About Falcons

10 Peregrine Falcon Subspecies

Lauren Weiss

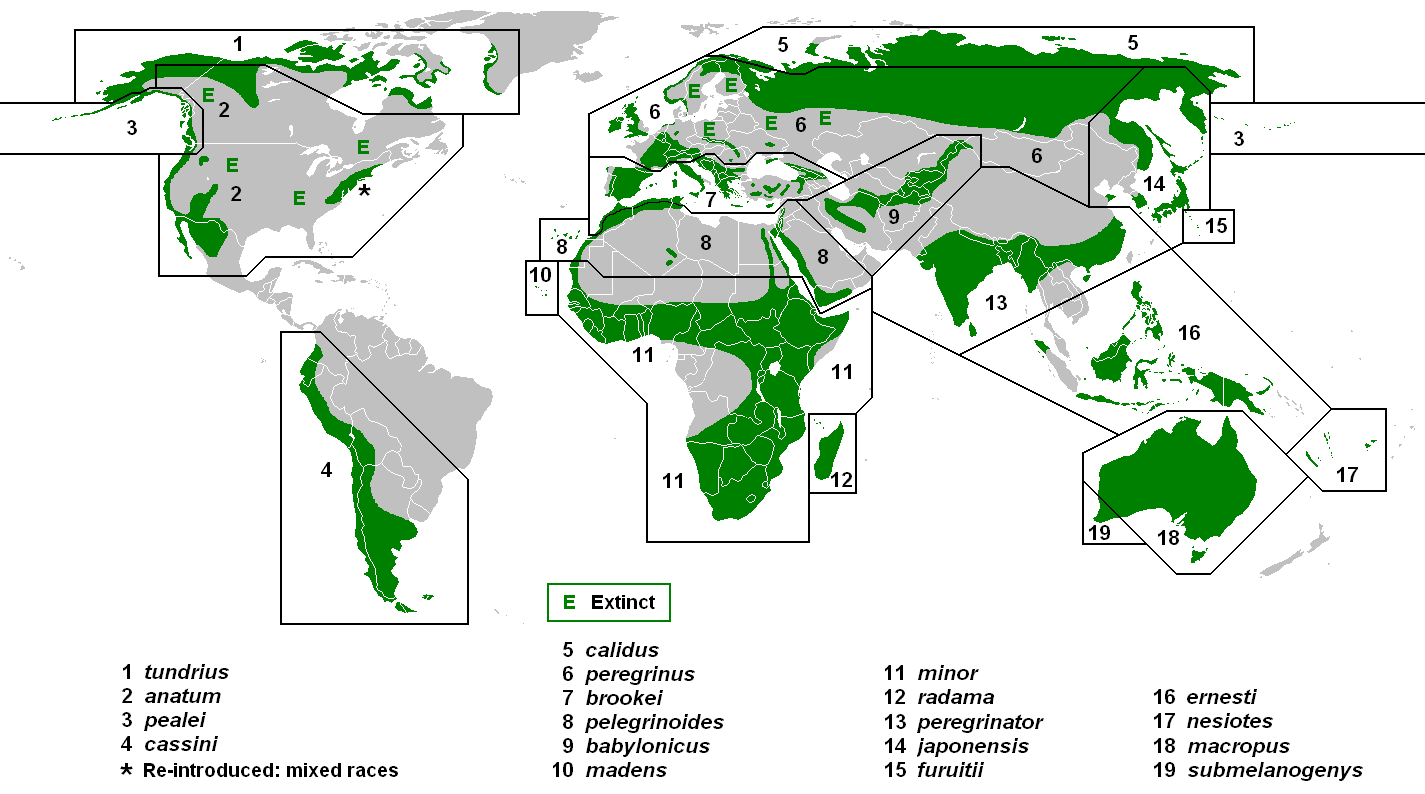

Since peregrine falcons can be found all over the world, there are many different variations of them. Currently, they are referred to as subspecies. A subspecies is a classification rank below species used to describe populations of a species that live in different areas and have different physical characteristics, but are still able to interbreed. Although there is some disagreement in how peregrine falcon subspecies are named and classified, here are descriptions of the subspecies as they currently stand.[1]

Here is a map showing the locations where the various subspecies are found.

1. Tundrius

(North) American Tundra Peregrine

Falco peregrinus tundrius

Name

Although there are descriptions matching the North American tundra peregrine dating back to the 1600s from European falconers in America, this subspecies was not formally described until 1968: the last peregrine subspecies to be formally recognized. It was named by C. M. White in 1968. “Tundrius” (TUN-dree-uhs) means “comes from the tundra.”

Habitat

Tundrius is found in North America north of the tree line, so in upper North America in areas like northern Alaska, northern Canada, and southern Greenland.

They mostly nest on cliffs and bluffs, but will also nest on pingos (hills with ice cores), gravel banks, lake shores, some abandoned stick nests, and human-made structures.

They tend to migrate long distances during the winter. They mostly migrate to southerly areas on the east coast, the Gulf Coast, and even eastern Mexico, but have also been spotted by the Great Lakes, west coast, and western Mexico. Some also go even further into South America as far as southern Chile.

The most common prey of North American tundra peregrines are passerines and shorebirds, both in their breeding grounds and in wintering grounds. In their breeding grounds, some will also prey on small mammals like lemmings and Arctic ground squirrels. In their wintering grounds, they also prey on bats.

Average Appearance

Tundrius is similar in appearance to calidus, and is paler in color than anatum. In fact, some tundrius found near the Arctic are extremely pale in color. In general, their undersides have a more yellowish tint, unlike the reddish tint of anatum. Their malar stripes are also narrower, and sometimes have a stripe that almost connect that patch of color to the color at the back of the head. They also have narrower wings than the other two North American subspecies.

2. Anatum

(North) American Peregrine

Falco peregrinus anatum

Name

The first formal listing of this name was by Charles Lucien Jules Laurent Bonaparte (Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew) in his 1838 book, Geographical and Comparative List of Birds of Europe and North America (although the subspecies itself was first described in Alexander Wilson’s 1814 book, American Ornithology). The name “anatum” refers to the Latin word “anas” for “ducks,” and this subspecies was once commonly called the duck hawk.

Habitat

Anatum is found throughout many parts of North America from Alaska’s northern taiga to eastern Canada, down through the U.S., and south into Mexico.

They used to nest mostly on cliffs, although some did nest in tree cavities and abandoned stick nests. Nowadays, they frequently nest on human-made structures, partially due to the reintroduced populations being released at such sites.

Anatum from regions that freeze over or from which their prey migrates will also migrate. They migrate southwards; some travel long distances to South America. Before extirpation, eastern American peregrines used never to migrate farther south than central Georgia.

Although the American peregrine varies in region, and, therefore, so does their prey, they generally tend to prey on pigeons and doves, especially urban peregrines.

Average Appearance

There are three different geographic groups of anatum: eastern, western, and boreal forest/taiga.

The eastern American peregrine (“rock peregrine”) was extirpated due to the use of pesticides in the mid-1900s. The conservation and repopulation effort for that region included introducing captive-bred peregrines from different subspecies, including tundrius, western anatum, pealei, macropus, cassini, peregrinus, and brookei. The resulting new population in the east tends to have dark facial coloring, a pale reddish tint to the breast, and barring underneath.

The western anatum is generally smaller, with a stronger reddish tint to the breast and a brownish tint to its bluer back color.

The boreal forest/taiga anatum is generally larger, more slender, and more lightly colored than the western American peregrines.

3. Pealei

Peale’s Peregrine

Falco peregrinus pealei

Name

The Peale’s peregrine was formally recognized by Robert Ridgway in 1873. He named it after the 1800s collector, Titian Ramsay Peale (son of Charles Willson Peale, the well-known Philadelphia museum owner).

Habitat

Pealei is found along seacoasts from the Commander Islands through the Aleutian Islands and along the coast of Alaska. They are highly adept at traveling and hunting at sea, even in thick fog.

It typically does not migrate.

Its habitat has a limited prey selection. Pealei mostly prey on alcids (“web-footed diving birds with short legs and wings”[2]).

When these peregrines hunt at sea, they use what is called “ground effect,” which is “the increased lift and reduction of drag resulting from compressed air when within one wingspan of the sea’s surface.”[3] This helps them fly low over the sea and surprise attack their prey. They will also do the usual peregrine stoop in mid-air, and then retrieve the prey after it falls into the water.

Average Appearance

There are at least two subgroups of pealei.

The first is an Aleutian form found in the outer Alaska Peninsula (Shumagan Island, etc.) westward through the Aleutians to the Commander Islands. These pealei have spots on their upper breasts, crops, and throats that are round or shaped like teardrops. Their undersides have a dirty white color with a gray tint. Their backs are dark lead/slate-colored. Their legs and feet are paler yellow than other subspecies.

The second subgroup (“Haida Gwaii”) is found in the southern part of the pealei range up to at least Cape Spencer and Icy Point, Alaska. These pealei have less bold spots and barring. Males’ crops are usually white and only have slight streaks. Females usually have wide, whitish bands on their foreheads.

Peale’s peregrines also have a relatively short middle toe in comparison to other subspecies of peregrines, possibly because of the types of prey they catch and that shorter toes retain heat better in colder environments.

4. Cassini

South American Peregrine

Falco peregrinus cassini

Name

This peregrine was named by Richard Bowdler Sharpe in 1873. He named it after John Cassin, who had described what we now know to be this subspecies in 1855 (although Cassin called it Falco nigriceps). According to White, Cade, and Enderson, cassini in this case is pronounced “CASS-in-ee,” not “cuh-SEE-nee.” This peregrine has also been referred to as the “Austral peregrine,” from the Latin austrālis (“southern”), even though there are several subspecies of peregrine falcons that are found in the southern hemisphere.

Habitat

Cassini is located in South America. There are a few subgroups within this subspecies.

There is a group located in the Fuegian region and the Falkland Islands.

Another group is found from central Argentina up through Bolivia and along the Pacific coast and Chile.

Another group is found in northern Chile, Peru, and Ecuador.

Cassini does not migrate.

Average Appearance

In general, South American peregrines have dull black heads, blue-black backs, and bluish rumps. They have broader, more extensive, wavy barring across their breasts and bellies than North American peregrines. They have a grizzled-gray look to their lower undersides.

The Fuegian region peregrines are the largest and darkest.

The central Argentina peregrines are smaller and have more reddish than tawny undersides.

The northern Chile peregrines are even smaller and have paler backs.

Pallid Variant

There is a “pallid” (pale) variant of cassini. It used to be considered a separate species, called the Pallid Falcon or Kleinschmidt’s Falcon (Falco kreyenborgi). Their leucistic pale coloring is a genetic trait, possibly the result of natural selection during the Ice Age, where the shifting of coasts and continents produced a climate that favored the pale coloring. Pale variations of species are not completely uncommon, especially near the edges of that species’ habitat range.

The pallid variant of cassini is lighter in color than regular cassini. It ranges from extremely light, with white breasts and very pale bluish backs, to intermediate, with light barring, cream coloring, and a darker back. All of them have white, unmarked undertail feathers and a peach tint to the back. Their talons and bills are white-yellow with gray tips.

5. Calidus

Siberian Tundra Peregrine

Falco peregrinus calidus

Name

This peregrine was first mentioned in 1788 by John (Joannis) Latham in his book, A General Synopsis of Birds. He later formally described it in 1790 in another book, Index Ornithologicus. “Calidus” (CAL-ih-duhs) is a Latin word referring to something fiery. Latham named it this way because he got the specimens he used for the descriptions from India, which can be a hot environment. However, this subspecies only migrates down there during the winter; it regularly lives far up north. That is why there has historically been some disagreements on this falcon’s Latin name; some wanted to call it leucogenys (“white cheeks”) instead of calidus, because it seems to fit the bird more accurately. However, due to the International Code of Nomenclature (Berlin, 1901), which is a set of rules and recommendations on how to name species, Latham’s name is used because he was the first to name it (the Code’s “rule of priority”), and calidus is also the name that was used for this subpsecies most frequently (the Code’s rule of “history of usage”).

Habitat

Calidus can be found in the Eurasian tundra west to east from the Kanin Peninsula and the eastern boundary of the White Sea to the Jana River basin region, and, from the northernmost region, southwards to the Yenisey (Jenisei) River valley. It can also be found on major islands in the Barents, Kara, and Laptev Seas, including the southern part of Novaya Zemlya; however, it is not found on Wrangel Island.

It usually nests along rivers, and some on lake shorelines. Some will even use old snowy owl nests.

Calidus migrates south- and southwestward during the winter, including to South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Prey varies for calidus, but typically includes waders and passerines. If there is a high rodent population, almost half of their diet may consist of rodents. In their winter grounds, they prey on bats, as well as other birds not found in their regular nesting grounds.

Average Appearance

Adult calidus are just a little larger than the European peregrine, but paler, especially with regard to their backs (pale bluish-gray) and crowns. Their faces have a white forehead band, narrower and longer dark malar stripes, and a wider white patch near their ear openings with no streaks. Their underside can have a yellow tint and is less marked.

6. Peregrinus

European (Eurasian) Peregrine

Falco peregrinus peregrinus

Name

The European peregrine is considered to be the nominate subspecies. This means that this particular type of peregrine falcon is the type that was first described by observers. You can tell that it is the nominate subspecies because its subspecies name is the same as its species name (peregrinus).

This subspecies of peregrine was first described in 1771 by Marmaduke Tunstall from Wycliffe, York, England in his book, Ornithologica Brittanica. This is also the first formal adoption and listing of the name Falco peregrinus.

Habitat

Peregrinus can be found in temperate latitudes West to East across temperate Eurasia from the British Isles to the Amur River region. Since this is such a large area, observers used to classify some geographical groups of this subspecies differently, such as Falco peregrinus brittanicus in the British Isles, Falco peregrinus germanicus in central Germany, Falco peregrinus scandinavie in Fennoscandia, and Falco peregrinus ussuriensis in the Ussuri River region of Asia.

It typically nests on cliffs and human-made structures. However, this subspecies will also nest in trees (taking over unused nests of other birds) and even on the ground.

In Europe, peregrinus typically does not migrate, but does migrate in Scandinavia and Asia.

Since peregrinus is found across such a large area, its prey varies, but mostly consists of pigeons.

Average Appearance

Adult peregrinus have a dark slate blue back with a paler gray rump and tail. On their faces, they have broad, pale blue to black malar stripes and white cheeks and throat. The area around where their ear openings are might have dark streaks. Their forehead is a dirty white color. Their chest has fine black spots with some streaking, and they have black barring on the rest of their underside.

Additional Information

European peregrines are the source of many aspects of the rich history of falconry. Their remains were found in the dwellings of 9th and 10th century Shetland Island Vikings, who used them for hunting. From the Middle Ages to the mid-20th century, they were heavily used and admired in falconry; people like Frederick II (known for his famous treatise on falconry), William Shakespeare, and Sir Walter Scott described them at length in their works.

Unfortunately, after the mid-20th century, they were increasingly persecuted throughout Europe for various reasons, including to preserve game for hunting and, during World War II, to reduce the loss of messenger pigeons carrying important information to troops. Additionally, like the peregrines in the United States, they also suffered from the use of pesticides.

However, thanks to conservation and the restriction of pesticides, the European peregrine population has made a comeback.

7. Brookei

Mediterranean Peregrine

Falco peregrinus brookei

Name

This peregrine was named after A. Basil Brooke, who brought some from Sardinia to the British Museum in 1869 and 1871, respectively.

Habitat

Brookei is found in southern Europe and the Mediterranean basin. It can also be found in northern North Africa and a little bit into Asia’s Koptag Mountains.

It nests from sea level (sandy knolls along beaches) to high elevations and anywhere in between. It is typically found on cliff ledges, and will even use cliffside stick nests abandoned by other birds.

It does not migrate.

The most common prey for these peregrines are various types of pigeons, especially rock doves. However, brookei in the Caucasian region do hunt bats, as well; in fact, bats can be up to 30% of their diet.

Average Appearance

Although brookei’s appearance varies throughout the region where it is found, in general, it is smaller than peregrinus with short, broad wings, dark heads, broad malar stripes, and a rusty tint to its undersides.

8. Pelegrinoides

Barbary Falcon

Falco peregrinus pelegrinoides

Name

This peregrine was first described in 1829 by Coenraad Jacob Temminck of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leyden, The Netherlands. Its name combines the English and French words for “peregrine” (“peregrine” and “pèlerin,” respectively), and the suffix “oides” (“like/similar to”). It is called the Barbary falcon because it is found in what used to be called the Barbary States (North Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to Egypt) before the 19th century. In Latin, “barbaria” means “foreigner” (later with a negative connotation, referring to pirates sailing along the coasts beginning in the 1300s).

Some experts consider this bird to be a near-peregrine, peregrine superspecies, or possibly a separate species altogether.

Habitat

Pelegrinoides is found along the southern Mediterranean region, including North Africa, the Middle East, and the Canary Islands.

Some pelegrinoides, such as those in Israel, Morocco, and the Canary Islands, do not migrate. Others, such as those in Sudan, will migrate farther south into Africa, including Kenya.

They typically nest on rocks and cliffs, but have been known to nest on human-made structures, as well.

They prey most commonly on pigeons, doves, sandgrouse, and bats.

Average Appearance

Due to its large range, pelegrinoides tends to vary in color, so much so that different regions of pelegrinoides were once labeled as individual subpsecies, including punicus (Western North Africa) and arabicus (northern Egypt-Arabian Peninsula).

On average, this peregrine’s back is anywhere between light bluish and pale blue-gray (except on the Canary Islands; those are typically darker and more of a blue-black). The amount of reddish coloring on their heads also varies, from none to a lot, including a possible reddish stripe above the eye. Their fronts are usually an off-white/peach/orange color. Male pelegrinoides have the narrowest wings according to wing width-length ratio.

Additional Information

Pelegrinoides is famous for its role in Arab falconry over the centuries.

9. Babylonicus

Red-Naped Shaheen (Red-Capped Peregrine)

Falco peregrinus babylonicus

Name

This peregrine was first described by Philip Sclater, Ibis editor, in his 1861 paper, “Capt. L. H. Irby on birds observed in Oudh and Kumaon.” It was named after Babylonia (present-day Iraq), the location where the specimen was found.

Habitat

Babylonicus is found in central Asia, from eastern Iran to the Mongolian Altai ranges.

They nest on cliff ledges as well as abandoned stick nests of other raptors.

Some migrate to north and northwestern India; they enjoy the deserts and semiarid areas.

They most commonly prey on passerines, such as rock doves, swifts, and starlings.

Average Appearance

According to White, Cade, and Enderson, there are three different groups of babylonicus: large, dark birds from western Turkmenistan through adjacent countries in middle Asia; smaller, paler birds in Iran and possibly Afghanistan; and large birds in Mongolia.

Babylonicus looks similar to pelegrinoides, except it is slightly larger and its eyes are not quite as large/”buggy”. Additionally, it generally has a more reddish color on its head and neck, the brown color on its head is lighter, and its upper and lower back do not contrast as much in color. Paler babylonicus have entirely peach/off-white heads and pale blue-gray backs.

10. Madens

Cape Verde Peregrine

Falco peregrinus madens

Name

Peregrine falcons were first seen on the Cape Verde Islands in 1902, but it wasn’t until 1963 that the first breeding pair was discovered by Abbé Réné de Naurois. The subspecies was formally described in 1963 by the Smithsonian Institute’s Sidney Dillon Ripley II and George E. Watson.

Its name comes from the Latin word “madeo,” meaning “saturated,” because it has a saturation of brown coloring on its feathers.

Habitat

Madens is the second rarest type of peregrine falcon and is considered endangered. It is found on the Cape Verde Islands off of the coast of Africa.

They do not migrate.

Average Appearance

Madens is between peregrinus and brookei when it comes to size. Its upper front has a saturated brown color over the usual pale blue; otherwise, its lower back is like peregrinus. Its head also has a brown/reddish tint, including on the back edges of the malar stripes.

11. Minor

African Peregrine

Falco peregrinus minor

Name

Charles Lucien Bonaparte (Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew) officially gave the African peregrine its name in 1850, but Hermann Shlegel was the first to give an actual description of it in 1851. The name “minor” means “small,” referring to the fact that African peregrines are, in general, some of the smallest peregrines.

Habitat

Minor is found in sub-Saharan and Southern Africa. They are rather rare, possibly due to human population increases and interference.

They usually nest on cliffs, inselbergs, and kopjes, but also nest in woodlands and South African shrubbery (Fynbos), as well as human-made structures.

They usually don’t migrate.

They mainly prey on pigeons and doves, where available, as well as passerines like starlings and near-passerines like swifts.

Average Appearance

The African peregrine is similar to the European peregrine, except smaller and darker, with black backs, white-to-reddish undersides, and dense, bold barring. Their tails often have gray-white bands. Some don’t have the white patches by their ear openings.

12. Radama

Malagasy (Madagascan) Peregrine

Falco peregrinus radama

Name

Radama was named by Gustav Hartlaub in 1861 after the newly-crowned King Radama II of Madagascar.

Habitat

Radama is found on Madagascar and the Comoro Islands, although they are not very abundant.

They typically prey on small passerines, such as weaver finches, but not really pigeons and doves.

Average Appearance

Radama looks a bit like minor, but slightly smaller and with a blacker back, whiter breast, and more, broader barring. It also has more visible white tips on its wing feather edges.

13. Peregrinator

(Black) Shaheen

Falco peregrinus peregrinator

Name

The name “shaheen” comes from the Persian “Shah” (king) and “een” (birds), so “king of birds.” The use of “ator” makes its Latin name mean “black peregrine,” although it can also be considered a superlative for peregrine, so it would also mean “extreme wanderer.” It was named by Carl Jacob Sundevall in 1837, who came across this subspecies in 1828 while sailing through the Indian Ocean.

Habitat

Peregrinator can be found from the western edge of the Tharr Desert, India and southern Sindh Pakistan across South Asia to China’s eastern coastal edge.

They often nest in abandoned raptor stick nests. They are usually found in lower elevations, but can winter in higher elevations.

They tend not to migrate, but sometimes, after breeding, they may travel to urban areas.

The most common prey for black shaheens are passerines (songbirds) and near-passerines, including pigeons, partridges, quails, and doves. They will also even prey on bats.

Average Appearance

In general, black shaheens are medium-sized and have longer middle toes than other subspecies like the European peregrine.

There are several distinct geographic groups of the black shaheen.

First, there are the black shaheens in southern India. Their heads are almost all black. Their malar stripes are more like a ski mask, sometimes with a very small pale patch around the ear openings. Their backs are solid gray with a solid ash-gray rump, and their fronts are solid chestnut to reddish-brown, except for white chins and throats. Their wings are also solid in color, with chestnut undersides.

Second, there are the northern black shaheens in the Himalayas, Nepal, and Assam. Their backs are less ash-gray and more blue, with barring. Their breasts are less chestnut and whiter in color.

Third, there are black shaheens in Myanmar and China. Their breasts are considerably whiter with wider barring Some black shaheens in China are very white in front with a light gray tint and small, narrow bars like peregrines in Eurasia.

14. Japonensis

Eastern (Japanese) Peregrine

Falco peregrinus japonensis

East Siberian Peregrine

Falco peregrinus harterti

Name

In Peregrine Falcons of the World, White, Cade, and Enderson group japonensis and harterti together because “few agree that they are distinct and putative subspecies.”

Japonensis was first described by Latham in his 1788 book, General Synopsis of Birds as a “Japonese [sic] Hawk,” since it was found on Captain James Cook’s ship during his 1779 voyage, but it wasn’t officially given its Latin name until 7 years afterwards by Professor Johann Friedrich Gmelin.

Harterti was named by S.A. Buturlin in 1907, who found falcons in the Kolyma region of Siberia that were lighter than the Japanese peregrine but darker than the Siberian tundra peregrine. He named it after Ernst Hartert, a German falcon worker.

Habitat

Japonensis is found throughout Japan southwards from Hokkaido to Kyushu and Tokara Islands, Kagoshima Prefecture.

It is often found on cliffs, either by the sea or more inland.

Harterti is mostly found in the Chukotka Autonomous Region (Chukchi), Koryakski Autonomous Region, and the Kamchatka Peninsula, as well as parts of the mainland Chukchi Peninsula.

It nests in lowlands, such as along rivers on the Chukchi Peninsula, as well as mountainous areas higher up.

Both of these subspecies have been found flying over the oceans of their respective locations.

Harterti populations in the north and some japonensis migrate southwards (China, Southeast Asia, and India), but some japonensis from northern Japan, as well as some harterti spotted on the south coast of the Chukchi Peninsula where ducks were plentiful, do not migrate.

The most common prey in Japan for peregrines are pigeons. Brown-eared bulbuls are also a common prey item. These peregrines that nest along the shorelines will also commonly prey on shorebirds, like red phalaropes and pectoral sandpipers.

Average Appearance

Japonensis are darker than harterti and peregrinus, but their barring is still visible. They have slate-gray backs, with darker heads and shoulders and lighter rumps. Females tend to be darker than males. Their undersides have a pale yellow, olive green, or pink tint; males’ bellies tend to be whiter than females.

Harterti are darker than calidus. They also have dark heads and shoulders and paler backs, but the contrast between them is more distinct. They also have a smaller white area around their cheeks and broader “sideburns.” They have barring on their lower undersides shaped like crescents, spots, and teardrops; their upper undersides are usually clearer.

Additional Information

Peregrine falcons have been documented in Japan since as early as the 16th century. They were used in falconry, but not nearly as much as northern goshawks or mountain hawk-eagles, since those birds performed better in forest environments and were easier to trap.

An interesting point is that the Nakajima Ki-43 fighter aircraft used during World War II was called Hayabusa, which means “peregrine falcon” in Japanese.

15. Furuitii

Iwo Peregrine

Falco peregrinus furuitii

Currently, there are no known photographs of living furuitii.

Name

This peregrine was named by Tokuutaro Momiyama in 1927 after Mr. I. Furuiti, the gentleman who obtained the specimen for him. In Japanese, it is called “Shima-hayabusa” (“Island Peregrine”).

Habitat

This is the rarest subspecies of peregrine falcon, and little is known about it. It is found on the Iwo Islands group south of Honshū, Japan, although it could possibly be extinct. None have been decidedly spotted on the islands since World War II.

Average Appearance

Furuitii is smaller than pealei and has a blacker head and tail, as well. They have relatively long tails compared to wing length.

A few distinct characteristics (of juveniles) as noted by White, Cade, and Enderson that distinguish them from nearby subpsecies include: juveniles have a wider variation of color and markings than what would be expected for an isolated population; juveniles do not have lighter edges on their dorsal feathers like nearby Asian peregrines; and juveniles have a more reddish tint to their undersides, unlike japonensis and pealei.

16. Ernesti

Ernest’s Peregrine

Falco peregrinus ernesti

Name

This peregrine was named by Richard Bowdler Sharpe in 1894 after Ernest Hose, who collected the specimens he described.

Habitat

Ernesti is found off the coast of southeast Asia, including the Sunda Islands, Philippines, Malaysia, eastern New Guinea, and the Bismarck Archipelago.

They nest on high cliffs on the islands, typically around where volcanic activity used to take place, since such activity produced many craters and ledges they can use.

They prey most commonly on pigeons, doves, parrots, swifts, and even bats.

Average Appearance

Ernesti is the darkest-colored subspecies of peregrine falcons. Their heads are fully black without any pale forehead stripes; the malar regions appear squared off and connect directly to the black on the back of the head. Their backs are also black, almost purplish-black. Their underparts have a grayish tint.

17. Nesiotes

Island (Melanesian) Peregrine

Falco peregrinus nesiotes

Name

This peregrine was first described in 1941 by Ernst Mayr, who worked at the Museum of Natural History in New York. The name comes from “nesos,” which is Greek for “island,” and “nesiotes” means “insular.”

Habitat

Nesiotes is found on New Caledonia, Vanuatu, and Fiji; however, it is not overly common.

They typically nest on cliffs along the coast and on mountains more inland.

They do not migrate. As a matter of fact, genetics suggest that there is no interbreeding between the peregrine populations of each of these islands, or between nesiotes and any other peregrine subspecies nearby.

Prey depends on where they are nesting (coast, grasslands, or tropical forests), but includes parrots, doves, bats, pigeons, and seabirds/shorebirds.

Average Appearance

Nesiotes is a very dark peregrine with lots of markings. Their heads, shoulders, and upper backs are more soot-colored than macropus, while their lower backs are more blue than black and have more barring than ernesti. Some coloring varies depending on their location: New Caledonia and Vanuatu nesiotes have whiter crops than Fijian nesiotes, and that white color extends into the upper breast. Fijian nesiotes have spots on their upper breasts, as well as a darker reddish tint to their breasts than those from New Caledonia and Vanuatu.

18. Macropus

Australian Peregrine

Falco peregrinus macropus

Name

William Swainson was the first to describe macropus in his 1838 work, “Two centenaries and a quarter of new or little known birds.” This work was published three months before Gould’s, which is why macropus is used over melanogenys. Macropus translates to “big foot,” referring to the large feet of this subspecies.

Habitat

These peregrines are found in Australia, except in the southwest.

They mostly nest on cliffs, but also nest in urban areas on buildings, dams, quarries, powerline polls, etc., and unused stick nests of other birds (in trees and some even underground!).

They do not migrate.

When not near coastlines, these peregrines prey on parrots, as well as pigeons and European starlings.

Average Appearance

White, Cade, and Enderson group macropus and submelanogenys together.

These peregrines have black cheeks and proportionally large feet. They typically have white crescent-shaped patches that frame their black cheeks. Their upper breasts are mostly not marked, but they have barring on their lower breasts and bellies. They are also noted to have bills with more arc and depth to make it easier for them to hunt prey like parrots.

19. Submelanogenys

Black-Cheeked Peregrine/Southwest Australian Peregrine

Falco peregrinus submelanogenys

Name

Gregor M. Mathews was the first to describe the black-cheeked peregrine in his 1912 book, The Birds of Australia. He chose the Latin name as a version of melanogenys (“black cheeks”), which came from John Gould’s name for peregrines in Australia in 1838.

Habitat

These peregrines are found in southwest Australia.

They mostly nest on cliffs, but also nest in urban areas on buildings, dams, quarries, powerline polls, etc., and unused stick nests of other birds (in trees and some even underground!).

They do not migrate.

When not near coastlines, these peregrines prey on parrots, as well as pigeons and European starlings.

Average Appearance

White, Cade, and Enderson group macropus and submelanogenys together.

These peregrines have black cheeks and typically have white crescent-shaped patches that frame their black cheeks. Their upper breasts are mostly not marked, but they have barring on their lower breasts and bellies.

Media Attributions

- Peregrine Subspecies Map © MPF is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Falco Peregrinus Tundrius © Brian Stahls is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Anatum © UMass Amherst Libraries is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Falco Peregrinus Pealei © nmrvelj is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco peregrinus cassini © Julian Rolando Tocce is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Cassini, Pallid © Thomas Gibson is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco peregrinus calidus © Игорь Поспелов is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Peregrinus © Richard Hasegawa is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Peregrinus © Riccardo Molajoli is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco peregrinus brookei © Daniel Raposo is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Pelegrinoides © Miquel Rafa is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Babylonicus © Avinash Bhagat is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Minor © John Gale is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Radama © lemurtaquin is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Peregrinator © Afsar Nayakkan is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Falco Peregrinus Japonensis © misooksun is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Ernesti © Wich'yanan L is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Falco Peregrinus Nesiotes © Pierre-Louis Stenger is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco Peregrinus Macropus © fubberpish is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Falco peregrinus submelanogenys © Stephen Buckle is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- White, Clayton M., Tom J. Cade, and James H. Enderson. Peregrine Falcons of the World. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2013. ↵

- Merriam Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/alcid ↵

- White, Clayton M., Tom J. Cade, and James H. Enderson. Peregrine Falcons of the World. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2013. 185 ↵