Unit V: Historical and Contemporary Feminist Social Movements

Third Wave and Queer Feminist Movements

“We are living in a world for which old forms of activism are not enough and today’s activism is about creating coalitions between communities.”

—Angela Davis, cited by Hernandez and Rehman in Colonize This!

Third wave feminism is, in many ways, a hybrid creature. It is influenced by second wave feminism, Black feminisms, transnational feminisms, Global South feminisms, and queer feminism. This hybridity of third wave activism comes directly out of the experiences of feminists in the late 20th and early 21st centuries who have grown up in a world that supposedly does not need social movements because “equal rights” for racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women have been guaranteed by law in most countries. The gap between law and reality—between the abstract proclamations of states and concrete lived experience—however, reveals the necessity of both old and new forms of activism. In a country where white women are paid only 75.3% of what white men are paid for the same labor (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2016), where police violence in black communities occurs at much higher rates than in other communities, where 58% of transgender people surveyed experienced mistreatment from police officers in the past year (James et. al 2016), where 40% of homeless youth organizations’ clientele are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (Durso and Gates 2012), where people of color—on average—make less income and have considerably lower amounts of wealth than white people, and where the military is the most funded institution by the government, feminists have increasingly realized that a coalitional politics that organizes with other groups based on their shared (but differing) experiences of oppression, rather than their specific identity, is absolutely necessary. Thus, Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake (1997) argue that a crucial goal for the third wave is “the development of modes of thinking that can come to terms with the multiple, constantly shifting bases of oppression in relation to the multiple, interpenetrating axes of identity, and the creation of a coalitional politics based on these understandings” (Heywood and Drake 1997: 3).

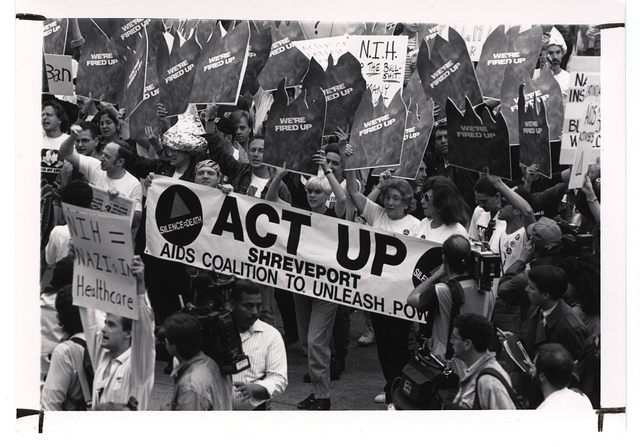

In the 1980s and 1990s, third wave feminists took up activism in a number of forms. Beginning in the mid 1980s, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) began organizing to press an unwilling US government and medical establishment to develop affordable drugs for people with HIV/AIDS. In the latter part of the 1980s, a more radical subset of individuals began to articulate a queer politics, explicitly reclaiming a derogatory term often used against gay men and lesbians, and distancing themselves from the gay and lesbian rights movement, which they felt mainly reflected the interests of white, middle-class gay men and lesbians. As discussed at the beginning of this text, queer also described anti-categorical sexualities. The queer turn sought to develop more radical political perspectives and more inclusive sexual cultures and communities, which aimed to welcome and support transgender and gender non-conforming people and people of color. This was motivated by an intersectional critique of the existing hierarchies within sexual liberation movements, which marginalized individuals within already sexually marginalized groups. In this vein, Lisa Duggan (2002) coined the term homonormativity, which describes the normalization and depoliticization of gay men and lesbians through their assimilation into capitalist economic systems and domesticity—individuals who were previously constructed as “other.” These individuals thus gained entrance into social life at the expense and continued marginalization of queers who were non-white, disabled, trans, single or non-monogamous, middle-class, or non-western. Critiques of homonormativity were also critiques of gay identity politics, which left out concerns of many gay individuals who were marginalized within gay groups. Akin to homonormativity, Jasbir Puar coined the term homonationalism, which describes the white nationalism taken up by queers, which sustains racist and xenophobic discourses by constructing immigrants, especially Muslims, as homophobic (Puar 2007). Identity politics refers to organizing politically around the experiences and needs of people who share a particular identity. The move from political association with others who share a particular identity to political association with those who have differing identities, but share similar, but differing experiences of oppression (coalitional politics), can be said to be a defining characteristic of the third wave.

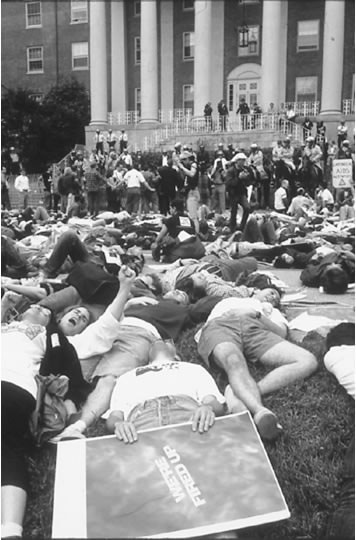

Another defining characteristic of the third wave is the development of new tactics to politicize feminist issues and demands. For instance, ACT UP began to use powerful street theater that brought the death and suffering of people with HIV/AIDS to the streets and to the politicians and pharmaceutical companies that did not seem to care that thousands and thousands of people were dying. They staged die-ins , inflated massive condoms, and occupied politicians’ and pharmaceutical executives’ offices. Their confrontational tactics would be emulated and picked up by anti-globalization activists and the radical Left throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. Queer Nation was formed in 1990 by ACT UP activists, and used the tactics developed by ACT UP in order to challenge homophobic violence and heterosexism in mainstream US society.

Around the same time as ACT UP was beginning to organize in the mid-1980s, sex-positive feminism came into currency among feminist activists and theorists. Amidst what is known now as the “Feminist Sex Wars” of the 1980s, sex-positive feminists argued that sexual liberation, within a sex-positive culture that values consent between partners, would liberate not only women, but also men. Drawing from a social constructionist perspective, sex-positive feminists such as cultural anthropologist Gayle Rubin (1984) argued that no sexual act has an inherent meaning, and that not all sex, or all representations of sex, were inherently degrading to women. In fact, they argued, sexual politics and sexual liberation are key sites of struggle for white women, women of color, gay men, lesbians, queers, and transgender people—groups of people who have historically been stigmatized for their sexual identities or sexual practices. Therefore, a key aspect of queer and feminist subcultures is to create sex-positive spaces and communities that not only valorize sexualities that are often stigmatized in the broader culture, but also place sexual consent at the center of sex-positive spaces and communities. Part of this project of creating sex-positive, feminist and queer spaces is creating media messaging that attempts to both consolidate feminist communities and create knowledge from and for oppressed groups.

In a media-savvy generation, it is not surprising that cultural production is a main avenue of activism taken by contemporary activists. Although some commentators have deemed the third wave to be “post-feminist” or “not feminist” because it often does not utilize the activist forms (e.g., marches, vigils, and policy change) of the second wave movement (Sommers, 1994), the creation of alternative forms of culture in the face of a massive corporate media industry can be understood as quite political. For example, the Riot Grrrl movement, based in the Pacific Northwest of the US in the early 1990s, consisted of do-it-yourself bands predominantly composed of women, the creation of independent record labels, feminist ‘zines, and art. Their lyrics often addressed gendered sexual violence, sexual liberationism, heteronormativity, gender normativity, police brutality, and war. Feminist news websites and magazines have also become important sources of feminist analysis on current events and issues. Magazines such as Bitch and Ms., as well as online blog collectives such as Feministing and the Feminist Wire function as alternative sources of feminist knowledge production. If we consider the creation of lives on our own terms and the struggle for autonomy as fundamental feminist acts of resistance, then creating alternative culture on our own terms should be considered a feminist act of resistance as well.

As we have mentioned earlier, feminist activism and theorizing by people outside the US context has broadened the feminist frameworks for analysis and action. In a world characterized by global capitalism, transnational immigration, and a history of colonialism that has still has effects today, transnational feminism is a body of theory and activism that highlights the connections between sexism, racism, classism, and imperialism. In “Under Western Eyes,” an article by transnational feminist theorist Chandra Talpade Mohanty (1991), Mohanty critiques the way in which much feminist activism and theory has been created from a white, North American standpoint that has often exoticized “3rd world” women or ignored the needs and political situations of women in the Global South. Transnational feminists argue that Western feminist projects to “save” women in another region do not actually liberate these women, since this approach constructs the women as passive victims devoid of agency to save themselves. These “saving” projects are especially problematic when they are accompanied by Western military intervention. For instance, in the war on Afghanistan, begun shortly after 9/11 in 2001, U.S. military leaders and George Bush often claimed to be waging the war to “save” Afghani women from their patriarchal and domineering men. This crucially ignores the role of the West—and the US in particular—in supporting Islamic fundamentalist regimes in the 1980s. Furthermore, it positions women in Afghanistan as passive victims in need of Western intervention—in a way strikingly similar to the victimizing rhetoric often used to talk about “victims” of gendered violence (discussed in an earlier section). Therefore, transnational feminists challenge the notion—held by many feminists in the West—that any area of the world is inherently more patriarchal or sexist than the West because of its culture or religion through arguing that we need to understand how Western imperialism, global capitalism, militarism, sexism, and racism have created conditions of inequality for women around the world.

In conclusion, third wave feminism is a vibrant mix of differing activist and theoretical traditions. Third wave feminism’s insistence on grappling with multiple points-of-view, as well as its persistent refusal to be pinned down as representing just one group of people or one perspective, may be its greatest strong point. Similar to how queer activists and theorists have insisted that “queer” is and should be open-ended and never set to mean one thing, third wave feminism’s complexity, nuance, and adaptability become assets in a world marked by rapidly shifting political situations. The third wave’s insistence on coalitional politics as an alternative to identity-based politics is a crucial project in a world that is marked by fluid, multiple, overlapping inequalities.

In conclusion, this unit has developed a relational analysis of feminist social movements, from the first wave to the third wave, while understanding the limitations of categorizing resistance efforts within an oversimplified framework of three distinct “waves.” With such a relational lens, we are better situated to understand how the tactics and activities of one social movement can influence others. This lens also facilitates an understanding of how racialized, gendered, and classed exclusions and privileges lead to the splintering of social movements and social movement organizations. This type of intersectional analysis is at the heart not only of feminist activism but of feminist scholarship. The vibrancy and longevity of feminist movements might even be attributed to this intersectional reflexivity—or, the critique of race, class, and gender dynamics in feminist movements. The emphasis on coalitional politics and making connections between several movements is another crucial contribution of feminist activism and scholarship. In the 21st century, feminist movements confront an array of structures of power: global capitalism, the prison system, war, racism, ableism, heterosexism, and transphobia, among others. What kind of world do we wish to create and live in? What alliances and coalitions will be necessary to challenge these structures of power? How do feminists, queers, people of color, trans people, disabled people, and working-class people go about challenging these structures of power? These are among some of the questions that feminist activists are grappling with now, and their actions point toward a deepening commitment to an intersectional politics of social justice and praxis.