CompLit 293 Gender and Global Literature

Olivia Davis

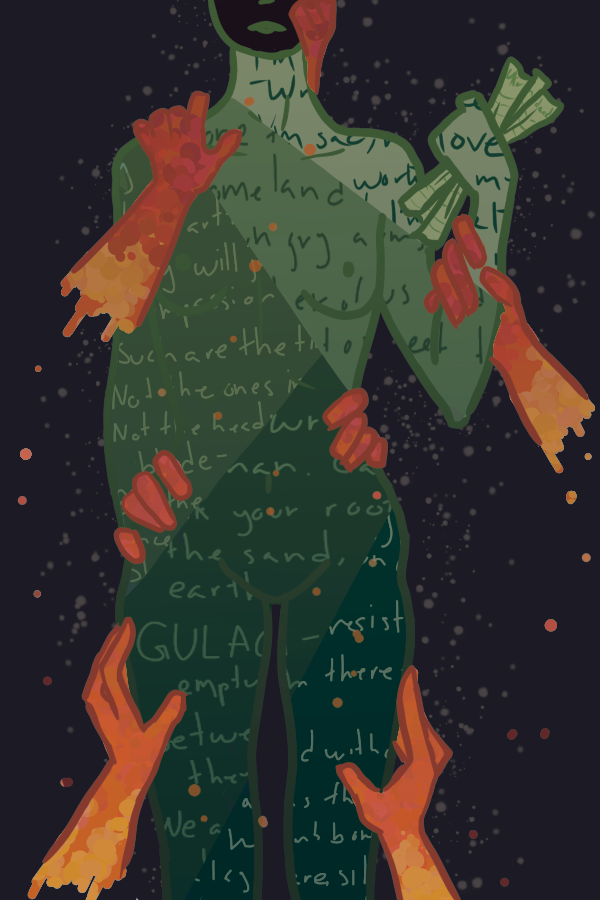

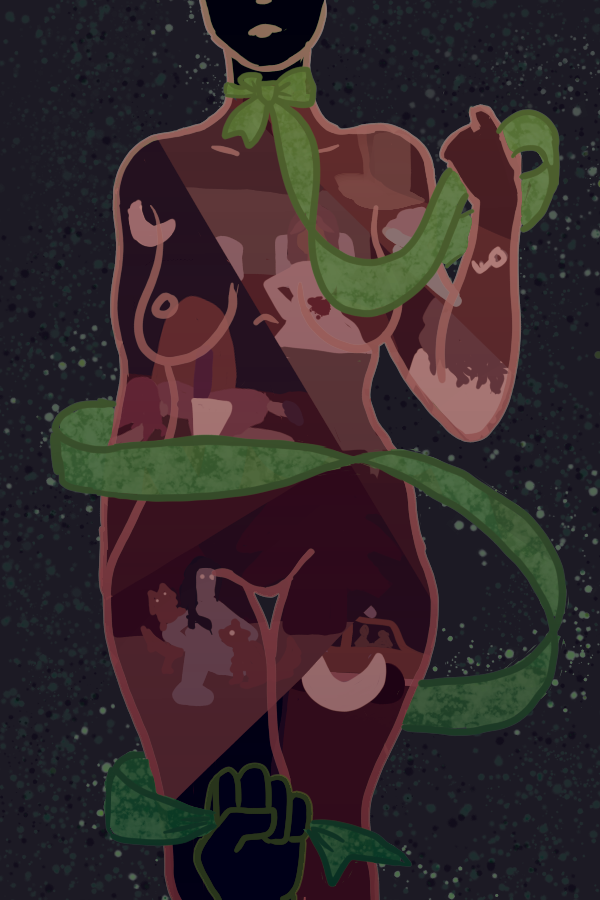

This piece, a two-work set of two digital paintings, compares Carmen Maria Macahdo’s “The Husband Stitch” and Oksana Zabuzhko’s Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex and their depictions of the patraiarchal system. “The Husband Stitch” is a world of magical realism that explores the patriarchy through the retelling of various urban legends, wrapped up in the narrator’s green ribbon which she refuses to let her husband touch. Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sexfollows a protagonist who struggles with her Ukrainian nationality and her womanhood, exploring the intersection between various identities and the forms of violence that come with them. Both “The Husband Stitch” and Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex have a dual mode of understanding and processing the effects of patriarchal systems on women: the first method is an exploration of how external factors cause physical and embodied harm, and the second is a storytelling aspect that both reveals the harmful impacts of these systems as well as acting as a way of reclaiming or processing that pain.

The depiction of “The Husband Stitch,” represents the external factors of the patriarchy through the use of the ribbon, as is also done in the story itself. The ribbon acts throughout the story as a boundary that the husband continually wishes to cross, despite repeated refusals, and one that, in the end, kills the narrator. Though there are other violations, such as the jokes about sewing her tighter after childbirth—“How much to get that extra stitch?” (17)—and the like, the ribbons are systemic and physical, as shown both by the fact that all women have them, and that their removal causes harm. This systemic nature is somewhat directly commented on in the lines, “I am up for a long time listening to his breathing, wondering if perhaps men have ribbons that do not look like ribbons. Maybe we are all marked in some way, even if it’s impossible to see” (21). Given the dynamics of the story, the ribbon is represented as being undone by a clenched, masculine fist at the bottom, a slow pull that will undo her. The woman is holding the ribbon loosely, depicting her repeated refusals that eventually are worn down to consent; it is an effort to stop the harm, but it is not effective in the end.

In this piece, the woman’s body is subdivided into the urban legends that are scattered throughout the story. Each story represents a different fear of womanhood, as mentioned on page 11: “Brides never fare well in stories. Stories can sense happiness and snuff it out like a candle.” In these stories, the women tend to meet unhappy ends, and yet these stories are also the ones that are told (or retold) to us by the narrator, not something done to her. This seems to be done as a way of processing or understanding the unfair pain of the world, as she says at the end of the killer’s story at the end of the work “I’m sorry. I’ve forgotten the rest of the story” (30). Though this “forgetting” may not be part of the legend she is telling, it is indicative of their role in the story: these legends are all being filtered through her and are retold, used to help her process. As such, the stories are inscribed on her body in my artwork, the result of what the narrator chooses to tell us. They are the result of trauma, but are being reclaimed and shown to us.

The depiction of Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex shows the dual nature of the patriarchy. One of the most major ways the external pain is shown is through sex. In many ways, women become objectified and used for sex in this story, as even on page 7 it asks “is there nothing other than my sex organs that interest you?” There is the continual mention of sexual assault and sexual violence, with her husband and by the man on the train on page 86, and this is shown with the disembodied hands, as it is not just the specific men that assault, but also the faceless cultural sexual assault. This cultural nature of the sexual assault is brilliantly described like this: “What can I tell you[…]? […]That we were raised by men fucked from all ends every which way? That later we ourselves screwed the same kind of guys, and that in both cases they were doing to us what others, the others, had done to them?” (158). This is why in her hand is clutched a piece of paper with “Ukraine is not yet dead” written on it, as it is a refrain in the story that shows the pain and struggle of Ukraine to continue, even painfully. The other form, poetry, is very symbolically similar to the use of urban legends in “The Husband Stitch” in that it remixes and reforms and retells trauma as a form of processing and understanding it. The poems selected are those from pages 40, 49, 50, 60, and 78 from top to bottom.

These pieces do not simply draw inspiration from the two works, but also from ideas of Audrey Lorde. Her representation of her past in Zami as a biomythography served as a base of understanding, especially the idea of rewriting history as a form of catharsis or re-understanding. Additionally, “Poetry is not a Luxury,” also by Audre Lorde, drew further connections between the two pieces. One influential quote comes from the first few lines:

The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are—until the poem—nameless and formless, about to be birthed, but already felt.

It is through this, and the mention by Zabuzhko of women in Ukraine finally feeling seen, that the pieces truly became clear. Poetry, here the legends and poems both, as well as the stories as a whole, are methods of naming. Not only are they naming for one’s own self, but also for others to see and understand. That is why the poems and legends had to be visibly shown on the body in my piece: it shows the embodiment of the problems, the personal nature of telling and retelling, and showing the very person as a vehicle for their messages and ideas—their naming of the world and its problems. It is through this naming and re-understanding of the world that it can be changed, and it through change that the world can become a better version of itself.

Works Cited

“The Husband Stitch.” Her Body and Other Parties, by Carmen Maria Machado, Serpent’sTail, 2019.

Lorde, Audre. Poetry Is Not a Luxury. Druck- & Verlagscooperative, 1993.

Zabužko Oksana, and Halyna Hryn. Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex. Amazon Crossing, 2011, Kindle.