About Falcons

11 Falconry

History of Falconry

This section is provided through the courtesy of the International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey.[1]

At the Abu Dhabi Symposium on “Falconry: a World Heritage” in September 2005, experts on many aspects of falconry met and gave presentations on their various specialities. Falconry from all regions of the world was represented, and many exciting facts came up that were previously unknown to those of us restricted to learning from our own compatriots and from books written in our own language. Here is a short summary from a layman’s point of view. Apologies to those countries whose names and histories do not appear; the number of experts that were able to attend the symposium was sadly limited.

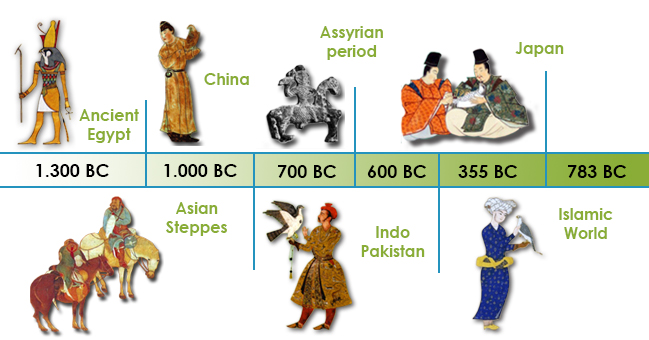

A significant problem with recorded history is that history can only be recorded where records exist. We are certain the origins of falconry go back much further than the origins of writing because the earliest written records found describe a highly organized and technical falconry that must have taken many hundreds, if not thousands of years to evolve to that level of sophistication. Many experts present at the Symposium are engaged in full-time research into this elusive subject.

History has its uses.

Falconry is not a museum piece; it is alive. We can enjoy and promote all the best of modern falconry and support its traditional forms as well. We must protect and promote these vulnerable, minority aspects and practices of falconry as precious embodiments of world cultural history. The project to have aspects of falconry recognised by UNESCO encourages research into the social history of falconry, enriches the historical consciousness of falconers and promotes and safeguards falconry for future generations.

Falconry in Mongolia

Falconry was practiced in Mongolia at a very remote period and was already in high favor some 1,000 years BC; that’s 3,000 years ago. It achieved a very high level of refinement on the military campaigns of the Great Khans, who practiced falconry for food and for sport between battles. One such military expedition reached almost to the gates of Vienna. By the time of Marco Polo, there were over 60 officials managing over 5,000 trappers and more than 10,000 falconers and falconry workers.

Falconry in Korea and China

Falconry was combined with legal and military affairs, diplomacy, and land colonization, and moved accordingly, reaching Korea in 220 BC and Japan much later.

In China, falconry once occupied a very significant role—there are many historic remains in literature, poems, painting, and porcelain describing it in the culture of the imperial family, the nobility and the social life of the ordinary people. Chinese falconry had an inseparable relationship with politics and power and written records go back prior to 700 B.C. These depict a very mature and technical falconry, exactly parallel with techniques used today. The imperial family of the time (Chu Kingdom) were already using falcons, eagles, and shortwings in exactly the same way we do. This would put the birth of falconry in the region (if indeed this was where falconry was born) at over 3,000 years ago.

Falconry was strong in China right into the early 1900s. It enjoyed imperial patronage and was popular among the aristocracy and even common people all through the centuries, largely due to the medieval society China endured all this time. With the decline and fall of the imperial family in 1912, falconry at the aristocratic level became feeble and died. At the same time, the falconry of the common people declined through conflict between ethnic groups, invasion by eight different foreign countries, and ultimately World and Civil Wars. It survived in ethnic minority groups—the Hui, Weir, Naxi, etc., until in the late 20th century, falconry in China revived, and it has been estimated that there are almost as many falconers inside China than outside it.

Falconry in Japan

Japan’s isolation by the sea meant that the natural advance of falconry did not come till quite late; the first written records are from 355 A.D. (Nihon Shoki) from Paekche (old kingdom in Korea), documented hawks exported from Korea to Japan. There is archaeological evidence then from the 6th century onwards. In ancient times, Japanese hawking was done by falconers on horseback and armed with bows on their back. This gave a deliberate martial effect to a hawking party, designed to intimidate and overawe lesser mortals. The scene of a hawking departure deeply impressed spectators, so hawking was used very effectively to symbolize and publicly demonstrate military power and dominance over the land. Hence the central rulers always tried to monopolize or even ban hawking through laws and Buddhist ideology, while the emerging local lords kept hawking in practice either through connections with those in influential positions or through finding religious excuses in Shintoism. This importance of public demonstration in Japanese falconry created a tradition of beautiful costumes and elaborate equipment the aesthetics of which have survived to the present day.

Imperial Falconers existed under the Imperial Household Ministry until the Second World War, after which it became open to distribution to the public by a system of apprenticeships to retired imperial falconers leading to the “Schools of Falconry”, the Yedo school, the Yoshida School, etc., the ideals of which exist to the present. There was also a tradition of subsistence hunting with Mountain Hawkeagles from the early 19th century. Unfortunately, this bore the brunt of opposition by birdwatcher fanatics and it has almost disappeared.

Falconry in Iran and Persia

Despite a belief that falconry originated in the Mongolian steppes, Iran/Persia is sometimes also cited as the cradle of falconry. A theory put forward at the Symposium suggested a possible “parallel evolution”—with the first hunting birds of prey trained at around the same time in both the Mongolian steppes and in Iran. In documented Iranian history, the one who used birds of prey for the first time was Tahmooreth, a king of the Pishdadid dynasty, 2,000 years before Zoroaster, who himself lived around 6000 B.C.

This could mean hunting with falcons has a background of 8,000 to 10,000 years. This was one of the most interesting hypotheses at the Symposium and was presented with several proofs, dates of dynasties, approx lengths of generations, and reigns.

Falconry in India

In India, falconry appears to have been known from at least 600 years B.C. Falconry became especially popular with the nobility and the Mughals were keen falconers. Surprisingly, the humble sparrowhawk was the favorite of the mighty Emperor Akbar. In the Indus Valley, falconry was considered a life-sustaining instrument for the desert dwellers, while those from the green belts considered it as a noble art and used the falcons as symbol of high birth and luxury. Organized hunting parties would go out for game. Richard Burton, the famous 19th Century historian and translator, wrote extensively about falconry in the Indus Valley, citing the interesting practices of its communities in his book “Valley of the Indus.”

In the Rajput States—in Jaipur, Bhavnagar, etc., the royal families continued to cherish the sport of hawking till the 1940s, but then partition and subsequent political problems all but did for falconry in India. Nowadays, while there are many people who have paper knowledge of the birds, there are very few with practical knowledge left.

Arab Falconry

Falconry appeared with the emergence of civilizations and was already popular in the Middle East and Arabian Gulf region several millennia B.C.

In the Al Rafidein region (Iraq), it was widely practiced 3500 years B.C; in 2000 B.C., the Gilgamesh Epic clearly referred to hunting by birds of prey in Iraq.

The Babylonians created a Divan for falcons and made game reserves for quarry species. Al Harith bin Mu’awiya, an early King of the present region that includes Saudi Arabia, was one of the first who trained and hunted falcons. The Omayyad caliphs and princes, Mu’awiya bin Abi Sufyan and Hisham bin Abdul Malek, practiced falconry, and falconry had a good position in the Abbasid period. The caliph Haroun Al Rasheed was fond of the sport and exchanged falcon-gifts with the other kings.

The Arab poets composed a lot of poems lauding the falcon and all Arab classes—Kings, Sheikhs and cavalry—practiced falconry and bequeathed it to the next generations. The Arabian Gulf region became famous for its falconers and falconry traditions.

Through Arab influence, it spread out through the Islamic World, eastwards into the great Islamic Empires of Central Asia and westwards across North Africa to the Magreb, giving us the distinctive styles of falconry of the Bedouin, of the Kingdom of Morocco and the Magreb, and of Tunisia (passage sparrowhawks at quail—note similarities with the falconry of eastern Turkey and Transcausasia).

The Holy Koran itself includes a falconry-related verse that permits falconry as a hunting method. Falconry is considered a symbol of this region’s civilization more than any other region in the world; 50% of the world’s falconers exist in the Middle East, which includes the Arab region.

In the philosophy of the region, hunting trips teach patience, endurance, and self-reliance, and bravery can be learned from falcons.

Falconry in Russia

Falconry in Russia has an ancient history, its roots found probably in the 8th and 9th centuries. It came to the Eastern Slavic tribes from their southern neighbours and from the Huns and Khazars, the Turkic speaking nomadic nation who created in the 5th century a country whose boundaries stretched over the modern Dagestan, Cis-Azov Sea area, the Crimea, the Don River region, and the Lower Volga River area. At the end of the 9th century, the ancient Russian knight Oleg built the falcon yard in Kiev. Vladimir, son of Yaroslav Mudryi, who ruled between 1019-1054, issued the first legislative acts regulating falconry. Historical chronicle returns many times to the mention of falconry as an important feature of the everyday life of Russian princes. Falconry was loved by Prince Igor, famous for his unsuccessful military trip to Polovets in 1185. Even when in captivity, this prince did not change his habits and continued to fly hawks.

An interesting legend exists about Saint Trifon, whose day is celebrated by orthodox Christians on 14th February: the boyar (nobleman) Patrikiev had the bad luck to lose a falcon belonging to Tsar Ivan the Terrible. Fearing the worst, he prayed to a local saint, Trifon (or Triphon), to show him where it was. Sure enough the saint appeared in a dream and showed him where to look. In return, the boyar built and dedicated a church. Religious icons of St. Trifon show him in a falconer’s pose with a falcon on his fist.

During the middle ages, falconry flourished in Russia, especially in the Moscow Principality. One of the Moscow districts is even now known as “Sokolniki”, which translates as “Falconers” or “Site of Falconers”. Falconry had its heyday during the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov (1626-1676), father of Peter the Great, but, as elsewhere, it had practically died out among the elite of Russian society by the end of 19th-beginning of 20th century. After October 1917, falconry was not officially prohibited, but was not supported by the government, and that, in reality, meant one and the same thing. However, in two regions where falconers were simple common people, it continued to exist: in Transcaucasia and in the republics of the Middle Asia, where falconry was one of several hunting methods for acquiring food or furs.

Falconry in Turkey

Excavations at the ancient Hittite city of Alacahöyük, which was inhabited in 4,000 B.C., show various relief sculptures dating back to 1600-1200 B.C., such as a double headed Eagle, a symbol that is very ancient and also present at the Assyrian colony at Kanesch (Kültepe).

Discoveries at the Karatepe (meaning ”black hill” in Turkish) complex date back to 1600-1400 BC and were excavated from 1947 to 1957. The excavations revealed the ruins of the walled city of king Azatiwataš, where two city gates have many reliefs covering the lower walls of the gate complex. An image of a god riding a bull, with what looks like a Bird of Prey in one hand and a Hare in another is present.

This symbolic and actual relationship with Birds of Prey extended into the Seljuk period of Turkey and beyond, with the crowning of Tuğrul (which means Falcon) Beg at Mosul in 1058 as “King of the East and the West”. The double-headed Eagle became the standard of the Seljuk Turks and has been much used afterwards right up until today including Government institutions.

During the Ottoman Empire, falconry in Turkey reached its pinnacle at what is seen as the Golden Era, when it was practiced by the elite of the ruling class. Falconry during this period had been responsible for ransoms, bribes, as well as the death of intended heirs to the throne.

This love and passion in which the Ottoman court held Falconers and Falconry was recorded by the eyewitness statements of both John Sanderson (1594) and Thomas Dallam (1599). The Turks were responsible for much intercultural exchange with the Europeans, including falconry during the Crusades.

With the decline of the Ottoman Empire came the decline of falconry in Turkey, with this decline still continuing today. It is estimated that there are approximately 4,000 Falconers currently in modern day Turkey (2012), mainly around the Black Sea region and practiced also around Istanbul. Falconers are only allowed to use sparrowhawks (Atmaca), which they trap under license from the Turkish Government to hunt migrating Quail. This tradition is centuries old, which has been passed down orally through generations.

Falconry in Georgia

Falconry is known in Georgia since the 5th century and is most remarkable for its tradition of flying passage sparrowhawks at quail. This was clearly described in literature of the early 19th century and similar living traditions exist today in Tunisia and Turkey.

For many centuries, ordinary people in Western Georgia have hunted with sparrowhawks, while the more elite of society of Eastern Georgia flew goshawks and falcons. Georgia was the first of the former Soviet states to formally legalize falconry in 1967. In the town of Poti, there is a monument devoted to bazieri (sparrowhawkers).

There are over 500 registered bazieri at the present time.

Falconry in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is a country the size of Europe—mountain and steppe, barely touched by modern civilization and whose inhabitants are mostly farmers and part-time farmers. Its falconers continue the Central Asian tradition of flying golden eagles at hare for food and at fox and wolf for furs and flock. Until modern times, this was a subsistence necessity for the peoples of Kazakhstan, as well as in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan and Mongolia and the ethnic minorities in Western China.

Falconry tradition in Turkmenistan differs greatly from the neighboring traditions of eagles in Kazakhstan and the other central Asian republics to the north and east. It is much more like the traditional falconry of Iran and Afghanistan using sakers and tazy (the Turkmen version of the saluki) at the desert hare. Falconers traditionally spend five months of the year in the desert staying with their hawks, their tazy, and their falconry mentors. The Oguz Khan tribes, forefathers of the Turkmen people who lived 5,000 years ago, had falconry symbols on their ancestral emblems, carpets, pottery, and other archaeological finds. In literature, falconry appears in many Turkmen classics of the 15th-17th centuries; authors such as Sayilly, Makhtumkuli, Seyidi, and Mollanepes were also falconers.

There are more than 60 proverbs and sayings in Turkmen folklore that cite falcons and falconry. Falconry is seen as a sign of equality. You find the falcon carried by the countryman as well as the city-dweller, by workers as well as academic or cultural workers; it is seen as instilling ideals of nature protection.

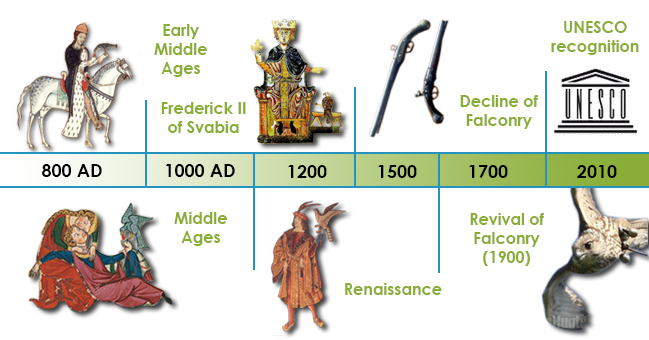

Falconry in Europe

The earliest evidence of falconry in Europe is usually considered to be from the 5th century A.D., written quotations from Paulinus of Pella and Sidonius Apollinaris in France and the famous mosaics in the Falconer’s Villa in Argos (Greece). For over a thousand years, falconry was extremely popular in Europe and carried enormous cultural and social capital. A marker of high social status, falconry was considered an essential part of a gentleman’s education, for it was thought to prevent sickness and damnation and demanded the cultivation of personal qualities such as patience, endurance, and skill.

Using the term ‘European’ falconry is in one sense misleading, because falconry techniques and technologies have been traded across European and other countries for centuries. For example, in the 13th century, Arab falconry techniques were imported into Europe through Spain and through the court of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in Sicily. He employed Arab, English, Spanish, German, and Italian falconers, and translated important Arab falconry works. His masterwork “De arte venandi cum avibus” distills the falconry knowledge of many cultures.

Falconry was a means of cultural communication, because its symbolic system was shared between most cultures of the known world and falcons made ideal diplomatic gifts. Its geographical reach was extraordinary. 17th century falcon-traders brought falcons to the French Court from Flanders, Germany, Russia, Switzerland, Norway, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Spain, Turkey, Alexandria, the Barbary States, and India. Falconry wasn’t merely an amusement; it was a fierce articulation of social and political power; a deadly serious pastime, considered among the finest of all earthly pursuits—and big business.

By the end of the 17th century, the use of falcons as diplomatic gifts gradually faded, and falconry’s connection with nobility won it no favors after the French Revolution. It faded away in favor of the new sport of shooting. By the 19th century, only a very few individuals still practiced the sport in Europe. Now, falconry clubs became necessary not simply to maintain both the social traditions of falconry, but the knowledge of falconry itself.

Somehow, falconry’s living tradition survived with just sufficient falconers to pass on their treasured knowledge. Falconry had a renaissance in most European countries in the 1920s and 1930s, and its popularity increased further in the 1950s and 1960s.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, much of falconry’s intangible heritage was safeguarded by what UNESCO calls living treasures—proficient falconers who could teach apprentices not only the practical methods of falconry, but also its intangible dimensions. They communicated the ethical codes of falconry sportsmanship and could instill in their pupils an awareness of the emotional bonds falconers have with their falcons, quarry, and hawking land.

Falconry in Spain and Portugal

Spain and Portugal. Recent exciting discoveries of images from the 3rd century B.C. in Eastern Spain, that show falconry scenes, are currently under scrutiny by academics. Until these were found, scholars believed falconry entered Spain in the 5th century A.D., coming from North Africa with the Moorish Kings and along the northern Mediterranean coast from Eastern Europe with the Goths at approximately the same time. Much of the history of pre-16th century Iberian falconry is intertwined with Arab falconry of the time and written references abound in the Arabic language, for example, in the 10th century.

Calendar of Cordoba and from Abd al-Yalil ibn Wahbaun in the 11th century. There are Islamic falconry images like the Leyre Chest. (1004-1005 A.D.), now in the Pamplona Museum, and the Al-Mugira jar. (968 A.D.), now in the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Whereas in other parts of Western Europe, many falconry terms have their origins in medieval French, in Spain and Portugal, there are many terms derived from Arabic.

Old Spanish and Portuguese books on falconry are numerous and stretch from the very early “Libro de las animalias que cazan” in Spanish, 1250, through Viscount Rocabertí’s “Libre de cetreria” in Catalan c.1390 to Diogo Fernandes Ferreira’s “Arte de caça de altaneria” 1616 in Portuguese and now in an English translation.

After a gap of two centuries, falconry in Spain was recovered from scratch by Dr. Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente in the 1950s. Not having any practicing falconer around in Spain, his sources were Spanish medieval falconry literature and foreign falconers like the late Abel Boyer of France. In 1964, de la Fuente wrote his outstanding “El Arte de Cetrería” a masterpiece and a book of great influence not only in the Spanish, but for serious falconers everywhere. Félix, known as “the friend of animals”, was one of the most popular celebrities in Spain thanks to his TV series on wildlife.

In the 1980s, falconry started to flourish in Spain and Portugal, and currently, Spain is numbered in the top five falconry nations.

Falconry in Netherlands

For centuries, the Netherlands was the center of European falconry. Currently, it has some very draconian laws regulating falconers; nevertheless falconry survives and thrives at a high level. The number of falconers allowed is 200 over the whole of the Netherlands and they are permitted to fly only goshawks and peregrines at quarry.

Five clubs exist, the largest two being the Nederlands Valkeniersverbond, Adriaan Mollen and the Valkerij Equipage Jacoba van Beieran. The heyday of falconry in the Netherlands came in the first half of the 19th century, when it was a hub for falcon trading and trapping.

With royal patronage from the House of Orange and participation by gentlemen falconers from Holland, England, France, and elsewhere in Europe, the Loo Club was founded in 1839 and enjoyed a standard of “high flight” falconry at passage herons not seen since the 1600s.

The Netherlands has two falconry-related collections: the world famous falconry museum in Valkenswaard, the 18th and 19th century center for hawk trapping, which supplied hawks and professional falconers to the whole of Europe. There is also a globally important collection of over two hundred falconry-related books and other items in the National Library of the Netherlands, centered on a bequest in the late 1940s by Professor A. E. H. Swaen.

There is also a Falconry Historical Foundation concerned with the history of the sport.

Falconry in Belgium

Belgium, so near to Valkenswaard and the main passage routes for migrating birds of prey, also became renowned for commerce in hawks and its falconers in the early-modern period. Arendonkís falconers were renowned from the 12th century and the region of the Kempen was the homeland of Europe’s finest professional falconers. Some families provided falconers for about 5 centuries. Nearly all of the well-spoken, multilingual, and cultured falconers who worked for Europe’s 15th to 18th century ruling families were Flemish or Dutch.

The city of Turnhout even had a special court for falconers. The last falconmaster of the King of France in the 1880s was a falconer from Arendonk. By the 1900s, falconry had almost died out in Belgium, but found a new start in 1912 with Viscount Le Hardy de Beaulieu, who entertained an “Équipage” for crows and magpies led by a professional falconer till 1927. The true revival came with Charles Kruyfhooft in the late 1930s. Charles was probably the last European falconer to trap passage peregrine falcons following the famous method used in Valkenswaard with a very sophisticated trapping hut. He flew crows and rooks each winter for about sixty years till his death in 1995.

By the end of the second World War, there remained only three active falconers in Belgium, but by 1966, Belgian falconry had grown sufficiently for its falconers to form their own national organization, the Club Marie de Bourgogne, named for the queen who died while hawking in 1482. Political lobbying by falconers persuaded the government to grant a limited number of licenses to keep peregrines, goshawks, or sparrowhawks in order to keep the cultural heritage of falconry alive.

There are many private collections of falconry art, tapestries, books, and literature in Belgium, and two small falconry collections at the chateau of Lavaux Sainte Anne and at Taxandria Museum in Turnhout. The holy falconer’s patron, “Saint Bavo”, was born and lived in Belgium; he is buried in Gent.

Falconry in Ireland

In Ireland, falconry was already familiar by late Celtic times (7th century on), but written references are more to the monetary value of hawks than to descriptions of the sport, pointing at an export trade rather than a native use.

Falconry was responsible for the earliest legislation protecting raptors, there are references in the Brehon Laws Ireland supplied the nobility of Western Europe with peregrines and goshawks until the end of the 19th century, and the aristocracy of several nations brought their hawks there to hunt.

An Irish Hawking Club was formed in 1870 at a meeting chaired by Lord Talbot de Malahide. Maharajah Prince Duleep Singh, a familiar figure in falconry circles across two continents, pledged £50 to its founding. There has been a strong tradition of flying the sparrowhawk in Ireland, and Irish falconers have enjoyed international renown.

Falconry in France

In France, falconry reached its heights of complexity, scale and magnificence in the 17th century under Louis XIII. His falconry consisted of 300 birds, subdivided into six specialized équipages: for the flight at the heron, the flight at the kite and the crow, the flight at the river, the flight at the partridge, and so on. Numerous paintings, tapestries, and works of literature survive from this period.

It slipped off the law after the revolution when a scribe neglected to include falconry in the list of acceptable hunting techniques in 1844 hunting legislation and although it continued under the Empire there was no legal provision for it. A revival came after the last war.

In 1945, the Association Nationale des Fauconniers et Autoursiers Français (ANFA) was formed. It aimed to legalize, revive, and popularize falconry and protect raptors. It was instrumental in obtaining full legal protection for French birds of prey. Today, ANFA has around 300 members, who fly a wide variety of hawks and falcons.

France has a special significance for the cultural heritage of falconry. In 1999, it submitted the Pierre-Amédée Pichot collection at the Museum of Arles for inclusion in the UNESCO World Register; it is undoubtedly among the most significant falconry-related archives in the world. The International Musée de la Venerie in Gien also has a falconry collection, including significant fine art and tapestries.

Falconry in Italy

Falconry reached Italy from three different routes: from Arab falconers through the Norman Court in Sicily; from the north through German influence, and through Venetian contacts with falconers in Asia and the Orient. A wealth of literature, art, and records exists on falconry in both medieval and early modern times.

Among the most famous—or infamous—falconers of the period include Lorenzo de Medici, Lucrezia Borgia, Francesco Foscari, the Doge of Venice, and Cardinal Orsini. And of course, the most famous falconer, claimed by both Italy and Germany, Federico II, Holy Roman Emperor (1154-1250).

Starting from 1700, we see a progressive decline of falconry in Italy. By the 1900s, falconry had almost died out. A new interest revived in the early 20th century and the publication of falconry books by Chiorino and Filastori in 1906 and 1908 helped reawaken an interest in the sport. The “Coppaloni” style or “Italian” style, was a training and flying style as well as a “philosophical” new way to interpret the magic of falconry.

Dr. Coppaloni was a pharmacist, physician, eclectic sculptor, dog lover, and judge of racing dogs, breeder of pointers, and he never left a paper on his work or his hunting techniques. Coppaloni’s advice was to look primarily for flight style purity; this should be always pursued even at the cost of limiting the number of kills. In the 1960s, he demonstrated his hunting style during a meeting in Spain, where Felix Rodriguez de la Fuente was flying cul levé at the red-legged partridge with falcons; his performance was received with enthusiasm. Fulco Tosti di Valminuto, the first disciple of Coppaloni, spent two years on Torrejon flying field near Madrid exhibiting to Spanish falconers the Coppaloni’s technique.

In 1967, Coppaloni organized a meeting in Settevene, near Rome. Among the people attending the meeting there was the great Renz Waller, President of German Falconers, Jack Mavrogordato, Mrs. Woodford, Charles De Ganay, and others. At the end, after many hunting flights, there was the unforgettable flight of Frikki Pratesi peregrine, named Fulvia. She performed all her pitch over the falconer, but remained completely out of sight, till the descent to stoop her gray partridge in an astonishing way.

Today, Italian falconers fly longwings at pheasant, partridge, quail, crows, and magpies, and goshawks at rabbits and hares. Classical game hawking is exceptionally hard to practice, due to competition for land with strong shooting interests.

Italian museums with important falconry collections include the Castel del Monte and Castello di Melfi, both in the Puglia region, the Fortezza del Girifalco in Arezzo, Museum of Bargello in Florence and the Vatican library in Rome. Castello di Melfi is of particular importance; it was Frederick von Hohenstaufen’s castle and continues to host an annual falconry field meeting.

There are many local falconry clubs and two national ones. As in other countries, falconers have pioneered conservation reintroduction programs for peregrines and eagle owls.

Falconry in Germany

The period from 500 to 1600 saw the zenith of falconry in Germany. Particularly notable past German falconers include, of course, Emperor Frederich II, and the fanatical 18th-century falconer, Margrave Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von Brandenburg-Ansbach. By 1890, however, only a single hawking establishment remained in Germany, that of Baron C. von Biederman. A small number of falconers practiced the sport in near-isolation until a falconry revival began in 1923, and the establishment of the Deutscher Falkenorden, and today the DFO is a thriving organization with over 1,000 members and is the oldest falconry club in the world. The Orden Deutscher Falkoniere has around 250 members, and the Verband Deutscher Falkner, a former GDR club, has approximately 100 members. German falconry remains highly traditional. Dedicated hunting-horn music is played to greet falconers when they arrive at falconry meets, when they depart to the field to hunt, and to honor the quarry as it is laid out by torch or firelight at the end of the day. After the meet, falconers attend a celebratory feast, hawk on fist.

Falconry in Denmark

In Denmark, 6th century documents record that Rolf Krake and his men on a visit to King Adils in Uppsala each carried a falcon on his shoulder. Remains of hawks are found in the graves of important Vikings.

Later on, in 985, there is a record of 100 marks and 60 hunting falcons paid in annual levy by Hakon Jarl to Harald Blåtand as rental for a part of Norway. King Knud the Holy (1040-86) was a competent falconer, as were several kings up to Frederik the Second (1559-88) who established a royal falconry.

In 1662 Crown Prince Christian, later King Christian V, spent some time at the court of Louis XIV and on his return to Denmark founded a small falconry. A royal mews existed till 1810, and the last royal hunt with falcons was in 1803 to mark a visit by the Duke of Gloucester.

Falconry in Iceland and Norway

Both Iceland (Danish territory) and Norway were well known for gifts of goshawks and gyrfalcons to foreign sovereigns. In the 18th century, at least five shipments of falcons were sent to the Emperor of Morocco. No less than fifty different courts received these presents. In 1764, fifty falcons went to the French King, 30 to the German Emperor, 60 to the King of Portugal, 20 to the Landgrave of Hesse and 2 to the French Ambassador. Gifts of falcons to France continued until a few months before the execution of Louis XVI when the falconry in Versailles was abolished (1793). The last time the Emperor of Morocco received falcons was in 1798 and the Portuguese court in 1806.

In modern times, a few people kept falconry alive in Denmark after the cessation of royal patronage, but so few that a Hunting Act in 1967 effectively prohibited it. The Danish Hawking Club quickly established good relations with politicians and civil servants and is working hard to reverse this ban.

Falconry in Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe form a distinct region of influence—for much of recorded history forming or being part of a single empire, whether Czech-Moravian, Austro-Hungarian, Germanic, or even Soviet.

Many sovereigns immortalized their favorite falcons by showing them on coins, the Silver Dinar of Béla the IV, King of the House of Árpád (present day Hungary). On one side of the coin, you can see a hawk catching a rabbit.

There is also a falconer on horseback on a coin from 12th century Czech-Moravia and on the current Hungarian 50 Florin coin there is a falcon. A widespread legend in Eastern Europe is the “Turul” cycle, which cannot even be understood without a significant knowledge of falconry. The huge amount of medieval paintings that still exist in the region indicates the great impact falconry had on the development of fine art.

We know that birds of prey used for falconry were very important goods of exchange of medieval trade, and Eastern European sovereigns regularly imported gyrfalcons from Scandinavia, Iceland, or Northern Siberia and other falcons from Southern Europe and Northern Africa. Trading with falcons was a significant part of medieval commerce and involved entire families.

Whole villages specialized in catching, training, and trading of falcons and falconry-related handicraft, hand manufacturing of hoods, gloves, satchels, and leg straps, was practiced to a high artistic level. Hungary has been famous from medieval times to the present day for highly artistically decorated equipment, and falconers still make these items in an almost unchanged form.

From 16th century Transylvania, during the Turkish occupation, sakers were regularly delivered to the Turkish Sultan. This tax, paid annually in return for peace, was called “Falco nagium”. Sales contracts have even been found where the parties mentioned exact cliffs where the falcons nested, stipulating to the buyer he would have to give the seller young birds from the nest each year for a set time.

The present-day Czech Falconry Club of the Czech-Moravian Hunting Union is one of the largest and most influential of the central European clubs and has researched the history of falconry in the region.

The earliest artifact is a 5th century clip in the shape of a falcon, now in the National Museum in Prague. The Fulda Annals report Prince Svatopluk rejoicing in his hunting falcons around 870 A.D. and later (13th century) the city of Sokolov began near the site of the Falcon’s Manor of Loket Castle. NB the Czech word “sokol” = falcon. Another falconry at Poděbrady continued until the 17th century with patronage of the Emperor Ferdinand 1st and his son Ferdinand the Vice-Regent of Prague.

Falconry held on with one or two dedicated individuals until 1967, when 71 falconers and guests founded the present club.

In Poland, the earliest written records from the 11th century mention falconry as being widely practiced all over the country. There are physical artifacts of falconry from that time, like a 13th century horn knife handgrip in the shape of a lady falconer feeding a falcon on her fist. Permission to hunt was a privilege given to aristocrats, clergy, and nobles. Falconry, equipment, and trained falcons, also played a role in politics. In the 14th century, the royal fief gifts sent every year by the Order of Teutonic Knights of Mary to Polish kings included 18 fine trained falcons. In 1584, Mateusz Cyganski published in Polish a book on bird hunting, which describes ways to hunt different species of birds, as well as methods of training birds of prey for falconry. The revival of Polish falconry started in the 1970s; in 1972, Gniazdo Sokolnikow of the Polish Hunting Association was created and falconry was legalized.

Falconry in Canada, USA, and Mexico

The nature of the early American settlers and their struggles to establish themselves militated against the practice of falconry. Despite their desperate struggle just to survive, we do find at least one record of falconry among the initial settlers; in 1622 an attorney, Thomas Morton, arrived in New England and left in his writings accounts of hawks and falconry in the New World. Subsequently, in the 1650s, a Jan Baptist sent back to Holland for his falcon and flew her at quarry in the Hudson Valley. Even farther south, there is an allusion to the hawk trained by one of Cortez’ captains early in their stay in the Valley of Mexico.

Of all those early Europeans in North America, falconry might most logically have been found among the Spanish in Mexico. Falconry, on the wane in Spain, still represented a legitimate and “noble” pastime for these nouveau elites in Mexico. The first Viceroy of New Spain, Velasco, had a falcon so tame that he rode with her unhooded on his fist. His son, Luis de Velasco II, employed a royal falconer to look after his birds.

American falconry in the Twentieth Century: Colonel R. L. “Luff” Meredith is recognized as being the “father” of American falconry. Among other notable figures were Dr. Robert M. “Doc” Stabler, Alva Nye, the twin brothers, Frank and John Craighead, and Halter Cunningham.

In the 1940s they formed the Falconers’ Association of North America, which ceased due to the Second World War. These men possessed the traditional bird of falconry, the peregrine. The peregrines were taken from local eyries, but falconry for them in those early years was mere possession of hawks, because they did not advance to the stage of hunting game until much later for some of them. Their countryside was not suitable for longwing falconry.

Though Meredith had visited British and European falconers, and the Craigheads spent several months hawking and hunting with an Indian prince, actual hawking for the most part escaped these men as the logical step after training a bird. In the 1960s, after the founding of the North American Falconers Association (NAFA), true game hawking exploded across the continent and the ubiquitous red-tailed hawk became a mainstay, and a decade later the Harris hawk was “discovered”.

In Mexico, Guillermo José Tapia was the president of the Asociación Mexicana de Cetrería, formed in the 1940s. Later, in 1964, Robeto Behar became involved in falconry and had the opportunity to travel and contact international falconers—Renz Waller, Kinya Nakajima, and Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente.

Falconry in South Africa

Falconry’s most recent expansion has been to South Africa, where it went with colonists. Of the 59 diurnal raptors, 31 species have been flown for falconry purposes with variable success and game birds include guinea fowl, francolin, quail, sand grouse, and duck. Furred quarry includes scrub hares and spring hares.

There is evidence of an ancient culture, with an economy based on agriculture and trade in gold and ivory. There was pre-Islamic Arabic influence on the earlier ruins and trade existed with outsiders, including India, China, and Persia. The largest of the stone complexes is The Great Zimbabwe in the center of Zimbabwe, near the town of Masvingo. In the site museum is a metal object identified as an “Arab Falconry Bell” and several soapstone birds found within the ruins.

In modern times, falconry was imported to Southern Africa by a widely dispersed group of individuals who came from different origins and settled in different areas. W. Eustace Poles is the earliest, settling in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) in the early 1950s. Heinie Von Michaelis was an immigrant to the Western Cape from Germany, at much the same time and his contemporary, David Reid Henry, the well-known bird artist, settled in Southern Rhodesia (Now Zimbabwe) in the 1960s.

Rudi De Wet was one of the first falconers in the Transvaal region of South Africa. He was a Methodist minister and learned about falconry while studying Chinese in an effort to become a missionary to China. He put theory into practice and became a focus for youngsters in the area who wanted to take up falconry.

Falconry became more formalized and experience was gained with indigenous birds like black sparrowhawks, redbreasted sparrowhawks, passage lanner falcons and African hawk eagles. The first African peregrines were obtained and efforts were started to breed these. The lack of structure was recognized and the Zimbabwean (Rhodesian), Transvaal, and Natal Falconry Clubs were formed.

The South African Falconry Association was formed in 1990. Falconers in Southern Africa have striven to develop good relations with raptor biologists, conservationists, rehabilitators, and amateur bird watchers. This has laid a good foundation for falconry today. Ron Hartley was a powerhouse in the development of falconry in Zimbabwe and is largely responsible for the good standing of falconry in the sub-region. Today, there are 186 South African Falconers and the 35 Zimbabwean Falconers.

Media Attributions

- IAF 1

- IAF 2

- International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey. https://iaf.org/a-history-of-falconry/ ↵