15 Moving toward Greater Equity and Inclusion in STEM through Pedagogical Partnership

Alison Cook-Sather, Helen White, Tomás Aramburu, Camille Samuels, and Paul Wynkoop

1 Introduction

Traditional equity and inclusion efforts concentrate on helping students navigate and succeed within existing institutional norms and practices. Pedagogical partnerships have the potential both to support students in such navigation and to position them to draw on their experiences, identities, and knowledge to challenge and change those norms and practices (de Bie et al., 2019). By “pedagogical partnership,” we mean “a collaborative, reciprocal process” through which participants “contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualization, decision making, implementation, investigation, or analysis” (Cook-Sather et al., 2014, pp. 6–7). Pedagogical partnerships can inspire deepened engagement, raised awareness, and enhanced experiences of teaching and learning for student and faculty partners (Cook-Sather et al., 2014; Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017). Particularly relevant to this discussion, they can also contribute to the creation of more culturally responsive and inclusive practices (Cook-Sather, 2019; Cook-Sather & Agu, 2013; Cook-Sather & Des-Ogugua, 2018) through recognizing historically underrepresented and under-served students in particular as “holders and creators of knowledge” (Delgado Bernal, 2002, p. 106) and through making equity and inclusion the focus of all partnership work.

This paper offers four examples of how student-faculty partners lead change toward more equitable and inclusive practices in STEM through pedagogical partnership at Haverford College. A selective, liberal arts college in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, Haverford enrolls 1,353 students, 42.5% students of color and 14% international students, and supports 50% of students with some form of financial aid. Self-described as highly rigorous, the college has recently recognized that its “rigor-first” approach privileges some students over others, particularly in STEM. In Astronomy, Physics, Mathematics, and Computer Science (but not Biology or Chemistry), numbers of both underrepresented students and female-identifying students decrease between the first and second semesters and into the second year. Furthermore, students perceive introductory science classes as “weed-out” courses, and underrepresented students interested in STEM are advised by peers to avoid introductory science courses because of the negative classroom culture and insufficient support structures.

Since 2007, Haverford has co-sponsored with Bryn Mawr College the Students as Learners and Teachers (SaLT) program through which more than 290 faculty and 195 students have participated in over 400 pedagogical partnerships. The signature program of the Teaching and Learning Institute at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges, SaLT has focused since its advent on developing more inclusive and equitable classroom practices (Cook-Sather, 2018), both through positioning underrepresented students as educational developers (Cook-Sather et al., 2019a) and through making equity and inclusion an implicit or explicit focus of all partnership work (Cook-Sather et al., 2019b).

Supported originally by over $1 million in funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and subsequently by the Provosts’ Offices at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges, the SaLT program supports faculty at any stage in their careers (Cook-Sather, 2016). The student consultants who piloted the program were five students of color, and in each subsequent semester between 50% and 75% of the 195 SaLT student consultants have identified as belonging to one or more of the following equity-seeking groups: African American, Asian American, Latinx, female, first-generation college student, low income, disabled, and/or queer (Cook-Sather, 2019). SaLT supports or informs all the examples we discuss here.

The “we” of this paper is an intentional combination of faculty and students at Haverford College:

- Alison Cook-Sather is a faculty member in the Bryn Mawr/Haverford Education Program and director of SaLT.

- Helen White is a faculty member in the Chemistry and Environmental Studies Departments and director of the Integrated Natural Science Center.

- Tomás Aramburu, class of 2019, majored in chemistry, minored in creative writing, completed a concentration in biochemistry, and was a teaching assistant in the Chemistry Department.

- Camille Samuels, class of 2021, has been a student in White’s courses, and

- Paul Wynkoop, class of 2020, majored in psychology and completed a minor in neuroscience and worked as a SaLT student consultant for three years.

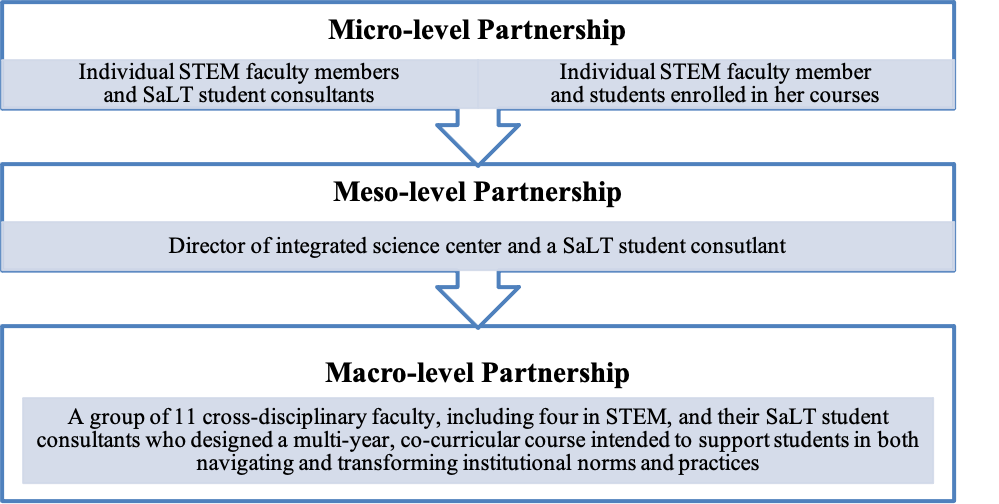

Elaborating on the description of some of the SaLT program work Cook-Sather shared at the ASCN Transforming Institutions Conference (Takayama et al., 2017), we describe four efforts, each at a different stage of maturation, to make pedagogical practices in STEM more equitable and inclusive: two at the micro level, one at the meso level, and one at the macro level. The longest-standing micro-level example has been researched and reported on in numerous publications, some of which are cited here. The other three follow from or build on that example and are in the very preliminary stages of being researched. Figure 1 presents these four examples.

IIn contrast to the successful top-down model of change Halasek et al. (this volume) discuss, this paper offers an example of how change can be effected moving from the micro through the meso to the macros levels.

2 Micro-level Example 1: Faculty Working with SaLT Student Consultants

Of the 290 faculty who have participated in the SaLT program since its advent, 85 have been in a STEM field. Each of them worked in a micro-level pedagogical partnership—a semester-long, one-on-one collaboration or a summer-long collaboration with an undergraduate student positioned as a pedagogical partner—and some continued their partnership work for multiple semesters. All student-faculty pairs receive guidelines for how to develop partnerships (see Cook-Sather et al. [2019b] for the guidelines), although each partnership is unique.

Almost all initial partnerships pay an undergraduate student not enrolled in a faculty member’s course by the hour for the following: observing one session of that course per week, taking detailed observation notes on pedagogical approaches or challenges upon which the faculty partner wants to focus, and then meeting weekly with the faculty partner to discuss what is already contributing to the creation of an equitable and effective learning environment and what might be revised better to meet the needs of a diversity of students. Rather than receiving training prior to embarking on this work, student partners meet weekly in small groups with Cook-Sather and other student partners to develop the language, confidence, and capacity to work in such intellectually and emotionally demanding roles. (See Cook-Sather et al. [2019b] for details regarding how to develop such pedagogical partnership.) This approach shares many of the features of the discipline-based educational specialist model Chasteen et al. (this volume) and Greenhoot et al. (this volume) discuss (e.g., engage in classroom observations, aim for constructive conversations, observe faculty over time) and the peer-observation of teaching model discussed in Salomone et al. (this volume), but it positions students who are not discipline experts in this role.

Cook-Sather has assessed faculty experiences through the SaLT program each semester through asking open-ended questions on anonymous surveys (e.g., What are the most important pedagogical insights you clarified or gained through working with your student partner? How have those informed your practice, and how do they position or prepare you to continue to develop as a teacher?). Also since the program’s advent, she has conducted numerous ethics board-approved research studies on SaLT partnerships focused on both general and equity outcomes.

Furthermore, individual faculty partners have engaged in systematic reflection and published essays on their work with student consultants. These include explorations of how to revise course structure, assignments, and assessments in organic chemistry (Charkoudian et al., 2015), address under-representation and create more inclusive classrooms in physics (Perez, 2016), and make student engagement more active and equitable in astrophysics (Narayanan & Abbot, 2020). Charkoudian found that, after working in partnership, she “consciously created an environment of pedagogical transparency and fostered an environment in which students could come to me with continual feedback and suggestions to make the course stronger” (Charkoudian et al., 2015, p. 8). Perez (2016) found that pedagogical partnerships “create the space necessary to address with students how issues of equity and inclusion affect their classrooms and fields” (p. 4). And Narayanan found his partnership work to be “simply transformative,” supporting him in moving from university systems “where the style was often combative between students and professors” toward “increasing clarity and energy,” which had the effect of “deepening the in-class relationship” between faculty and students and has proven efficacious “in broadening participation and retention of underrepresented minorities in the field” (Narayanan & Abbot, 2020, pp. 193–194).

SaLT student consultants have also analyzed the efficacy of partnership work for student partners and for students enrolled in the faculty members’ courses. Pedagogical partnerships effect transformations in students’ sense of themselves as learners, building awareness, confidence, and capacity (Wynkoop, 2018). Student consultants underrepresented in the sciences report not only “increased sense of confidence and ability to articulate myself (Mathrani 2018)” (Mathrani & Cook-Sather, 2020, p. 162) but also capacity to support faculty in making “students from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds” feel more included (Mathrani & Cook-Sather, 2020, p. 165).

3 Micro-level Example 2: Faculty Working with Enrolled Student Partners

The second form of micro-level partnership work was initiated by students and extended into collaboration with a STEM faculty member, inspired in part by SaLT partnership work. While SaLT has supported and researched faculty-student partnerships for 13 years, this second form of partnership work we present is only recently beginning to unfold because faculty members like White have developed a commitment to working with students as partners. As this work continues to expand, it will be integrated into the various DEI-focused research projects on campus. We share it as one example of how student initiative can intersect with faculty receptivity and commitment to collaborative efforts for equity and inclusion.

Aramburu and Samuels, who had not participated in SaLT, created a student group for underrepresented students in STEM at Haverford College, and contacted White about how, in her role as director of the Integrated Science Center at the college, she might support the group. The initial intention of the student group was to provide mentorship for underrepresented minority students interested in pursuing STEM fields at Haverford with the hope of retaining more underrepresented students in the introductory chemistry sequence/major. In addition, Aramburu and Samuels aimed to reach out to STEM faculty and staff to help publicize the initiative and encourage more underrepresented students to take on roles as TAs and tutors. Over time, the group also formed a student advisory committee to communicate the student experience in STEM courses to faculty, and to provide feedback regarding curricular discussions and changes.

Faculty support for this initiative provided compensation for student leaders, mentors, and tutors associated with the group. Furthermore, the group encouraged underrepresented minority students to take on paid positions as TAs, tutors, and as members of the student advisory group.

The student group, in conversation with faculty partners, recognized the need to highlight and strengthen pathways and opportunities that already exist for students pursuing STEM fields, including peer-tutoring, on-campus research with faculty mentors, off-campus research, and travel to conferences and meetings specifically aimed at underrepresented students (e.g., The Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science National Diversity in STEM Conference). As a result of conversations with Aramburu and Samuels, decisions regarding the funding of research and travel awards to students became need-sensitive so that resources could be better leveraged to support all students.

4 Meso-Level Example: Director of Integrated Science Center Working with a SaLT Student Consultant

Having previously worked in a SaLT partnership with a physics professor, Wynkoop brought experience with striving to support the development of culturally responsive and inclusive practices within STEM courses and was therefore well positioned to look across STEM departments. To begin their partnership focused on work at the meso level, White and Wynkoop analyzed the current discourse surrounding the participation of underrepresented populations in STEM on a broad scale. Using Ferrare and Lee’s (2014) seminal study as their guide, they analyzed the ways in which discourse surrounding the economic vitality of STEM careers and different sociocultural conditions have contributed to gender-, race-, and class-based disparities in STEM. They focused in particular on the finding that, while a wide diversity of students begins their college careers as STEM majors, few from underrepresented groups continue with STEM after their first semester or first year—a failure of what is called “STEM retention” (see Callahan et al., this volume).

As they came to better understand the reasons behind the present homogeneity within STEM, White and Wynkoop shifted their focus from these cross-context findings and zeroed in on the lack of diversity in STEM majors at Haverford College. Keeping in mind the insights from SaLT partnership work and the culturally responsive theory that informs it, they decided that the best step to move forward with conceptualizing the issues in STEM retention was to survey the student body and see who exactly was enrolled in STEM classes across the different class years and what their experiences were. Their purpose was to determine whether Haverford followed the general trend of having a diversity of students enrolling in introductory STEM classes with the intent to major in STEM, followed by a decrease in diversity in students in subsequent courses and majoring in STEM fields, and to try to identify why, in this context.

White and Wynkoop contacted several STEM inclusion groups on campus to get a better sense of the experiences and challenges their members experienced in STEM courses and the various methods the groups had found most effective in empowering and supporting one another in learning and living at Haverford. Considering their conversations with these STEM inclusion groups, White and Wynkoop created surveys to gather students’ experiences in STEM classes, with STEM faculty, and how they considered their own ability in STEM classes.

Through their partnership, Wynkoop and White were able to consider how faculty and student peers can play a role in retention of underrepresented students in STEM. While rooted in the intellectual framework of literature examining the inequalities present in higher education, their conversations provided a space for them to do some of the emotional work that is required to explore and reflect on what they were learning (White & Wynkoop, 2019). Through weekly conversations, White and Wynkoop discussed their relationship to and understanding of the inequalities in higher education. These conversations ranged from descriptions of personal experiences to sharing stories from their peers (faculty and students respectively) to discussing experiences that they had witnessed at Haverford. Honest and direct dialogue between White and Wynkoop, expressed in a supportive framework where the major objectives were to learn and understand, helped them both to move beyond the limits of their own perspectives as professor and student, respectively, as they worked to imagine a change strategy (see Callahan et al., this volume).

Because they exist as people at Haverford in two distinct roles, it would have been easy for them to bring in ideas about how to fix the problem of a lack of underrepresented students in STEM and assume that these ideas were the one and only way to solve the issue at hand. However, both White and Wynkoop took the time to hear one another and work together—along with seeking insight from other students and faculty engaged in conversations about equity and inclusion—to identify the most effective ways forward with the STEM-retention problem.

5 Macro-Level Example: Cross-Disciplinary Faculty Group Designing Co-Curricular Course

The macro-level example we share builds on the micro- and meso-level examples in both process and content. Drawing on the many years of SaLT-supported partnerships and on White’s individual and department-level partnership work, this example illustrates what can happen when a partnership ethos begins to inform institution-wide equity efforts. Supported by the Provost’s Office and multiple centers at Haverford, a group of faculty from Biology, Chemistry, Computer Science, East Asian Languages and Cultures, French, Linguistics, Sociology, and Visual Studies participated in a seminar facilitated by Cook-Sather—a variation on the Cross-course Communities of Transformation approach discussed by Klein et al. (this volume).

This cross-disciplinary group of faculty spent a semester together developing a multi-year, co-created, collaboratively facilitated, mentor structure/peer role model course designed not only to help students navigate the existing departmental norms and practices, such as courses developed by Trinity Washington University and Radford University (Sible et al., 2019), but also on transforming them. Striving also to support transformation and thinking beyond the single-semester model, the group produced a syllabus for a 3- or 4-year, 1 (total) teaching credit assignment for a faculty member and 0.25 course credit per semester for students. The course aims to provide students opportunities to: develop the cultural capital and language of the academic culture of power in order to successfully navigate the institution as it is; affirm and deploy their lived experiences, knowledge, skills, and cultural backgrounds to challenge normative institutional culture and help create a departmental and institutional culture more welcoming and equitable to a diversity of students; and contribute to an evolving curriculum for future students. It also aims to provide faculty opportunities to: be recognized and compensated for the time they spend on mentoring and advising; develop insights into what students bring and can contribute not only to this curriculum but also to a cultural shift in the department and at the College overall; and support students and other faculty in partnering to foster a sense of belonging and transform institutional culture.

The participating faculty are piloting the course in the 2020–2021 academic year, co-developing it with a group of students and working in collaboration with other offices and individuals on campus to forge links and share resources. The course design includes an action research component, and the faculty/staff facilitators and the student participants will be co-researchers of this pilot, thereby enacting another form of student-faculty/staff partnership that complements the “pedagogical consultancy” model (Healey et al., 2016) we already have with SaLT.

6 Conclusion

A growing body of research documents the potential of partnership to deepen engagement and enhance learning and teaching (Cook-Sather et al., 2014; Curran & Millard, 2016; Ferrell & Peach, 2018; Healey et al., 2014; Marquis et al., 2018; Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017), foster more equitable and inclusive practices (Cook-Sather & Des-Ogugua, 2018; de Bie et al., 2019), and transform institutions (Cook-Sather et al., 2019a; Perez-Putnam, 2016). The different forms of pedagogical partnership we describe here contribute to greater equity and inclusion in several ways. The position of “student consultant” itself complicates the institutional roles of student, instructor, and educational developer; the role of student consultant and the SaLT program position students to mobilize their own cultural identities; and the partnership work contributes to the transformation of the institution into one that recognizes, values, and builds on the diverse knowledges of its members (Cook-Sather et al., 2019a).

As our examples illustrate, engaging in this work has the potential to link micro-level partnership efforts with meso- and macro-levels of transformation. As one student partner reflected, “working with [a] specific professor in the moment but also towards a far-away future Haverford in which all professors have had the same opportunity to think about their pedagogy within the space of the SaLT program,” student consultants both benefit from and contribute to this equity work (Perez-Putnam, 2016), and they support faculty engagement in equity efforts.

The development of a college-wide, co-created course focused not only on navigating but also on transforming the institution suggests that work done through individual SaLT partnerships and student-faculty collaborations such as those White, as a STEM faculty member, embraced at the micro level with Aramburu and Samuels and at the meso level with Wynkoop have the potential to inform wider institutional change. Another student partner who worked with several STEM faculty partners offered an insight that might also be read as an injunction: “If we all engaged in partnerships through which we reflect and discuss how teaching and learning experiences can include and value everyone, our campuses would become places of belonging” (Colón García, 2017).

As Takayama et al. (2017) argued in their pre-conference workshop at the ASCN Transforming Institutions Conference, and as the brief descriptions we offer here of change leaders working at Haverford College at the micro (individual teacher and classroom), meso (department and center), and macro (institution-wide) levels suggest, such concerted, cross-level efforts premised on partnership between faculty and students hold great promise for transformation and systemic change.

7 About the Authors

Alison Cook-Sather is Mary Katharine Woodworth Professor of Education at Bryn Mawr College and director of the Teaching and Learning Institute at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges.

Helen K. White is an Associate Professor of Chemistry and Environmental Studies at Haverford College.

Tomas Aramburu is a graduate of Haverford College and while there was the co-founder of the student organization Underrepresented Minorities in STEM.

Camille Samuels is an undergraduate student at Haverford College.

Paul Wynkoop is graduate of Haverford College and was a Student Consultant in/for the Teaching and Learning Institute (TLI) at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges.

8 References

Callahan, K. M., Williams, K., & Reese, S. (this volume). “Student leaders as agents of change.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 16). Pressbooks.

Charkoudian, L., Bitners, A. C., Bloch, N. B., & Nawal, S. (2015). Dynamic discussions and informed improvements: Student-led revision of first-semester organic chemistry. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education (15). https://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss15/5/

Chasteen, S., Code, W., & Sherman, S. B. (this volume). “Practical advice for partnering with and coaching faculty as an embedded educational expert.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 21). Pressbooks.

Colón García, A. (2017). Building a sense of belonging through pedagogical partnership. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education (22). http://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss22/2

Cook-Sather, A. (2016). Undergraduate students as partners in new faculty orientation and academic development. International Journal of Academic Development 21(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1156543

Cook-Sather, A. (2018). Developing “Students as Learners and Teachers”: Lessons from ten years of pedagogical partnership that strives to foster inclusive and responsive practice. Journal of Educational Innovation, Partnership and Change, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.21100/jeipc.v4i1.746

Cook-Sather, A. (2019). Increasing inclusivity through pedagogical partnerships between students and faculty. Diversity & Democracy, 22(1). https://www.aacu.org/diversitydemocracy/2019/winter/cook-sather

Cook-Sather, A., & Agu, P. (2013). Students of color and faculty members working together toward culturally sustaining pedagogy. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 32(1), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2013.tb00710.x

Cook-Sather, A., Bahti, M., & Ntem, A. (2019b). Pedagogical partnerships: A how-to guide for faculty, students, and academic developers in higher education. Elon University Center for Engaged Learning Open Access Series. https://doi.org/10.36284/celelon.oa1

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in teaching and learning: A guide for faculty. Jossey-Bass.

Cook-Sather, A., & Des-Ogugua, C. (2018). Lessons we still need to learn on creating more inclusive and responsive classrooms: Recommendations from one student-faculty partnership program. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(6), 594–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1441912

Cook-Sather, A., Krishna Prasad, S., Marquis, E., & Ntem, A. (2019a). Mobilizing a culture shift on campus: Underrepresented students as educational developers. New Directions for Teaching and Learning (159), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20345

Curran, R., & Millard, L. (2016). A partnership approach to developing student capacity to engage and staff capacity to be engaging: Opportunities for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1120212

de Bie, A., Marquis, E., Cook-Sather, A., & Luqueño, L. (2019). Valuing knowledge(s) and cultivating confidence: Contributions of student-faculty pedagogical partnerships to epistemic justice. In P. Blessinger, J. Hoffman, & M. Makhanya (Eds.), Strategies for fostering inclusive classrooms in higher education: International perspectives on equity and inclusion (pp. 35–48). Emerald Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2055-364120190000016004

Delgado Bernal, D. (2002). Critical race theory, Latino critical theory, and critical raced-gendered epistemologies: Recognizing students of color as holders and creators of knowledge. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800107

Ferrare. J. J., & Lee, Y. G. (2014). Should we still be talking about leaving? A comparative examination of social inequality in undergraduates’ major switching patterns [WCER Working Paper No. 2014-5]. http://www.wcer.wisc.edu/publications/workingPapers/papers.php

Ferrell, A., & Peach, A. (2018). Student-faculty partnerships in library instruction. Kentucky Libraries, 82(3), 15–18.

Greenhoot, A. F., Aslan, C., Chasteen, S., Code, W., & Sherman, S. B. (this volume). “Variations on embedded expert models: Implementing change initiatives that support departments from within.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 22). Pressbooks.

Halasek, K., Heckler, A., & Rhodes-DiSalvo, M. (this volume). “Transforming the teaching of thousands: Promoting evidence-based practices at scale.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 20). Pressbooks.

Healey, M., Flint, A., & Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement through partnership: students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. Higher Education Academy.

Healey, M., Flint, A., & Harrington, K. (2016). Students as partners: Reflections on a conceptual model. Teaching and Learning Inquiry 4(2). https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.4.2.3

Klein, C., Lester, J., & Nelson, J. (this volume). “Leveraging organizational structure and culture to catalyze pedagogical change in higher education.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 19). Pressbooks.

Marquis, E., Guitman, R., Black, C., Healey, M., Matthews, K. E., & Dvorakova, L. S. (2018a). Growing partnership communities: What experiences of an international institute suggest about developing student-staff partnership in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2018.1424012

Mathrani, S. (2018). Building relationships, navigating discomfort and uncertainty, and translating my voice in new contexts. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education (23). https://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss23/6

Mathrani, S., & Cook-Sather, A. (2020). “Discerning growth: Tracing rhizomatic development through pedagogical partnerships.” In L. Mercer-Mapstone & S. Abbot (Eds.), The power of partnership: Students, staff, and faculty revolutionizing higher education (pp. 159–170). Elon University Center for Engaged Learning Open Access Series. https://doi.org/10.36284/celelon.oa2

Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S. L., Matthews, K. E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., Knorr, K., Marquis, E., Shammas, R., & Swaim, K. (2017). A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119

Narayanan, D., & Abbot, S. (2020). “Increasing the participation of underrepresented minorities in STEM classes through student-instructor partnerships.” In L. Mercer-Mapstone & S. Abbot (Eds.), The power of partnership: Students, staff, and faculty revolutionizing higher education (pp. 181–195). Elon University Center for Engaged Learning Open Access Series. https://doi.org/10.36284/celelon.oa2

Perez, K. (2016). Striving toward a space for equity and inclusion in physics classrooms. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education (18). http://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss18/3

Perez-Putnam, M. (2016). Belonging and brave space as hope for personal and institutional inclusion. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education (18). http://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss18/2

Salomone, S., Dillon, H., Prestholdt, T., Peterson, V., James, C., & Anctil, E. (this volume). “Making teachers matter more: REFLECT at the University of Portland.” In K. White, A. Beach, N. Finkelstein, C. Henderson, S. Simkins, L. Slakey, M. Stains, G. Weaver, & L. Whitehead (Eds.), Transforming Institutions: Accelerating Systemic Change in Higher Education (ch. 17). Pressbooks.

Sible, J., Wojdak, J., Gough, L., Moss, P., Mouchrek, N. M. (2019, April 4). Sustaining inclusive excellence [Paper presentation]. ASCN Transforming Institutions Conference, Pittsburgh, PA.

Takayama, K., Kaplan, M., & Cook-Sather, A. (2017). Advancing diversity and inclusion through strategic multi-level leadership. Liberal Education, 103(3–4). http://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/2017/summer-fall/takayama_kaplan_cook-sather

White, H., & Wynkoop, P. (2019). Pink bagels and persistence. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education (28). https://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss28/6

Wynkoop, P. (2018). My transformation as a partner and a learner. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education (23). https://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss23/4