INTRODUCTION

Writing as Conversation: Cultivating a Rhetorical Mindset

It’s hard to imagine living in the world and not being a reader and writer of texts. Our culture is saturated with words and images. We may write emails and text messages to family and friends, compose essays for college coursework, fill out job applications, post consumer reviews, voice our concerns about issues in public forums, and so on. We are called upon to write for personal, academic, professional, and civic purposes. Quite simply, writing is fundamental to our everyday lives.

In fact, in The Rise of Writing: Redefining Mass Literacy, literacy researcher Deborah Brandt argues that we are encountering a distinct moment in history when writing is becoming more common, more pervasive, and more integral to the mass public. College students have contributed to this groundswell in writing. Researcher Andrea Lunsford has provided ample evidence for writing activity in her five-year study of 1,616 undergraduates and the approximately 15,000 pieces of writing they produced during that period. Interviewed for Wired Magazine, Lunsford contends, “I think we’re in the midst of a literacy revolution the likes of which we haven’t seen since Greek civilization” (qtd. in Thompson). Those who lament the decline of writing in society misunderstand this moment. “For Lunsford,” Wired writer Clive Thompson explains, “technology isn’t killing our ability to write. It’s reviving it–and pushing our literacy in bold new directions.”

Digital media have created opportunities for a greater volume of published texts (including this one!), more rapid speed in their circulation, and potentially, more extensive reach to readers in our own communities and across the globe. In the 1990s, as the internet became publicly available and we became more attuned to globalization, there was a widespread belief that technology and globalization had a democratizing effect: everyone can write and circulate their writing, everyone can be read, everyone will have a voice in our world. But the past two decades have called these ideals into question. Even in digital and global contexts, inequalities persist through uneven access to digital technologies and writing education, the prevalence of the English language and a related anxiety (even intolerance) about language diversity in the United States, and serious problems of power and privilege that enable some to be heard more than others. Many of us do have more opportunities to write and circulate our writing; however, the “literacy revolution” turned out to be more complicated than we had hoped.

One way to understand these issues is by continually reflecting on how we each fit into this historical moment. How might you narrate your own reading and writing histories? What have reading and writing meant to you? What kinds of writing have you valued? Who or what supported or hampered you in your writing life? Your first assignment for this class will ask you to do just this kind of reflection. In the Initial Writer’s statement you will consider your own writing history and use it as a starting place for the work you will do this semester. Additionally, the five opening essays of Unit 1 also reflect on writing in this way (and others). You might review these to consider which one speaks most directly to your experiences.

The fact that texts can travel faster and farther than ever raises complex questions about communicating across borders and with diverse peoples. Writers learn about and draw from multiple cultures, language and writing traditions, and technologies. Writers and readers may not share the same cultural heritage, political beliefs, or economic privilege and constraints. And as a result, we may have different expectations about what constitutes good writing. The issue isn’t only that we are writing more these days. Rather, writing itself has become an increasingly complicated cognitive and social activity.

So what does it mean to write well in this brave new world? Learning to write well means learning how to effectively engage in a conversation in the context of cultural, social, economic, and political differences. Consider this well-worn metaphor for writing:

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally’s assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress. (Burke 110-111)

If the idea of a “parlor” seems quaint today, we can replace the parlor with a living room, a coffee shop, a blogging community, a political organization. The idea of conversation, however, is timeless and fundamental to writing. What conversations do we want to join, and why? As we compose our texts, how do we each draw on our writing traditions, language backgrounds, sociocultural contexts, and technological resources? And how do we engage with others who may not share our beliefs and worldviews?

Opening Conversations is a collection of essays that all embody the spirit of writing as conversation; a committee of college writing instructors at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Writing Program designed this collection for writers, specifically those in college writing courses. On the one hand, there is certainly diversity here. These essays explore contemporary social issues–including language, immigration, technology, health care, sport, and more–and are wide-ranging in writerly perspective, essay form and style, and publication context. The editors made a decision to include essays that speak across differences–including but not limited to race, gender, sexuality, class, and language background–because these essays demonstrate the ways in which different writers compose texts to readers who may not share the same worldview. With this collection, we recognize that the essay as a genre is versatile and malleable, far from uniform.

At the same time, we’d like to emphasize what these essays share: all of these essays illustrate the ways in which writers can step into the parlor and join a conversation. While the parlor metaphor quoted above may imply oppositional conversations (note terms above: “defense,” “ally,” and “opponent”), this collection suggests purposes for writing that include but also go beyond argument:

- writers who critically reflect on how their contexts have influenced their worldviews;

- writers who respond to other writers–not simply to fall into facile agree-disagree arguments, but rather to engage in true dialogue;

- writers who are open to discovery, who rethink an existing worldview;

- writers who research and synthesize multiple sources to understand a conversation;

- writers who add to the conversation, whose texts do something in the world.

Readers will find different ways of cataloguing writerly purpose in these pages. For now, we cast writing as conversation in order to highlight that writing is about social engagement. It’s important to remind ourselves that texts are integral to our social lives, and writing can act in meaningful ways to help us build relationships with others and create change in our communities. In short, writing can have an impact on our worlds. And for this reason, writing can be powerful. As you read this collection, we urge you to read as writers: contemplate the choices that these writers have made to join and even re-imagine conversations. If writing is about acting on our worlds, then learning to write well requires learning to cultivate a rhetorical mindset.

The Rhetorical Situation

Rhetoric is the art of using symbolic resources (e.g., words, languages, genres, images) in order to communicate effectively within a particular social context. Cultivating a rhetorical mindset means carefully examining the ways in which writers and speakers make decisions about symbolic resources according to one’s purpose, audience, and contexts. When we communicate in writing and speech, many of us already adapt what we say and how we say it to a given audience. But cultivating a rhetorical mindset entails more intentional contemplation about how to develop a set of rhetorical strategies and habits of mind that will help us write deftly and powerfully for diverse and shifting contexts. In what follows, we present a few rhetorical concepts to get started.

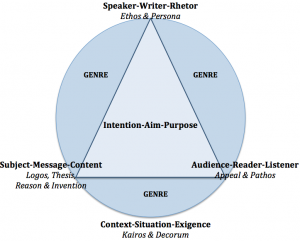

All writing is situated. Often represented as a rhetorical triangle, the rhetorical situation can help us understand the essential elements of a communicative situation:

Reproduced from: Essentials for ENGL-121 Copyright © 2016 by David Buck is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

In short, a writer composes a text about a topic to readers. But why?

Rhetorician Lloyd Bitzer explains that “rhetorical discourse comes into existence as a response to a situation, in the same sense that an answer comes into existence in response to a question, or a solution in response to a problem” (5). Writers compose texts in response to an exigence, a perceived need or desire that calls for a response. Put another way, we are often motivated to write when we care enough about the issue and when we believe that our writing can do something to address that question or problem. Exigences arise from our experiences in the world and can move us to write about these issues: e.g., proposed legislation, a cultural event (e.g. football game, a lecture), an injustice, a blog about a social issue, etc. Exigences are invitations to write.

Writers in a particular rhetorical situation must determine their purpose and identify the most suitable audience. Who needs to read this text? What can readers do to address the question or remedy the problem? It makes sense to tailor our texts to readers who can help address the exigence–perhaps by changing their mindset or taking action in the world. In addition to identifying an appropriate audience, we need to make decisions about how to compose a text by drawing on symbolic resources, including writing traditions, languages, and rhetorical strategies. We consider options for content, form, style, language, and media, and we then compose, revise, and edit a text tailored to the intended readers.

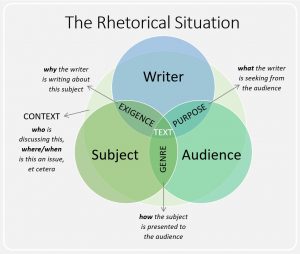

The rhetorical triangle provides a useful start: the basic parts of a rhetorical situation are exigence, writer, reader, topic, and text. But as a static visual, the rhetorical triangle may be deceptively simple. First, the image may not adequately emphasize relationships among the parts of the rhetorical situation. What is the relationship between writer and topic, reader and topic, writer and reader? How do these relationships impact how we should compose a text? Second, a rhetorical situation is only a snapshot within an ongoing conversation; looking only at the situation, we might not see how the situation and its elements are part of wider social and historical contexts. That is, how is a given rhetorical situation part of an ongoing conversation? How has a particular topic been discussed in the past, and who was involved? What beliefs, past experiences, knowledge, and identities do writers bring to the situation? What do readers bring to the situation?

See here for one representation of this situation:

Reproduced from: Essentials for ENGL-121 Copyright © 2016 by David Buck is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The concept of a rhetorical situation provides writers with a beginning. The next step is to examine how an interplay of contexts can affect a rhetorical situation.

A Writer’s Contexts

All writers are shaped by our contexts. To each rhetorical situation, we bring our life experiences, our knowledge, and our identities and beliefs. Good writers, we propose, are thoughtful about how our contexts have shaped our sense of self and the perspective that we bring to what, how, and why we write. For this reason, we might ask ourselves, What social contexts am I a part of? How have these contexts shaped my outlook on the world? These are admittedly big questions. As the essays in this collection suggest, contexts may include places, social groups, complex social identities or economic and political systems. Writers carry the experiences and assumptions from these contexts into writing situations and so it’s worth critically reflecting on where we’ve come from.

This idea of a writer’s contexts may feel abstract but the idea starts to become clearer when we look at the particulars of writers’ texts. Several writers in this collection engage in critical self-reflection to varying degrees. Further, all writers must decide on how to represent themselves. The rhetorical concept of ethos, or an appeal to the credibility or character of the writer or speaker, is instructive here. How do writers decide to represent themselves through content and style? What does each reveal about him/herself, and why? What does each withhold? How would we describe his/her character, and how does this fit with the writer’s purpose in the text? What message are they sending about their character? Even when writers are not narrating personal experience, ethos is always present. We imply our credibility and character through our writing choices. In responding to a text, readers will form an understanding of a writer’s character and determine whether the writer is ethical, credible, trustworthy. In a sense, when we reflect on our own contexts, we are also reflecting on our relationship to others in the parlor.

Listening to Others: Critical Inquiry & Response

The parlor metaphor points to the fact that we are always in the company of others–others who bring their own contexts. As much as we should listen to our own experiences, it’s equally important to listen, truly listen to others in the parlor. Reading and writing (listening and speaking, too) depend on one another. As the parlor metaphor indicates, “others have long preceded” us in the conversation. Before we add our voices, we ought to listen in to understand what others say and also to identify who is part of the conversation and how others bring their contexts to bear on the conversation. Such listening is not always easy: a text may be difficult and complex, the topic may be unfamiliar, we may not connect with a given writer’s experiences, and we may even be offended by a writer’s worldview. Some voices in the parlor are going to be louder than others, some silenced. Despite these difficulties, listening carefully and respectfully is important: it is not only ethical, but also this act helps writers comprehend the contours of a conversation and to begin to respond to that conversation. In practical terms, listening well can be cued by fair and accurate summary, paraphrase, and quoting of others in the conversation.

It’s not surprising that writers in academic communities and beyond will often write in response to a text. Listening to others–or in this case, reading texts by others–can also be generative. If we approach a text with an open mind, with an attempt to understand others, we can also engage in critical inquiry: analyzing aspects of the text, making connections between different claims, extending the ideas presented, complicating an idea with our prior knowledge and experiences, and more. In short, one’s interaction with a text can lead to new meaning making. As writers, we may even feel compelled to respond where the point of responding isn’t simply to arrive at a yes-no or agree-disagree position. Rather, the best responses will help us more fully understand the nuances of a conversation or even re-imagine the conversation altogether. The best responses open up rather than close down conversations..

Entering a Conversation: What Can Writing Do?

In the end, as writers, we must repeatedly ask ourselves, What conversations do I want to join? If exigence is an invitation to write, where do I find those motivations?What is my exigence, and what do I want my writing to do? What impact do I want my writing to make? We can often find exigences all around us in the texts, events, and relationships that make up our everyday world.

For writers, preliminary and then more careful research offer a way to become familiar with a conversation and identify the stakeholders in that conversation. For those of us who have access to university libraries, we are fortunate to be able to search among huge volumes of sources, including peer-reviewed ones (i.e., sources that have been reviewed and selected for publication by researchers in the discipline). There’s a widespread misconception that research is a passive activity (we let existing library research wash over us) and writing about research can be boring (we then pour this information on readers). Instead, we might see research as a kind of investigative listening: finding, evaluating, responding to, synthesizing, and using a variety of sources. Moreover, weaving multiple perspectives together becomes a kind of invention, a way of making meaning and generating new, compelling lines of inquiry.

Research is not only for academics. Indeed, research is important for many writers–including, for example, news journalists, creative nonfiction writers, cultural critics, activist writers, and sports writers. Moreover, even for academics, research does not only happen in university libraries and through online search engines. If research is about listening and seeking multiple perspectives and sources of information, then research also may also include field observations, interviews with those who affect or are affected by the topic, surveys, and other methods of gathering knowledge and perspectives from our everyday lives.

Research and writing are often recursive and generative processes. As we attempt to analyze, synthesize, and respond to sources, we may discover new lines of inquiry, new exigences, new audiences to reach. We may understand a conversation differently, change our minds, identify new questions. These processes can help us crystallize the most pressing exigence and our purpose in writing. In other words, research is not the end. Research and writing are the means to a goal.

When we write to enter a conversation, the goal is not simply parroting what we’ve learned. Rather, we use research for a purpose–e.g., to invite empathy, to create change in our society, to argue for a particular position. Kairos is a useful rhetorical concept here: Why is this an opportune moment to add one’s voice to a conversation? Our purpose in writing can become a guide as we make decisions about how to make our texts do something in the world: Who needs to read this text at this moment? What genre, medium, and style makes sense in light of purpose and intended readers? What publications would reach these intended readers? How can the text circulate?

Writing, after all, is meant to engage others and create an impact on our worlds. And all texts have power–including those you create! Through their essays, the writers in this collection–and indeed, the writers in your class–affect the ways in which many of us see the world and act in the world.

We Are All Writers

Our hope is that this book opens up conversations about writing and helps you on your own writing journey. In this collection, there are many types of writers. They use humor, passion, measured distance, emotion, contemplation and draw on personal experiences, current events, primary and secondary sources. They include visual images, multiple dialects and languages, genres within genres, and various points of view. As you read these essays and continue to cultivate a rhetorical mindset, we invite you

- to reread this introduction alongside the essays,

- to analyze each writer’s choices in relation to the writer’s publication contexts described in the brief prefaces to each essay.

That is, take note of each writer’s choices, and build a repository of rhetorical strategies to employ in your own writing. But it’s not enough to cultivate a rhetorical mindset and critically reflect on others’ choices. It’s only through practice that you will develop fluency and rhetorical flexibility as well as an ability to add your voice to conversations that matter. So yes, cultivate a rhetorical mindset, but remember also to write–and to write often and with purpose.

Additional Resources for College Writing

The Writing Program has also created two collections of student work for you to use in College Writing:

- The Student Writing Anthology: An Open access collection of work from students in College Writing.

- In Conversation: Student Voices Across Modalities: An open access collection of work from UMass writers in College Writing and Junior Year Writing courses.

Additionally, we recommend the following open access writing resources:

- Tips and Tools from the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill: writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/

- Excelsior Online Writing Lab

- Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing: writingspaces.org/essays/.

Works Cited

Bitzer, Lloyd. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 1.1 (1968): 1-14.

Brandt, Deborah. The Rise of Writing: Redefining Mass Literacy. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2015.

Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1967.

Thompson, Clive. “On the New Literacy.” Wired Magazine, August 24, 2009. http://archive.wired.com/techbiz/people/magazine/17-09/st_thompson