other expectations? Are there efforts to support learning in all students and reduce inequities? Does learning support success in other contexts (e.g., later courses)? |

| Class climate | What sort of climate for learning does the faculty member create? What are the students’ views of their learning experience and how has this informed the faculty member’s teaching? Is the classroom climate respectful, inclusive, and cooperative? Does it encourage student motivation, efficacy, and ownership? Does the instructor model inclusive language and behavior? |

| Reflection and iterative growth

|

How has the faculty member’s teaching changed over time? How has this been informed by evidence of student learning and student feedback? Have improvements in student learning or improved equity been shown, based on past course modifications? |

| Mentoring and advising | How effectively has the faculty member worked individually with undergraduate or graduate students? How does the quality and time commitment to mentoring fit with disciplinary and departmental expectations? |

| Involvement in teaching service, scholarship, or community | In what ways has the faculty member contributed to the broader teaching community, both on and off campus? Is the instructor involved in teaching-related committees, curriculum or assessment activities? Does the faculty member share practices or teaching results with colleagues? |

*Note: These dimensions are drawn from the Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness Framework (Follmer Greenhoot, Ward, Bernstein, Patterson, & Colyott, 2020).

The framework also specifies that multiple lenses (sources and types of data) should be used, including faculty self-report (e.g., course materials, evidence of students learning and reflections on it), peer/outside reviews (e.g., class visits, review of course materials), and student voices (e.g., student surveys, alumni letters, focus groups). Information from these sources, moreover, should be triangulated to provide convergent evidence on multiple categories of teaching activities. Each campus has operationalized this framework as a rubric, with guiding questions for each dimension and descriptions of different quality tiers of each one (ranging from novice to professional). These descriptions of different levels of performance provide scaffolding and feedback to improve teaching while also structuring the evaluation process.

The framework is designed to bring greater attention to the full range of activities that comprise teaching, to promote more serious consideration of multiple sources of information that speak to teaching effectiveness, to bring greater structure, consistency and validity to teaching evaluation, and to promote processes that support teaching improvement as well as evaluation. The framework is designed to be a starting point for department-level conversations.

3 Processes and Commitments to Change

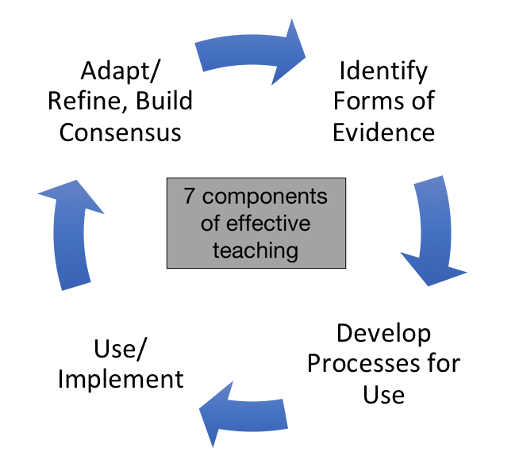

As noted, the three campuses are enacting common processes, commitments and theories of change to support departments in using the framework to design and implement new approaches for teaching evaluation. A central unit on each campus guides departments through the cycle shown in Figure 1, to contextualize the framework (the rubric language and possible evidence for each dimension) to local disciplinary culture, implement it, and refine it based on results and lessons learned. For example, specific approaches for what counts as and how to measure student learning are likely different in history and physics, and these units are supported in identifying appropriate data sources, measures and processes. Further, the relative weighting of each dimension of effective teaching may vary by discipline. For example, some disciplinary units may value mentoring and advising more than others. All departments are asked to use information gathered from the self-report, peer review, and students, but also are encouraged to identify the combination of evidence and artifacts from these sources most appropriate for them. This approach provides the university with a common approach and language around teaching evaluation while preserving disciplinary identity and specificity.

In facilitating departmentally-based work, we draw from models of change that employ a bottom-up and top-down approach meeting a middle-out approach for change (Reinholz et al., 2015). In the bottom-up approach, departmental working groups of individual faculty are supported by the centralized transformation effort to identify specific tools and processes that address the benchmarks for teaching effectiveness described in section one. Recognizing the critical role of top-down support, the campus-based change initiative connects the departmentally-based work with institutional leadership and its processes and priorities for teaching evaluation. For example, in the UMass description below, the departmentally based work is aligned with goals and priorities of both the faculty union and the Office of the Provost. At Colorado and Kansas, the department work supports the faculty governance’s calls to move away from student rating systems (e.g., Boulder Faculty Assembly [BFA], 2018) while fulfilling the Regents mandate for a student rating system. Applying a middle-out approach, each campus has its locus of action in department-wide discussion and adoption of the improved tools and processes developed by in-house working groups. Furthermore, the projects support cross-departmental sharing of the specific tools, approaches, challenges and solutions for improving teaching evaluations.

The project holds core commitments to change, which support campus-wide and cross-campus cohesion. The commitments of this project include the following principles:

- Voluntary engagement—all units are welcomed but not required to participate in change

- Scholarly approaches—wherever possible, disciplines draw from evidence-based tools and processes and appropriate theories of change (ASCN, 2020 and chapters in this section).

- Disciplinary-definition—departments define their specific approaches.

- Common-structure—while locally enacted, a common framework applies to all units.

- Balancing formative and summative approaches—teaching evaluation should serve to improve education and to provide final evaluation of effectiveness.

- Continuous improvement—both the instructors and departments are continually refining teaching practices and evaluation of teaching.

- Learner-facing and Inclusive—ultimately, all units should support students, with particular attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

4 Implementation at Three Sites

4.1 University of Colorado Boulder

The University of Colorado Boulder (CU-B) approach, the Teaching Quality Framework Initiative (TQF, n.d.), presented in more detail in a case study (Andrews et al., this volume) was seeded by the Association of American Universities (AAU)’s STEM Education Initiative. The project includes three categories of stakeholders. TQF-central (a team of individuals housed in the Center for STEM Learning) manages the overall project, supports departmental engagement and contextualization of the framework, builds campus-wide community across all stakeholders, and coordinates with the administrative and institutional stakeholders to ensure campus wide support and alignment. Departments are facilitated using a Departmental Action Team (Corbo et al., 2016) approach, to contextualize the framework to local disciplinary culture, to establish processes for enacting evaluation, and to link these to departmental policies and structures. Campus-wide and administrative stakeholders include the associate provosts, deans, the faculty assembly, institutional research, information technology, the student council, and other campus groups committed to enhancing educational practice and faculty evaluation.

Departments engaged in three phases for enacting change. Phase 1 identifies department-wide interest, and includes departmental representatives in the campus-wide stakeholder meetings. Phase 2 identifies a working group of faculty, associated processes, and reward structures for the group. Phase 3 is a roughly year-long process where the departmental working team engages in facilitated discussions to identify appropriate forms of data, improved rating systems, observation protocols, etc. The working group also defines the processes and policies for enacting the new teaching evaluation system and where it applies (i.e. in annual merit and/or comprehensive review and tenure). For an example of departmentally based approaches to using the rubric, see materials in Teaching Quality Framework Initiative (n.d.).

Each semester, there are opportunities to share materials and approaches across disciplinary units. Additionally, once or twice per semester, a campus-wide stakeholder group gathers to align the disciplinary-based efforts with each other to campus priorities and resources. As of May 2020, 19 units were involved across three colleges: Arts and Sciences (A&S), Engineering, and Business. Eight departments have participated in the phase 3 process, creating new tools and processes for evaluating teaching in their units. The TQF initiative also partners with the Boulder Faculty Assembly to address calls for improved teaching evaluation (BFA, 2018), and the Office of Institutional Research piloting a new student evaluation of teaching (SET) rating system and new models for representing and using these SET data. Each of the colleges (A&S, Engineering, and Business) has provided support to fund staff at TQF-Central to enact change in their units, and have or are developing statements of commitment to enhanced teaching evaluation that align with the TQF approach.

4.2 University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) effort, Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness, is led out of KU’s Center for Teaching Excellence (CTE). University policy already requires multiple sources of information for teaching evaluation, therefore the primary focus of the KU project is on developing structures, procedures, and expectations that support more meaningful implementation of the policies. The effort began in 2015 when the CTE developed the Benchmarks rubric (Greenhoot et al., 2020) in response to growing faculty dissatisfaction with teaching evaluation practices, along with widening faculty participation in educational transformation. The Benchmarks rubric was built on a model of teaching as inquiry (e.g., Bernstein, 2008) that had guided CTE programs for years; the rubric translated those ideals into transparent expectations about effective teaching and was refined through broad input from stakeholders, including department chairs, CTE department ambassadors, and departments that piloted it for peer review of teaching.

As the hub of KU’s TEval implementation, the CTE supports departments in carrying out the iterative process illustrated in Figure 1, while also collaborating with university leadership and governance structures to move towards institutionalization of a transformed approach. To ensure readiness and broad engagement, departments are selected through a competitive proposal process that prioritizes clear support from the department chair and broad faculty participation. Departments identify a project leader and a team of three or more faculty members to carry out the work. The CTE supports department-level work through a) mini-grant funds, b) monthly consultations with a CTE faculty leader, c) examples, templates, tools, and other resources (see materials in TEval, n.d.), and d) convening a cross-department working group that meets about twice a semester to share strategies, results, and lessons. Department teams produce a report each semester, and present their work at campus events/workshops. The goal is to provide accountability, generate artifacts for analysis by the PIs, give visibility to the work, and create models for other departments.

To date, 12 STEM and non-STEM departments in three cohorts have adapted and used the rubric and built consensus around it. Although all departments are working towards use of the rubric for promotion and tenure (P&T) evaluations, they vary in their starting points. Some have already implemented it in the P&T context (for department-level evaluation, or peer- or self-reviews that become part of the P&T package), whereas others are first using it in lower-stakes or formative settings, such as mentoring of pre-tenure faculty or peer-review “triads.”

The CTE has also worked with administrators to align new requirements, recommendations, and infrastructure (e.g., requirements for the timing and quality of peer reviews, an online system for annual evaluation of contingent faculty and teaching professors) with the ideals embedded in the Benchmarks framework, and advocate the Benchmarks rubric as a tool for completing required processes. Additionally, participants and leaders in the Benchmarks initiative are serving on steering committees charged by the Provost Office and Faculty Governance to reconsider P&T guidelines on teaching and appropriate uses of student ratings.

4.3 University of Massachusetts, Amherst

The TEval project at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst (UMass) is a collaboration between the Office of Academic Planning and Assessment (OAPA) and the educational initiatives area of the Office of the Provost. The effort resulted from a task force review of external research about and processes for teaching evaluation, resulting in an internal white paper with recommendations for the UMass community. That task force was co-led by the directors of the OAPA and the UMass Center for Teaching Excellence and Faculty Development (TEFD), and its work preceded the funding of TEval by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The team recommended expanding campus approaches to teaching beyond student evaluations and that a model based on the KU Benchmarks work be adapted and implemented at UMass.

The TEval partnership with KU and CU-B allowed UMass to leverage the work that its task force had done and take action on recommended next steps with the funding provided by NSF. Each year of the first three years of TEval, the UMass leadership team selected departments from among those applying to participate in adapting and implementing a form of the Benchmarks rubric. The applications submitted for participation needed to demonstrate the department’s commitment to expanding their approach to teaching evaluation, describe how the effort would be a department-wide one, and be co-led by the Head or Chair in addition to one or more faculty members. By supplementing NSF funding with funding from the Office of the Provost, departments from both STEM and non-STEM disciplines have been included in each of the three cohorts. To date, nine departments (four non-STEM, five STEM), representing four Colleges (Public Health and Health Sciences; Information and Computer Sciences; Humanities and Fine Arts; Natural Sciences) are involved.

One or two members from each participating department attend bi-weekly cross-departmental meetings with the project leadership team. These meetings allow for exchange of information between the leadership team and the participating departments, as well as among faculty from different departments. Importantly, these regular meetings serve to establish a learning community among those engaged in the process of transforming their departmental approach to the evaluation of teaching. The leadership team also meets with each participating department individually at least once per semester. If a department requests them, additional support or meetings are also arranged. Departments that began the project as part of the first cohort are still involved, which has allowed a natural peer-mentoring dynamic to emerge, while the multidisciplinary nature of the group cross-fertilizes ideas among participants.

The engagement of upper-level administration in the UMass effort has proven vital in maintaining forward momentum for the work. The initial task force was launched with support of the Provost, and the NSF-supported work has been reported at regular intervals to that office. In addition, leaders of the faculty union at UMass have been informed of the efforts from the time the task force white paper emerged. Engagement of these two groups has recently resulted in new wording being negotiated for the faculty contracts, which requires multiple sources of information being considered for teaching evaluation. While faculty have expressed a desire for evaluation methods beyond just student surveys, the effort required to integrate new approaches into the normal operations of departments involves time and work that many participants had not

anticipated. Their dedication to date has been buoyed by the knowledge that the work may result in a template for campus-wide change, and that it is being supported by both the faculty union and the administration. Similarly, those changes would likely not be embraced if they were dictated from above rather than nurtured from within.

5 Lessons Learned and Next Steps

In addition to guiding the work within and across each of the three participating institutions, we are also conducting cross-institutional research to learn from our cases about initiating and advancing institution-level efforts to reform approaches to teaching evaluation. We are using site visits, interviews, focus groups, document review, and conversations among institutional leaders at the Knowledge Exchanges as strategies for engaging in the cross-institutional comparisons and reflections that are elements in how NICs learn. At this point in our project, we can offer some emerging observations and lessons, but much remains to be learned as the departments more fully implement and adapt their use of the rubric. The three institutions engaged in the project have some distinctive contextual differences; for example, institutional leadership for the project is located in different places at each institution, and one has a faculty union. Also, each department involved has chosen its own approach to using the rubric. Some, for example, have decided to begin with careful consideration of the elements of the rubric and adaptation of each element to specific disciplinary needs, while others have been willing to accept the dimensions of the rubric with little change. Use of the rubric is a relatively slow process in most cases, with small groups of faculty choosing to experiment by applying it to specific faculty processes as starting points for attracting broader attention, interest, and buy-in from their colleagues.

Starting points for applying the rubric typically fall in one of the following areas: as a guide for mentoring early career colleagues; as a framework for classroom observations and peer reviews and discussions about teaching; as a framework for a required or optional self-reflection statement in an annual review or promotion packet; or as a guide for discussion topics in graduate student professional development. Departments’ choices of starting points seem to relate to the interests of the faculty leaders and their perceptions of where they may get the most traction for testing and demonstrating the usefulness and relevance of the rubric to their departmental context.

We have seen a set of common challenges or barriers across the participating institutions and departments. These include a sense of uncertainty as to where to start; that is, interest in using the rubric is sometimes greater than strategic knowledge of how to begin a change effort. For many faculty members, the time they perceive that will be needed to experiment with or apply the rubric in various ways is a major barrier, thwarting progress. In other cases, some faculty with strong teaching orientations invest time but find that they struggle to get attention and commitment to use of the rubric from more senior colleagues or the departmental chair. Now two years into the project, we also have seen examples of loss of momentum when supportive department chairs or highly invested faculty colleagues depart. Probably the strongest, as well as most frequent, challenge is lack of wide commitment and buy-in across a department.

We also are using the NIC approach to compare the implementation of innovations across contexts to begin to deduce a set of strategies that facilitate change toward transformation in teaching evaluation. We highlight a few of these strategies here, while noting that transformational organizational change in higher education requires patience. The process of developing, testing, and implementing strategies for using the rubric and transforming departmental cultures is getting a foothold but still in the developmental stages in most of the departments. Some of the important strategies to initiate change around teaching evaluation include assessing relevant features of the institutional landscape and then developing and articulating a narrative about how thoughtful teaching evaluation relates to institutional priorities and history. Another strategy includes finding ways to attract and sustain the interest of recognized leaders within the department as well as finding champions at the departmental, college, or institutional levels. Identifying allies whose own interests and goals align with the project of reforming teaching evaluation can also be useful. As the departments continue their work of refining the rubric for their situations and finding ways to implement and integrate it into their collective and individual work, we will continue to observe and analyze the processes they follow and issues they confront.

Interest in new approaches to teaching evaluation is growing across the U.S. (and beyond). The project has its roots in the Bay View Alliance (n.d.), and, as the initiative continues, the team is connecting its work with national initiatives focused on teaching evaluation that are emerging at the National Academies’ Roundtable on Systemic Reform on STEM Undergraduate Education (NASEM, 2020b) and the AAU (AAU, n.d.). The TEval website (TEval, n.d.) provides up-to-date information on these developments.

6 Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported, in part, by the NSF, Award numbers: DRL 1725946, 1726087, 1725959, and 1725956. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

TEval is a multi-institution initiative of the Bay View Alliance, an international network of research universities exploring strategies to support and sustain the widespread adoption of instructional methods that lead to better student learning.

7 About the Authors

Noah Finkelstein is a Professor in the Department of Physics and co-Director of the Center for STEM Learning at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Andrea Follmer Greenhoot is Professor of Psychology, Director of the Center for Teaching Excellence, and Gautt Teaching Scholar at the University of Kansas.

Gabriela Weaver is a Professor of Chemistry at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Ann E. Austin is the Associate Dean for Research in the Department of Educational Administration at the University of Michigan.

8 References

Association of American Universities (n.d.). Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/education-community-impact/undergraduate-education/undergraduate-stem-education-initiative-3

Andrews, S. E., Keating, J., Corbo, J. C., Gammon, M., Reinholz, D. L., & Finkelstein, N. (this volume). “Transforming teaching evaluation in disciplines: A model and case study of departmental change.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 13). Pressbooks.

Accelerating Systemic Change Network (n.d.). Working Group 1: Guiding Theories. Accelerating Systemic Change Network. https://ascnhighered.org/ASCN/guiding_theories.html

Boulder Faculty Assembly. (2018). Best practices—Moving beyond the FCQ. University of Colorado Boulder, College of Media, Communication, and Information. https://www.colorado.edu/cmci/sites/default/files/attached-files/beyond_the_fcq_best_practices_draft_10.24.18.pdf

Bernstein, D. (2008). Peer review and evaluation of the intellectual work of teaching. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 40(2), 48–51. http://doi.org/10.3200/CHNG.40.2.48-51

Bernstein, D., & Huber, M. T. (2006). What is good teaching? Raising the bar through Scholarship Assessed [presentation]. International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Washington, D.C.

Bryk, A., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., & LeMahieu, P. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Harvard Education Press.

Bay View Alliance (n.d.). Evaluating teaching: Transforming the evaluation of teaching. Bay View Alliance. https://bayviewalliance.org/projects/evaluating-teaching/

Corbo, J. C., Reinholz, D.L., Dancy, M.H, Deetz, S. and Finkelstein, N. (2016). Sustainable change: A framework for transforming departmental culture to support educational innovation. Physical Review Special Topics—Physics Education Research 12, 010113. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.010113

Dennin, M., Schultz, Z. D., Feig, A., Finkelstein, N., Greenhoot, A. F., Hildreth, M., Leibovich, A. K., Martin, J. D., Moldwin, M. B., O’Dowd, D. K., Posey, L. A., Smith, T. L., & Miller, E. R. (2017). Aligning practice to policies: Changing the culture to recognize and reward teaching at research universities. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(4), es5. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-02-0032

Greenhoot, A. F., Ward, D., Bernstein, D., Patterson, M., & Colyott, K. (2020). Benchmarks for teaching effectiveness rubric. The University of Kansas Center for Teaching Excellence. https://cte.ku.edu/rubric-department-evaluation-faculty-teaching

Gardner, G., Ridway, J., Schussler, E., Miller, K., & Marbach-Ad, G. (this volume). “Research coordination networks to promote cross-institutional change: A case study of graduate student teaching professional development.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 10). Pressbooks.

Glassick, C. E., Huber, M. T., & Maeroff, G. I. (1997). Scholarship assessed: Evaluation of the professoriate. Special Report. Jossey Bass Inc.

Hutchings, P. (Ed.). (1995). From idea to prototype: The peer review of teaching. Stylus.

Hutchings, P. (Ed.). (1996). Making teaching community property: A menu for peer collaboration and peer review. Stylus.

Kezar, A., & Miller, E. R. (this volume). “Using a systems approach to change: Examining the AAU Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 9). Pressbooks.

Lyde, A.R., Grieshaber, D.C., & Byrns, G. (2016). Faculty teaching performance: Perceptions of a multi-source method for evaluation (MME). Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 16(3), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v16i3.18145

Marbach-Ad., G., Hunt, C., & Thompson, K. V. (this volume). “Using data on student values and experiences to engage faculty members in discussions on improving teaching.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 8). Pressbooks.

Margherio, C., Doten-Snitker, K., Williams, J., Litzler, E., Andrijcic, E., & Mohan, S. (this volume). “Cultivating strategic partnerships to transform STEM education.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 12). Pressbooks.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020a). Recognizing and evaluating science teaching in higher education: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25685

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2020b). Roundtable on systemic change in undergraduate STEM education. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/BOSE/systemic_change_in_Undergrad_STEM_Education/index.htm

Reinholz, D. L., Corbo, J. C., Dancy, M. H., Deetz, S., and Finkelstein, N. (2015). Towards a Model of Systemic Change in University STEM Education. In G. C. Weaver, W. D. Burgess, A. L. Childress, and L. Slakey (Eds.), Transforming institutions: 21st century undergraduate STEM education (pp. 115–124). Purdue University Press

Stroebe, W. (2016). Why good teaching evaluations may reward bad teaching: On grade inflation and other unintended consequences of student evaluations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(6), 800–816. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616650284

Tagg, J. (2012). Why does the faculty resist change? Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 44(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2012.635987

TEval. (n.d.). Transforming higher education—Multidimensional evaluation of teaching. TEval.net. https://teval.net

Teaching Quality Framework Initiative. (n.d.). Teaching Quality Framework Initiative. University of Colorado Boulder. https://www.colorado.edu/teaching-quality-framework/

Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Gonzalez, D. W. (2016). Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.007

Wojdak, J., Phelps-Durr, T., Gough, L., Atuobi, T., DeBoy, C., Moss, P., Sible, J., & Mouchrek, N. (this volume). “Learning together: Four institutions’ collective approach to building sustained inclusive excellence programs in STEM.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 11). Pressbooks.