About Falcons

9 Conservation

Lauren Weiss

Conservation

Conservation is the act of protecting nature so it will be around in the future.

This is important when talking about peregrine falcons, since they were endangered for many years and were even extirpated, or wiped out, from eastern North America during the mid-1900s.

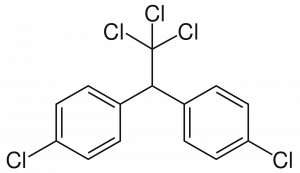

DDT

The reason peregrine falcons became endangered was DDT. DDT, or dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, is a synthetic chemical, which means that it was made in a lab.

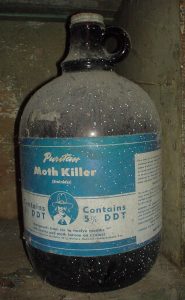

It was first synthesized in 1874 by Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler, but it wasn’t until 1939 that Swiss chemist, Paul Hermann Müller discovered DDT’s use as an insecticide, a substance that could be used to kill insects. Since there were a lot of diseases people were getting from insects, such as malaria and typhus, this was an important discovery. DDT was used in the second half of WWII to limit spread of these insect-borne diseases among civilians and troops, and was made available to the public in the United States by October 1945, where it was promoted for use as agricultural and household pesticide. Müller actually won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1948 for this seemingly very useful discovery.

|

|

DDT and the Environment

Although DDT did seem to help with controlling the insect population, it actually did a lot more harm than good. When DDT was sprayed on farmers’ crops, marshes, and other areas to control insect infestation, small birds would eat the DDT-contaminated insects, and then larger birds would eat those smaller birds. As a result, the amount of DDT in each step of this food chain became more and more concentrated. This is called biomagnification.

Biomagnification of DDT affected peregrine falcons and their ability to lay eggs. Since DDT prevented the falcons from getting enough calcium, the shells of the eggs they laid were too thin and broke before hatching. This happened to many birds of prey, including eagles, condors, and ospreys, and caused their populations to decline rapidly. By the 1960s, peregrine falcons had completely disappeared from the eastern US and large areas of the western US.

Opposition to DDT

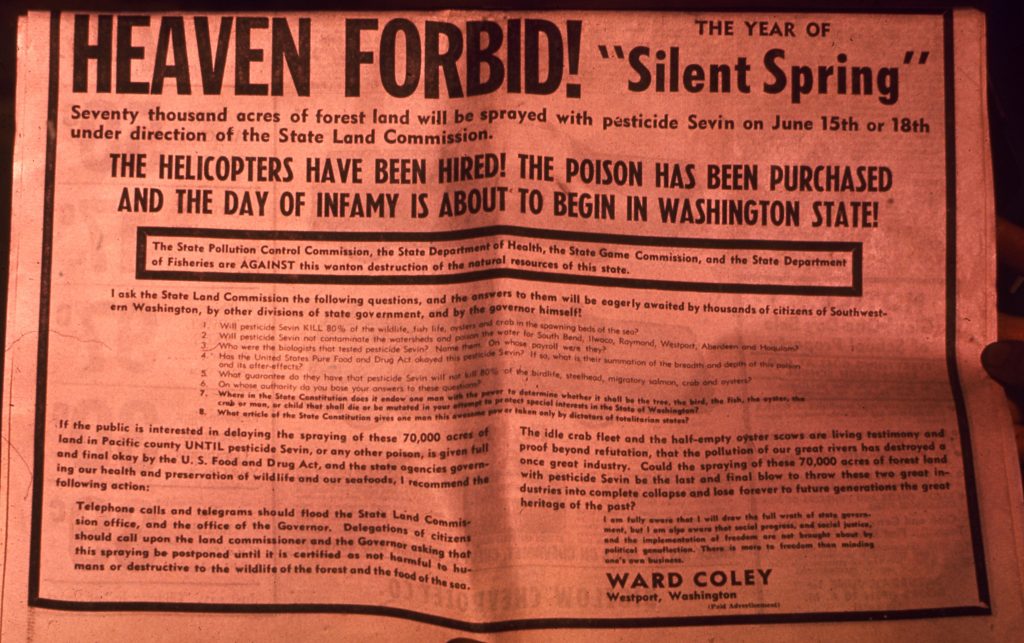

Rachel Carson was an American marine biologist, writer, and conservationist who realized the harm that DDT was doing to the environment. In 1962, she published Silent Spring: a book that documented the harm that synthetic pesticides like DDT did to the environment and humans. She did a lot of research for this book, speaking to farmers, scientists, and government workers, and concluded that pesticides must be used responsibly and as little as possible. She also accused the chemical industry of spreading disinformation and propaganda, and public officials of agreeing with it, so that people would not know that pesticides were harmful; that way, the public would continue to buy the companies’ products.

Once the book was published, it brought this problem to the attention of the public in a widespread way that had not been done before. It received fierce opposition from the chemical industry, which threatened to sue Carson’s publisher and tried to discredit Carson, making false statements about her not being qualified to speak about biochemistry and that she was a communist.

However, this strategy backfired on the chemical industry; it only drew more attention to Carson and her book. This led to a CBS television special on April 3, 1963 called The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson. This special, in turn, led to a congressional review of pesticides and the President’s Science Advisory Committee to release publicly a pesticide report on May 15, 1963 for which Carson herself provided testimony.

Silent Spring was what really started the environmentalism movement of the 1960s. Environmentalism is support for the environment and laws and other actions that protect it. In 1967, the Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit nonpartisan (not belonging to any political party) environmental advocacy group, was formed. Then, in 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created by the Nixon administration to develop official laws and policies to protect the environment.

Thanks to the efforts of groups like the Environmental Defense Fund and the Environmental Protection Agency, by 1972, the use of DDT was banned except in emergency cases.

Conservation of Peregrine Falcons

Bringing peregrine falcons back from near extinction in North America was a challenge.

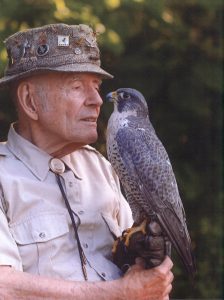

It all starts with a man named Tom Cade. Tom Cade was a falconer, field biologist, Cornell professor, and the founder of The Peregrine Fund.

Cade became interested in falconry at 9 years old after reading an article in the 1937 National Geographic magazine, “Adventures with Birds of Prey,” by John and Frank Craighead. He decided to become a falconer, or someone who keeps, trains, and hunts with falcons.

Cade used techniques he learned from falconry to help restore the peregrine falcon population. One of these techniques is called hacking. The name for this technique comes from the old English word “hack,” meaning “wagon.” In Elizabethan times, falconers put these wagons on top of hills with falcon chicks who haven’t fledged yet. They would leave food for the chicks and allow them to fledge and gain flying experience before they were recaptured and trained for falconry.

Cade took the concept of hacking and changed it a bit so that instead of recapturing the falcons, the falcons would just be allowed to go free once they fledged. This way, the chicks would be fed and protected with minimal human contact until they were able to fly off on their own.

Cade worked with SUNY New Paltz Professor Heinz Meng, who was the first person in North America to breed peregrine falcons successfully in captivity, to get the chicks he would put in the hack towers. This technique has saved many species since Cade developed it, including bald eagles.

In 1970, Cade founded The Peregrine Fund at Cornell because people kept sending in checks to Cornell to help with the efforts to save the peregrines. The Peregrine Fund is now the world’s most important raptor conservation organization.

In 1980, 3 pairs of Cade and Meng’s captive-bred peregrines nested and produced 6 chicks in the wild. This was the first natural reproduction of peregrines east of Mississippi in over 20 years! Since then, the peregrine falcon population has increased 5-10% a year.

By 1999, the peregrine falcon’s recovery was considered complete, and it was officially removed from the Endangered Species List.

Local Information: Massachusetts

The Pioneer Valley was part of those early peregrine falcon conservation efforts. As a matter of fact, chicks from The Peregrine Fund were released on Mt. Tom between 1976-1979: one of the first release sites for these falcons.

In the 1980s, Dr. Curtice Griffin, a professor in the Department of Environmental Conservation at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Dr. Tom French from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MassWildlife) were in communication with Tom Cade at Cornell. They had the opportunity to get some falcon chicks from The Peregrine Fund and hack them at UMass Amherst.

Griffin and French then got in touch with Richard Nathhorst from the Physical Plant at UMass Amherst, who was very eager to get the project going. Nathhorst convinced the director of the Physical Plant to accept the project proposal because having peregrine falcons on campus would help control the area’s huge pigeon population, especially because UMass Amherst was spending over $100,000 a year to clean and fix the damage caused by corrosive pigeon poop (see Prey and Hunting).

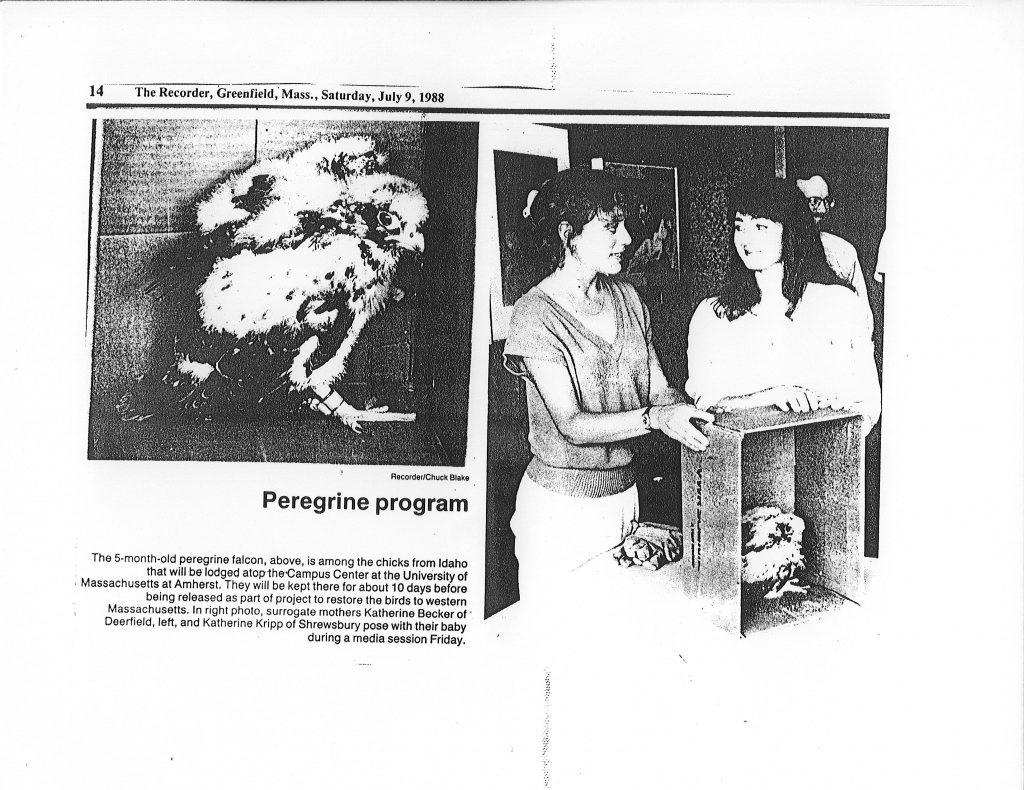

In 1988, 5 chicks from The Peregrine Fund in Boise, Idaho came to UMass Amherst. A hack site was set up on the 13th floor of the Lincoln Campus Center. The chicks were raised and monitored with minimal contact by Kate Doyle ’90, G’97 and Katherine Kripp ’90, G’97 (then biology graduate students). They fledged in July and didn’t return.

In March of 1998, the first nest box built by Chris Davis of New England Falconry and David Ziomek, then director of the Hitchcock Center, was given to Nathhorst and installed on top of the W. E. B. Du Bois Library. That year, an adult falcon was seen going in and out of it. In May of 1999, a nesting pair was seen flying frequently to the box with prey. In 2001, eggshells were found in the box. In 2003, the first chick (unbanded) officially seen fledged. In 2004, the first banded chicks fledged.

In 2012, a livestream camera and camera arm were installed on the roof, broadcasting the falcons’ nesting season to the public.

In 2022, a new nest box was installed on the Library roof; while it was being renovated, the falcons nested in an old box on Thompson Hall (also built by Davis and Ziomek) that had not been used prior to that nesting season.

In total, over 50 chicks have successfully hatched at UMass Amherst.

Media Attributions

- DDT Chemical Structure © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Paul Hermann Müller © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- DDT Jug © Jolomo is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 5574122257_0c7f1af45d_o © Crossett Library is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 32213742634_3ef5466346_h © R.B. Pope is licensed under a Public Domain license

- image2 © Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Rachel Carson © U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 35125492502_e42fb928a2_4k © USDA Forest Service, Region 6, State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tom_Cade © The Peregrine Fund is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Professor Heinz Meng © SUNY New Paltz is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Private: “The Recorder” Peregrine Falcon Articles © The Recorder is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license