Abby Bates

Identity Crises Galore (And So Much More)

A few years past, I told my optometrist I wanted to be a writer. This wasn’t unusual; I’ve told a lot of people that I wanted to write, and Dr. Talusan, being Filipino like my mom, had always been more grandfatherly than professional, giving us contacts and even eye exams gratis by virtue of our shared heritage. He’d had dinner with my family and played golf with my grandfather—an esteemed doctor like him, raised in extreme poverty and the horrors of the Japanese occupation. When he asked about my life and loved ones (and he always asked about my grandfather), it wasn’t an act of empty, professional courtesy.

“My daughter teaches creative writing at Tufts,” he said, scribbling her name on a piece of prescription paper. I grinned and thanked him, squeezing his leathery brown hand. Filipinos always feel an instant connection with one another. Strangers can be rendered family upon first meeting; lifelong bonds are forged in the blink of an eye. Our culture, overshadowed, and suppressed at times, defined by the Western world and centuries of colonialism, immutably binds us. Yet as he offered a smile of his own, Dr. Talusan said what I most dread to hear from anyone fully Filipino: “She’ll like you, even though you’re only half.”

“Even though you’re only half.” A complete thought, if not a complete sentence, which told me that I wasn’t complete myself. A cruel and hideously familiar caveat. Tears pricked my eyes. I lifted my gaze to the industrial light fixture as if weak and distant heat might evaporate the moisture, stem the tide of unwelcome emotion. I felt like a fist to the kidney that sense of agonizing alienation that comes with being biracial. I was a daughter of two worlds at once, and yet, I had no world of my own. Nothing quite suffices like a cliche to describe it.

By and large, multiracial people are well acquainted with identity confusion and discrimination. While the fastest-growing demographic in the United States, “growing at a rate three times as fast as the population as a whole,” we are also an incredibly lonely one, never quite knowing where we belong in a society that favors rigorous, stifling categorization (Parker et al.). Studies have found that multiracial people experience poor psychological health when we struggle to forge our social identities at complex racial and cultural crossroads, particularly when others call our backgrounds into question. Too common are the microaggressions that reinforce our insecurities, comments delivered in blithe ignorance, which compound over time to cause us “a great amount of psychological distress” (Nadal et al. 191). Often, multiracial people feel pressured to “choose sides,” a harmfully reductive binary complicated, or perhaps unconsciously encouraged, by lifelong invalidation from family, peers, and strangers alike (Gaither 114). We may feel—or be constantly told—that we are “too Asian” to be white or “too white” to be Asian, or any combination of too much of one race to be another, and vice versa. It’s almost as if we have no claim on our identities at all.

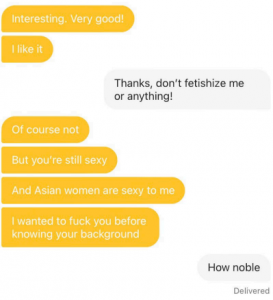

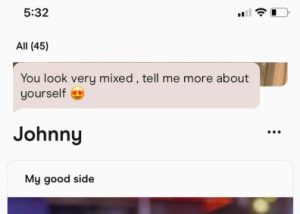

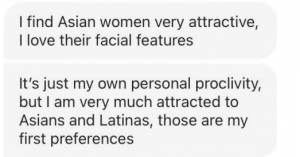

Thus, languishing in the liminal spaces of multiracial existence, many suffer from racial impostor syndrome, which occurs “when an individual’s own sense of their racial…identity doesn’t fit with how others perceive them,” leading to insecurity and feelings of isolation from family and community (Salhany). To be sure, never do I feel more white than when I try to wrap my tongue around the Tagalog phrases uttered by my mother’s kin. Frequently, I wonder whether I even have a right to talk about the racism I’ve experienced when I’m half white and overall racially ambiguous—though the latter has, in truth, rendered me subject to quite a colorful array of discriminatory behaviors, like a grocery clerk demanding to know whether I’m Mexican because I bought tortilla chips, or men telling me how much they love sexually dominating [Insert Wrong Type of East Asian] girls—or, better yet, [Half-White, Half-Insert Wrong Type of East Asian] girls. I’m certain it’s not difficult to imagine what a nightmare dating apps can be.

There was that time a woman approached me in a restroom speaking rapidly in Spanish. When I replied, “er, no habla español,” she inquired in English whether I was Colombian. Once more I replied in the negative, shaking my head while I essayed to maintain a polite amount of eye contact. Imagine my astonishment when she told me I was beautiful, embraced me with a kiss on each cheek, and took her leave. My vanity occasionally lets me look back on this memory with fondness, yet I must confess that even my “pleasant” encounters with microaggressions leave me feeling othered, objectified, and oddly incomplete. Privately, I’ve taken to calling these feelings “disbelonging,” as the prefix “dis,” meaning “not or none,” suggests nonbeing and perpetual alienation.

Journalist Kristin Wong, born to a Chinese mother and a white father, describes a similar experience:

My identity has become more a grab-bag of customs. And it’s not just what I do. It’s what I look like as well: Random strangers feel comfortable telling me ‘You don’t look super Chinese’ or even ‘Nah, you’re just white.’ When you’re multiracial, people feel like they can pick your identity for you. They try to pin down your background like it’s a wine tasting tour — I’m detecting notes of Italian. Ooh ooh! Don’t tell me, just let me stare at you harder until I get it right.

Sarah Gaither of Duke University found that when applying for a driver’s license in North Carolina there was no biracial option. When faced with having to choose between identifying as white or Black instead of both, she ended up with “an empty space next to race.” Indeed, as Wong goes on to note, “that’s how it feels to be biracial — like you’re nothing” (Wong). I have filled out countless forms that seem to deny—or outright reject by dint of a lack of options, which sometimes feels intentional—the very existence of multiracial people, of me.

Contextualizing History and a Truly Lamentable Dearth of Research

And it never ends. Recently, while supplying information for my new healthcare plan, Harvard Pilgrim presented the categories of “race” and “secondary race.” This called to mind the “one-drop rule,” or hypodescent, a form of racial classification that served for centuries to determine the minority status of mixed-race people, and arguably continues, in an insidious sort of way, to maintain America’s racial hierarchy. Bearing that and a whole lot of history in mind, I assumed that unsavory characters past and present would consider “East Asian” my “primary” race and “white” my “secondary,” since the minority necessarily eclipses the majority. I wondered idly whether “tertiary race” was an option, too. What about quaternary? Quinary? I put “East Asian” first, thinking that, in a problematic historical context, my mother’s “minority status” solidified mine. Nothingness and “disbelonging” don’t even begin to cover the impact of my limited options.

These feelings of, I would argue, being rendered less-than-human—less-than-white, less than-whole—like so many of our predecessors and contemporaries, are heightened by the fact that there’s actually very little research on the multiracial experience. Most studies out there concern how others perceive multiracial people rather than our actual lived experiences, though it is admittedly difficult to encapsulate the latter when our backgrounds are so diverse. What’s more, even when our backgrounds are technically the same, our experiences may not be; they are often contingent on location, as well as a family’s choice to integrate and educate their children on what cultures comprise them.

Socioeconomic status plays a considerable part as well. As Lauren D. Davenport of Stanford University found, “wealth is tied to perceptions of whiteness and ‘whiter’ identification in [multiracial] individuals,” something I cannot help but suspect is influenced by the history of colonization and exploitative trade practices, including but not limited to chattel slavery (Davenport 62). Research for another day, I think, lest I digress.

I recently asked my brother Matt about his thoughts on our upbringing and our first cousins, who are all half-Filipino, half-white, and middle-class like us. He said he felt that the lack of a Filipino community—which my mom and her siblings grew up with, which our younger cousins in Cleveland grew up with, and our littlest cousin in Western Mass also lack— has contributed to an acute sense of disconnection from our Asian roots. There were simply no Filipinos in our small town, save one family at church whom we saw less than once a week, but the children were much older than us. Cooking Filipino food and learning a few Tagalog words from our grandparents wasn’t enough to make us feel that we were just as much Asian as white —particularly since our town was comprised overwhelmingly of the latter. Our family was just one of three half-Asian, half-white households amidst a population of approximately 25,000. There was us, the Bateses, then the Klines and the Fiskes, all with East Asian mothers (Chinese for the Klines, Korean for the Fiskes) and white fathers. Thanks to my mother’s gregariousness—and, perhaps in unconscious part, her desire to seek company in those who looked more like her—we’ve been close with both families since adolescence, extremely so with the Fiskes. But our mothers hail from vastly different nations, which boast commonalities only on a very broad scale. Such commonalities did, I think, bring us together initially, as did being mistaken for siblings and targeted with racist jokes (a boy in eighth grade only ever called me “Asian,” not Abby, always pulling up the corners of his eyes as he did so), but this did little for the loneliness that a shared culture might have eased.

Something did separate Matt and me from the Kline and Fiske children: our racial ambiguity. Even now, people who don’t know us tend to guess that we’re “mixed” rather than Asian. The fact that we apparently looked neither distinctly Asian nor distinctly white was yet more fuel for identity confusion.

I’d say it still is, since Matt noted that he’s always felt that I’m the one who looks “more Asian.” In contrast to my round face and darker, narrower eyes, my brother’s Eurocentric features, courtesy of our father and augmented by our mother’s coppery coloring, prompt inquiries about Italian or Spanish heritage. I took this to mean that others have consistently made Matt feel “less Asian” than me, though I do recall the strange illogic of childhood arguments about who was “more Asian” than the other. I hate to think that I contributed in any capacity to the advent of his identity confusion, but I can’t ignore what seems very likely, either. Davenport attests that “[multiracials] negotiate their identification based on interpersonal encounters, neighborhoods, and places of worship, classifying themselves in relation to their peers and adopting the label deemed most acceptable in a given context” (58). It’s a little absurd to think that it’s more “acceptable” for me to identify as Asian than my brother. We do, after all, share the same parents and about 50% of the same DNA; but even as children we weren’t immune to the limitations imposed upon us by racial categorization.

For this reason, I believe it’s fair to say that even within multiracial families members can have entirely different outlooks and experiences, especially when we are constantly told by others what we are—or what we seem to be—and what we are not. The way we self-identify varies just as much as the physical expression of our genetics, while our appearances, “alongside biological, cultural, or both biological and cultural information reflecting a mixed-race background” habitually inform how others perceive and label us.

Consider, if you will, the fact that people tend to refer to President Obama as Black even though he’s half-Black, half-white. Would they refer to him as such if he were white-passing? Is it not, moreover, quite accurate to infer that hypodescent still influences racial categorization when its “prominent history in defining racial categories…[held] that the race of a mixed-race child corresponds to that of the ‘socially subordinate’ parent?” (Peery and Bodenhausen 973). Does the past not echo in the act of calling Obama “just” Black, taking into account his “biological and cultural information” and picking the pieces that satisfactorily define him—and his physical appearance—for the public?

In the U.S., social conceptions of race have been historically inflexible, to say nothing of discriminatory, and seem to allow little room for intersectionality beyond the field of academia and social discourse. This, paired with the aforementioned lack of multiracial research, contributes much to the difficulty of understanding our demographic.

Christina Animashaun observes the following, and it is particularly poignant:

Multiracial people have long been targets of fear and confusion, from suspicions of mixed people ‘passing’ as white under the Jim Crow system to accusations of not embracing one’s ‘race’ enough…Research has shown that, even today, monoracial people experience mixed people as more ‘cognitively demanding’ than fellow monoracial people. (Animashaun)

“Cognitively demanding,” indeed, as if multiracial people are a concept and not a reality—as if we are not even people.

In the same vein, being asked, “where are you from?” followed by, “no, where are you really from?” reads like a dehumanizing interrogation, not harmless, friendly curiosity. Such questions tell us that we don’t belong because we look different or are objects of suspicion because we can’t be pigeonholed on sight.

To the casual eye, social categorization seems a tool for navigation and understanding others as they relate to us. Categorization in general makes overwhelming numbers easier to parse; there’s something very fixed and mathematical about it. Yet as an organizational device, it is both simplistic and reductive, bereft of nuance. It has harmful repercussions, reminiscent of physiognomy, a racist pseudoscience that claimed one could understand one’s psychological makeup based on physical appearance.

Perhaps it goes without saying that social categorization leads to bias and discrimination, as the following passage illustrates:

Social categorization differs from other forms of categorization in that people tend to place themselves in a category [11], leading them to be partial to members of their own group (ingroup) relative to those from other groups (outgroup) in terms of social preferences, empathic responding, and resource distribution [12–15]. Beyond sheer partiality and greater liking of members of one’s own group, some of the most invidious effects of social categories result from the biased belief systems that social categorization supports, including stereotypes for, essentialist beliefs about, and even dehumanization of, members of certain social groups. (Liberman et al.)

Yet despite the restrictions so long imposed upon us—or perhaps directly because of them— multiracial people have come to “adopt flexible cognitive and behavioral strategies” and possess “identity flexibility, or the ability to freely and easily switch between or identify with [our] multiple racial identities at a given moment,” something perhaps more commonly known as code-switching (Gaither 115). This is framed as a positive phenomenon, a way to easily navigate and adapt to different social situations, but I’m not certain code-switching to accommodate your environment is conducive to a strong sense of self. I won’t deny its social necessity—particularly as a tool for safety, such as how a person of color in the U.S. might alter their demeanor in the presence of cops—but changing how you act to “seem” more monoracial is fundamentally contrary to being multiracial. I’d wager it could be psychologically detrimental in the long term. Is it any wonder that we are prone to poor psychological health and racial imposter syndrome, that we are so rarely sure of who we are and where we stand? Our existence is lauded for contributing to ever-growing diversity, yet are we people—diverse and dignified, despite obstacles and uncertainty—or a collection of token minorities wielded for political clout and vague narratives about equality? There is talk of “a dream that is the polar opposite of the MAGA fantasy—but a fever dream nonetheless—that a multicultural and mixed-race majority will bring about a post-racial world.” Yet, as Ronald R. Sundstrom of the University of San Francisco reminds us, “demography is not destiny,” and it is unfair to place such expectations on a demographic that is still so little understood, one that does not experience the empathy and representation it merits (Sundstrom).

A Hopeful Resolution to My Little Sob Story

With encouragement from a friend, I contacted Dr. Talusan’s daughter this spring, though I still feared that he was right—that she would deign to like me, but only accept the part of me that would appeal to her own identity. I needn’t have worried, as we established a rapport almost instantly.

Just the same, it has taken me years to grapple with how I self-identify, to finally see myself as someone who can be both Asian and white, someone who doesn’t have to pick sides. It has taken me years to forge a lasting peace between these two seemingly irreconcilable fractions, the two halves of the whole that I am.

And I do know who I am, which is far more important than what I am to others.

Works Cited

Animashaun, Christina. “The Loneliness of Being Mixed Race in America.” Vox, 18 Jan. 2021, https://www.vox.com/platform/amp/first-person/21734156/kamala-harris-mixed-race biracial-multiracial.

Davenport, Lauren D. “The Role of Gender, Class, and Religion in Biracial Americans’ Racial Labeling Decisions.” American Sociological Review, vol. 81, no. 1, 2016, pp. 57–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24756399. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Gaither, Sarah E. “‘Mixed’ Results: Multiracial Research and Identity Explorations.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, vol. 24, no. 2, 2015, pp. 114–19. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44318839. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Liberman, Zoe, et al. “The Origins of Social Categorization.” Trends in cognitive sciences vol. 21,7 (2017): 556-568. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2017.04.004.

Nadal, Kevin L., et al. “Microaggressions Within Families: Experiences of Multiracial People.” Family Relations, vol. 62, no. 1, 2013, pp. 190–201. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23326035. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Parker, Kim, et al. “Multiracial in America: Proud, Diverse, and Growing in Numbers.” Pew Research Center, 11 June 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/06/11/ multiracial-in-america/.

Peery, Destiny, and Galen V. Bodenhausen. “Black + White = Black: Hypodescent in Reflexive Categorization of Racially Ambiguous Faces.” Psychological Science, vol. 19, no. 10, 2008, pp. 973–77. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40064830. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022.

Salhany, Anna. “Racial Imposter Syndrome Makes You Feel Like Your Identity Isn’t Yours.” Vice, 3 March 2022, https://www.vice.com/en/article/93bn7e/what-is-racial-imposter syndrome.

Sundstrom, Ronald R. “Kamala Harris, Multiracial Identity, and the Fantasy of a Post-Racial America.” Vox, 20 Jan. 2021, https://www.vox.com/first-person/22230854/kamala harris-inauguration-mixed-race-biracial.

Wong, Kristin. “The Biracial Bind of Not Being Asian Enough.” Refinery29, 17 May 2019, https://www.refinery29.com/amp/en-us/2019/05/232641/half-asian-biracial-personal essay.

About the Author

Abby Bates is a recent University Without Walls graduate and writer. Queer and multiracial, her nonfiction works typically combine academic research with personal experience, reflection, and humor.