22 Suicide and Prevention

Suicide and Prevention

Suicide prevention sign on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, California.

Suicide is a major public health issue around the world that accounts for almost 800,000 deaths globally per year. In the United States suicide is the 10th leading cause of death with approximately 47,000 total deaths in 2017 and 1.4 million suicide attempts in that same year. While suicidologists and public health officials are understandably preoccupied with suicide deaths and suicide attempts, researchers Jobes and Joiner (2019) have recently reflected on the massive population of people who experience suicidal ideation (thoughts of ending one’s life) and all too often escape the attention of our suicide prevention research, clinical treatments, and even national health care policies. In the United States, 10,600,000 American adults experience serious suicidal thoughts—a worrisome cohort which dwarfs the populations of those who attempt and die by suicide.

The World Health Organization ranks both major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD) among the top 10 leading causes of disability worldwide. Further, MDD and BD carry a relatively high risk of suicide. Individuals with a depressive disorder have a 17-fold increased risk for suicide over the age- and sex-adjusted general population rate. It is estimated that 25%–50% of people diagnosed with BD will attempt suicide at least once in their lifetimes (Goodwin & Jamison, 2007) and 5-6% of individuals with bipolar disorder die by suicide. Furthermore, bipolar disorder may account for one-quarter of all suicide deaths (APA, 2013).

For some people with mood disorders, the extreme emotional pain they experience becomes unendurable. Overwhelmed by hopelessness, devastated by incapacitating feelings of worthlessness, and burdened with the inability to adequately cope with such feelings, they may consider suicide to be a reasonable way out. Suicide, defined by the CDC as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as the result of the behavior” (CDC, 2013a), in a sense represents an outcome of several things going wrong all at the same time (Crosby, Ortega, & Melanson, 2011). Not only must the person be biologically or psychologically vulnerable, but they must also have the means to perform the suicidal act, and they must lack the necessary protective factors (e.g., social support from friends and family, religion, coping skills, and problem-solving skills) that provide comfort and enable one to cope during times of crisis or great psychological pain (Berman, 2009).

Suicide is not listed as a disorder in the DSM-5; however, suffering from a mental disorder—especially a mood disorder—poses the greatest risk for suicide. Around 90% of those who die by suicide have a diagnosis of at least one mental disorder, with mood disorders being the most frequent (Fleischman, Bertolote, Belfer, & Beautrais, 2005). In fact, the association between major depressive disorder and suicide is so strong that one of the criteria for the disorder is thoughts of suicide, as discussed in the previous sections (APA, 2013).

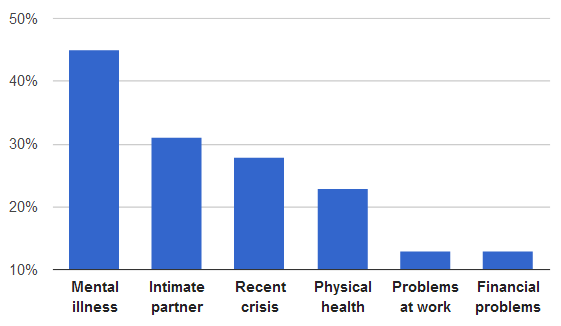

The precipitating circumstances for suicide from 16 American states in 2008

Risk factors

In addition to mental illness, there are several other identified risk factors for suicide. While women are more likely to attempt suicide than men, rates of suicide deaths are generally higher among men than women, ranging from 1.5 times as much in the developing world to 3.5 times in the developed world. Suicide is generally most common among those over the age of 70; however, in certain countries, those aged between 15 and 30 are at the highest risk. Rates of suicide deaths vary across region and country, however the majority of suicide deaths worldwide occur in low- and middle-income countries (World Health Organization). In the US, suicide rates are highest among White and Native American men and lowest among Asian/Pacific Islander and Black women, however suicide affects all racial and ethnic groups. Sexual and gender minority individuals are also at heightened risk of suicide (McKay et al., 2019).

Socio-economic problems such as unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and discrimination may trigger suicidal thoughts. Suicide might be rarer in societies with high social cohesion and moral objections against suicide. War veterans have a higher risk of suicide due in part to higher rates of mental illness, such as post traumatic stress disorder, and physical health problems related to war.

A number of psychological factors can also increase the risk of suicide including: hopelessness, loss of pleasure in life, depression, anxiousness, agitation, rigid thinking, rumination, and poor coping skills. A poor ability to solve problems, the loss of abilities one used to have, and poor impulse control also play a role. In older adults, the perception of being a burden to others is important. Recent life stresses, such as a loss of a family member or friend or the loss of a job, might be a contributing factor. Additionally, certain personality factors, especially high levels of neuroticism and introvertedness, have been associated with suicide. This might lead to people who are isolated and sensitive to distress to be more likely to attempt suicide. On the other hand, optimism has been shown to have a protective effect. Other psychological risk factors include having few reasons for living and feeling trapped in a stressful situation. Changes to the stress response system in the brain might be altered during suicidal states.

Finally, having access to means to take one’s life is a risk factor. For example, suicide rates have been found to be greater in households with firearms than those without them.

Prevention

Perhaps one of the most important developments over the past 20 years in clinical suicidology has been the development and use of different versions of suicide-focused interventions that focus on stabilization planning for prospective acute suicidal crises. In marked contrast to the coercive and unfortunate use of “No-Harm Contracts” or “No-Suicide Contracts,” various stabilization planning interventions for suicidal outpatients are intuitively more compelling and have proven effective in clinical trial research. The best known of these interventions is the Safety Plan Intervention (SPI) developed by Drs. Stanley and Brown. Widely adopted in the American Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Department of Defense healthcare systems, the SPI has also been adopted in the public and private sectors as an alternative to coercive contracts that focus on what a patient promises not to do (i.e., kill themselves) versus planning for what they will do within a suicidal, dark moment of crisis. The Safety Plan guides the patient through the steps of identifying triggers, self-coping techniques, distraction by others, reaching out for supportive help, reaching out to professional help, and securing lethal means. The superiority of the SPI over no-harm contracting for reducing suicide attempt behaviors was clearly demonstrated in a large cohort-comparison study of suicidal U.S. military veterans, and additional randomized controlled trial data are now being conducted.

A conceptual “cousin” of the SPI is the “Crisis Response Plan” (CRP), which was first developed by Rudd, Joiner, and Rajab and further elaborated and rigorously studied by Bryan and colleagues. The CRP has the patient note on an index card, in their own written words, various triggers, coping strategies, resources, and oftentimes their reasons for living. Bryan and colleagues conducted a study comparing the CRP to no-harm contracts and showed a significant effect on both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, reducing the latter by 76% at the six-month follow-up assessment.

Another variation on this theme is the CAMS Stabilization Plan (CSP), which is developed in the initial session of the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS). Within this therapeutic framework, the CSP emphasizes securing lethal means, which is followed by a list of coping strategies, resources for outreach, ways for decreasing isolation, and potential barriers to attending CAMS-guided clinical care. The CSP has not been independently studied outside of its use within CAMS, but it is a crucial tool that is routinely used within this evidence-based suicide-focused clinical treatment.

Suicide prevention is a term used for the collective efforts to reduce the incidence of suicide through preventive measures. Protective factors for suicide include support and access to therapy. About 60% of people with suicidal thoughts do not seek help. Reasons for not doing so include low perceived need, and wanting to deal with the problem alone. Despite these high rates, there are effective treatments that focus directly on suicidal thoughts and behaviors and these are proven to reduce suicide attempts in people who need this help. Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), Cognitive therapy for suicide prevention (CT-SP) and Brief Cognitive behavioral therapy BCBT) all focus on practicing, paying attention to and changing thoughts of suicide and suicidal behavior. These are discussed in more detail below.

Some mental health policy advocates are now promoting various peer-support services as part of a compelling alternative to our contemporary current clinical practices within emergency services (refer to: https://crisisnow.com/#core_elements).

There has been little guidance about how to best meet clinical expectations for effective care of suicidal patients. In the United States, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) sponsored a working group to develop affordable and evidence-based approaches to working with suicidal risk across outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department settings. The “Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe” document recommends basic approaches to working with suicidal patients, primarily emphasizing: identification/assessment of risk, stabilization/safety planning, lethal means safety discussions, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (988), and caring contact follow-up (in their now famous RCT, Motto and Bostrom found that sending a simple letter expressing concern and care every four months to patients post-discharge over five years caused a reduction in suicides, when compared to patients who did not receive caring letters).

Effective Clinical Treatments for Suicidal Risk

Dialectical Behavior Therapy

The most notable and heavily researched treatment that has been shown to reduce suicidal behaviors regardless of the intent to die, is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). DBT has four main components: individual therapy, skills training, phone coaching, and a consultation team. DBT’s main goal is to teach the patient skills to regulate emotions and improve relationships with others (suicidality is always targeted at the forefront of care). Skills are taught through validation and acceptance with a genuine focus on behavioral change. DBT was one of the first evidence-based treatments shown to be effective in decreasing repetitive self-harm behaviors and suicide attempts. More recent results have demonstrated DBT’s continued impact on decreasing suicidal behaviors among high risk individuals such as those with borderline personality disorder, and decreasing suicide ideation and self-harm among adolescents. However, while DBT has shown impressive results in managing suicidal behaviors, it is not solely devoted to treating suicidality, and replicated results for reliably decreasing suicidal ideation are not consistent across all DBT RCTs.

Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention

Another effective treatment that targets the “suicidal mode” is Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CT-SP). CT-SP treats the clinical characteristics of suicidal behaviors by using various cognitive therapy techniques, which have proven successful for treating an extensive array of psychiatric disorders. In a well-powered RCT (with a deliberately longer follow-up period than previous RCTs—18 months), Brown and colleagues found that patients in CT-SP treatment were 50% less likely to attempt suicide compared to those in the usual care treatment group. The researchers also found significant reductions in levels of depression and hopelessness in the CT-SP treatment group compared to the control. This study showed high internal validity; replication of the data in a real world setting (e.g., a community-based outpatient setting) with varied samples (e.g., those who have not attempted suicide, but with severe ideation) is a pending next step for the researchers of CT-SP.

Brief Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Brief Cognitive Behavior Therapy (BCBT) was used in one well-powered RCT with suicidal, active duty U. S. Army Soldiers and was shown to be effective for reducing suicide attempts. As its name indicates, this modality is brief (i.e., 12 sessions) to accommodate short-term treatment environments. This variation of CBT suicide-focused care emphasizes: common effective treatment elements, developing skills (e.g., emotion regulation, mindfulness), a focus on the suicidal mode, and the development of self-management. Rudd and colleagues followed soldiers for 24 months and found that compared to treatment as usual, those in the brief CBT group were 60% less likely to attempt suicide.

The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality

Jobes describes the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) as a distinctive therapeutic framework that targets suicidality. As a framework, not a new psychotherapy, the CAMS intervention does not require clinicians to give up their theoretical orientation or abandon reliable techniques. Indeed, CAMS is a “non-denominational” approach where potentially any treatment can be used within the framework. In RCTs comparing CAMS to usual care control conditions there is strong evidence that CAMS significantly reduces suicidal ideation and overall psychiatric distress; it also increases hope and retention to care. In on RCT comparing DBT to CAMS, CAMS did as well as DBT in reducing suicidal attempts and self-harm behaviors. Beyond the initial four published RCTs, five additional CAMS RCTs are in various stages of completion and will add to this growing body of literature.

Profile

How can you spot risk factors of suicide?

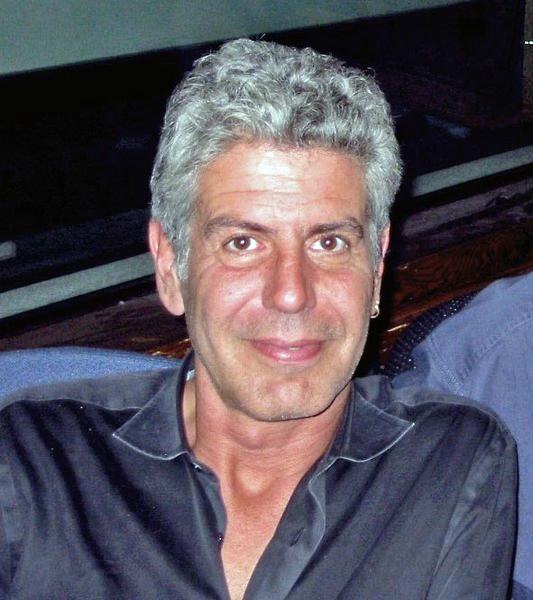

In early June 2018, Anthony Bourdain was working on an episode of Parts Unknown in Strasbourg, with his frequent collaborator and friend Éric Ripert. On June 8, Ripert became worried when Bourdain had missed dinner and breakfast. He subsequently found Bourdain dead of an apparent suicide in his room at Le Chambard hotel in Kaysersberg near Colmar. Bourdain was 61 years old.

Christian de Rocquigny du Fayel, the public prosecutor for Colmar, said Bourdain’s body bore no signs of violence and the suicide appeared to be an impulsive act. Rocquigny du Fayel disclosed that Bourdain’s toxicology results were negative for narcotics, showing only a trace of a therapeutic non-narcotic medication. Bourdain’s body was cremated in France on June 13, 2018, and his ashes were returned to the United States two days later.

Bourdain’s mother, Gladys Bourdain, told The New York Times: “He is absolutely the last person in the world I would have ever dreamed would do something like this.” Following the news of Bourdain’s death, various celebrity chefs and other public figures expressed sentiments of condolence. Among them were fellow chefs Andrew Zimmern and Gordon Ramsay, and former astronaut Scott Kelly. CNN issued a statement, saying that Bourdain’s “talents never ceased to amaze us and we will miss him very much.” Former U.S. President Barack Obama, who dined with Bourdain in Vietnam on an episode of Parts Unknown, wrote on Twitter: “He taught us about food—but more importantly, about its ability to bring us together. To make us a little less afraid of the unknown.” On June 8, 2018, CNN aired Remembering Anthony Bourdain, a tribute program. In the days following Bourdain’s death, fans paid tribute to him outside his now-closed former place of employment, Brasserie Les Halles. Cooks and restaurant owners gathered together and held tribute dinners and memorials and donated net sales to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. In August 2018, CNN announced that it would broadcast a final, posthumous season of Parts Unknown, completing its remaining episodes using narration and additional interviews from featured guests, and two retrospective episodes paying tribute to the series and Bourdain’s legacy. A collection of Bourdain’s personal items were sold at auction in October 2019, raising $1.8 million, part of which is to support the Anthony Bourdain Legacy Scholarship at his alma mater, The Culinary Institute of America. The most expensive item sold was his custom Bob Kramer Steel and Meteorite Chef’s knife, selling at a record $231,250.

Key Takeaways

CAMS Stabilization Plan (CSP)

A plan that emphasizes securing lethal means, which is followed by a list of coping strategies, resources for outreach, ways for decreasing isolation, and potential barriers to attending Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) guided clinical care.

Crisis Response Plan (CRP)

A technique that has the patient note on an index card, in their own written words, various triggers, coping strategies, resources, and oftentimes their reasons for living.

Safety Plan Intervention (SPI)

A plan guides the patient through the steps of identifying triggers, self-coping techniques, distraction by others, reaching out for supportive help, reaching out to professional help, and securing lethal means.

988 is the number of the national Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Suicidal ideation

Thoughts of ending one’s life but not taking any active efforts to do so.

Suicide

Defined by the CDC as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as the result of the behavior”

“Suicide and Prevention” is adapted from Abnormal Psychology by Coursehero, used under CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.