28 Development of Schizophrenia

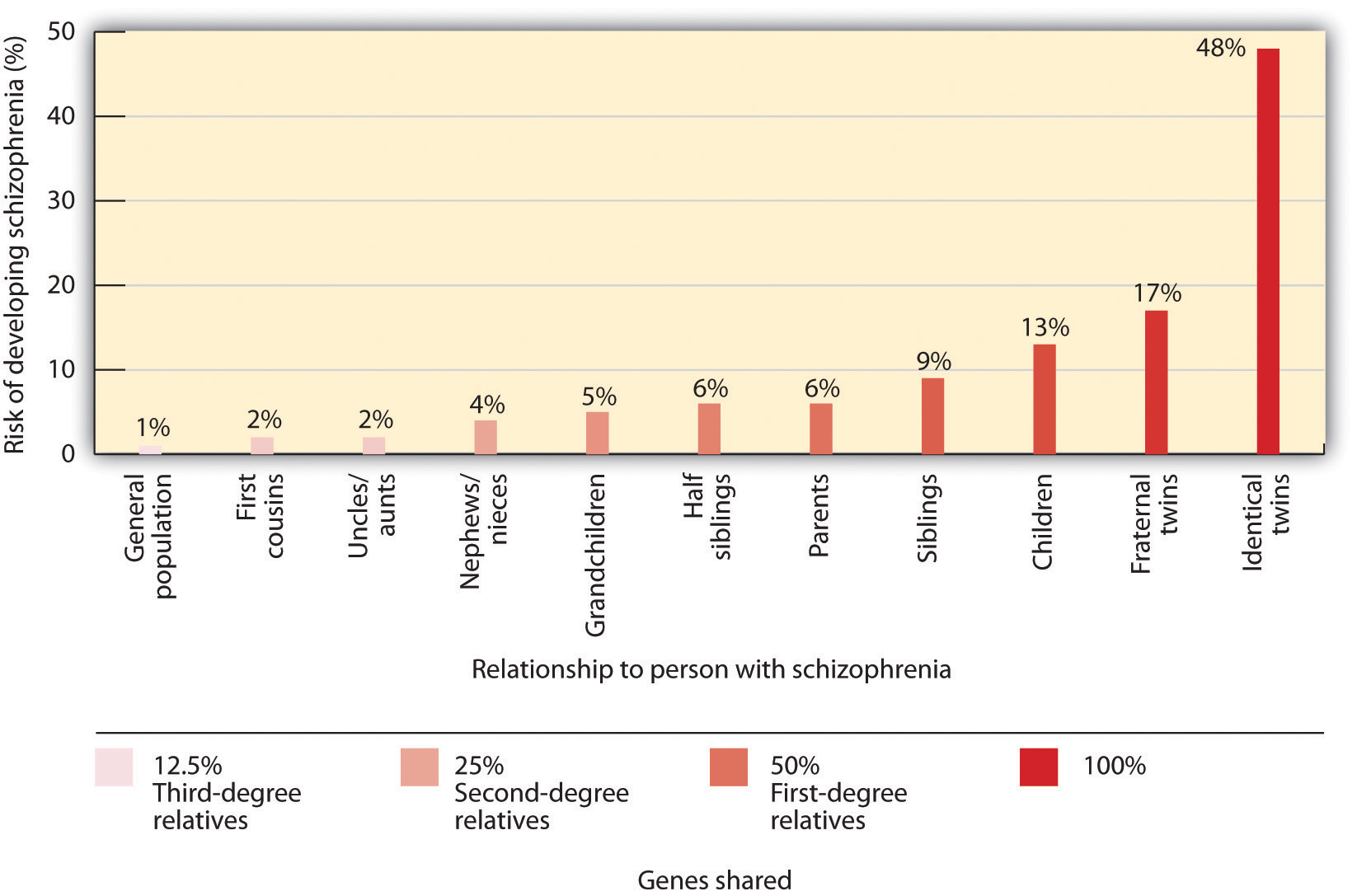

It is clear that there are important genetic contributions to the likelihood that someone will develop schizophrenia, with consistent evidence from family, twin, and adoption studies. (Sullivan, Kendler, & Neale, 2003). However, there is no “schizophrenia gene” and it is likely that the genetic risk for schizophrenia reflects the summation of many different genes that each contribute something to the likelihood of developing psychosis (Gottesman & Shields, 1967; Owen, Craddock, & O’Donovan, 2010). Further, schizophrenia is a very heterogeneous disorder, which means that two different people with “schizophrenia” may each have very different symptoms (e.g., one has hallucinations and delusions, the other has disorganized speech and negative symptoms). This makes it even more challenging to identify specific genes associated with risk for psychosis. Importantly, many studies also now suggest that at least some of the genes potentially associated with schizophrenia are also associated with other mental health conditions, including bipolar disorder, depression, and autism (Gejman, Sanders, & Kendler, 2011; Y. Kim, Zerwas, Trace, & Sullivan, 2011; Owen et al., 2010; Rutter, Kim-Cohen, & Maughan, 2006).

The likelihood of developing schizophrenia increases dramatically if a close relative also has the disease.

There are also a number of environmental factors that are associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia. For example, problems during pregnancy such as increased stress, infection, malnutrition, and/or diabetes have been associated with increased risk of schizophrenia. In addition, complications that occur at the time of birth and which cause hypoxia (lack of oxygen) are also associated with an increased risk for developing schizophrenia (Cannon, Jones, & Murray, 2002; Miller et al., 2011). Children born to older fathers are also at a somewhat increased risk of developing schizophrenia. Further, using cannabis increases risk for developing psychosis, especially if you have other risk factors (Casadio, Fernandes, Murray, & Di Forti, 2011; Luzi, Morrison, Powell, di Forti, & Murray, 2008). The likelihood of developing schizophrenia is also higher for kids who grow up in urban settings (March et al., 2008) and for some minority ethnic groups (Bourque, van der Ven, & Malla, 2011). Both of these factors may reflect higher social and environmental stress in these settings. Unfortunately, none of these risk factors is specific enough to be particularly useful in a clinical setting, and most people with these “risk” factors do not develop schizophrenia. However, together they are beginning to give us clues as the neurodevelopmental factors that may lead someone to be at an increased risk for developing this disease.

An important research area on risk for psychosis has been work with individuals who may be at “clinical high risk.” These are individuals who are showing attenuated (milder) symptoms of psychosis that have developed recently and who are experiencing some distress or disability associated with these symptoms. When people with these types of symptoms are followed over time, about 35% of them develop a psychotic disorder (Cannon et al., 2008), most frequently schizophrenia (Fusar-Poli, McGuire, & Borgwardt, 2012). In order to identify these individuals, a new category of diagnosis, called “Attenuated Psychotic Syndrome,” was added to Section III (the section for disorders in need of further study) of the DSM-5 (APA, 2013).

However, adding this diagnostic category to the DSM-5 created a good deal of controversy (Batstra & Frances, 2012; Fusar-Poli & Yung, 2012). Many scientists and clinicians have been worried that including “risk” states in the DSM-5 would create mental disorders where none exist, that these individuals are often already seeking treatment for other problems, and that it is not clear that we have good treatments to stop these individuals from developing to psychosis. However, the counterarguments have been that there is evidence that individuals with high-risk symptoms develop psychosis at a much higher rate than individuals with other types of psychiatric symptoms, and that the inclusion of Attenuated Psychotic Syndrome in Section III will spur important research that might have clinical benefits. Further, there is some evidence that non-invasive treatments such as omega-3 fatty acids and intensive family intervention may help reduce the development of full-blown psychosis (Preti & Cella, 2010) in people who have high-risk symptoms.

Biological

Genetic/Family studies

Twin and family studies consistently support the biological theory. More specifically, if one identical twin develops schizophrenia, there is a 48 percent chance that the other will also develop the disorder within their lifetime (Coon & Mitter, 2007). This percentage drops to 17 percent in fraternal twins. Similarly, family studies have also found similarities in brain abnormalities among individuals with schizophrenia and their relatives; the more similarities, the higher the likelihood that the family member also developed schizophrenia (Scognamiglio & Houenou, 2014).

Neurobiological

There is consistent and reliable evidence of a neurobiological component in the transmission of schizophrenia. More specifically, neuroimaging studies have found a significant reduction in overall and specific brain regions volumes, as well as tissue density of individuals with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls (Brugger, & Howes, 2017). Additionally, there has been evidence of ventricle enlargement as well as volume reductions in the medial temporal lobe. As you may recall, structures such as the amygdala (involved in emotion regulation), the hippocampus (involved in memory), as well as the neocortical surface of the temporal lobes (processing of auditory information) are all structures within the medial temporal lobe (Kurtz, 2015). Additional studies also indicate a reduction in the orbitofrontal regions of the brain, a part of the frontal lobe that is responsible for response inhibition (Kurtz, 2015).

Dopamine Functioning

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia is a model used by scientists to explain many schizophrenic symptoms. The model claims that a high fluctuation of levels of dopamine can be responsible for schizophrenic symptoms. The simplest version of this theory suggests that schizophrenia is associated with an increase of dopamine in the central nervous system. However, this original dopamine theory has given way to a more nuanced revised dopamine theory.

The revised dopamine theory developed from additional research that has identified two dopamine pathways in particular that are associated with the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The first is the mesolimbic system, which affects areas regulating reward pathways and emotional processes; the second is the mesocortical system, which affects the prefrontal cortex, areas that regulate cognitive processing, and areas involved with motor control. Excess activity in the mesolimbic pathway and lack of activity in the mesocortical pathway are thought to be responsible for positive and negative symptoms, respectively. The dopamine hypothesis has helped progress the development of antipsychotics, which are drugs that stabilize positive symptoms by blocking dopamine receptors. The fact that these medications have been shown to treat psychosis supports the dopamine theory.

Other Neurotransmitters

Dopamine is not the only neurotransmitter associated with schizophrenia, although it can be argued that it is the most studied. Seratonin and glutamate have also been linked with schizophrenia. Increased levels of seratonin are associated with positive symptoms. Glutamate has been theorized to exacerbate hyperactivity and hypoactivity in dopamine pathways, affecting both positive and negative symptoms.

Stress Cascade

The diathesis-stress model suggests that individuals have a genetic or biological predisposition to develop the disorder, however, symptoms will not present unless there is a stressful precipitating factor that elicits the onset of the disorder. Researchers have identified the HPA axis and its consequential neurological effects as the likely responsible neurobiological component responsible for this stress cascade.

The HPA axis is one of the main neurobiological structures that mediates stress. It involves the regulation of three chemical messengers (corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and glucocorticoids) as they respond to a stressful situation (Corcoran et al., 2003). Glucocorticoids, more commonly referred to as cortisol, is the final neurotransmitter released which is responsible for the physiological change that accompanies stress to prepare the body to “fight” or “flight.”

It is hypothesized that in combination with abnormal brain structures, persistent increased levels of glucocorticoids in brain structures may be the key to the onset of psychosis in prodromal patients (Corcoran et al., 2003). More specifically, the stress exposure (and increased glucocorticoids) affects the neurotransmitter system and exacerbates psychotic symptoms due to changes in dopamine activity (Walker & Diforio, 1997). While research continues to explore the relationship between stress and onset of disorder, evidence for the implication of stress and symptom relapse is strong. More specifically, schizophrenia patients experience more stressful life events leading up to a relapse of symptoms. Similarly, it is hypothesized that the worsening or exacerbation of symptoms is also a source of stress as they interfere with daily functioning (Walker & Diforio, 1997). This stress alone may be enough to initiate the onset of a relapse.

Psychological

Cognitive

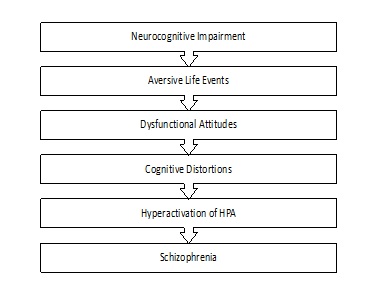

The cognitive model utilizes some of the aspects of the diathesis-stress model in that it proposes that premorbid neurocognitive impairment places individuals at risk for aversive work/academic/interpersonal experiences. These experiences in return lead to dysfunctional beliefs and cognitive appraisals, ultimately leading to maladaptive behaviors such as delusions/hallucinations (Beck & Rector, 2005).

Beck proposed the following diathesis-stress model of development of schizophrenia:

Adapted from Beck & Rector, 2005, pg. 580

Based on this theory, an underlying neurocognitive impairment (as discussed above) makes an individual more vulnerable to experience aversive life events such as homelessness, conflict within the family, etc. Individuals with schizophrenia are more likely to evaluate these aversive life events with a dysfunctional attitude and maladaptive cognitive distortions. The combination of the aversive events and negative interpretations of them, produces a stress response in the individual, thus igniting hyperactivation of the HPA axis. According to Beck and Rector (2005), it is the culmination of these events leads to the development of schizophrenia.

Sociocultural

Expressed emotion

Research in support of a supportive family environment suggests that families high in expressed emotion, meaning families that have high hostile, critical, or overinvolved family members, are predictors of relapse (Bebbington & Kuipers, 2011). In fact, individuals who return to families post hospitalization with high criticism and emotional involvement are twice as likely to relapse compared to those who return to families with low expressed emotion (Corcoran et al., 2003). Several meta-analyses have concluded that family atmosphere are causally related to relapse in patients with schizophrenia, and that these outcomes can be improved when the family environment is improved (Bebbington & Kuipers, 2011). Therefore, one major treatment goal in families of patients with schizophrenia is to reduce expressed emotion within family interactions.

Family dysfunction

Even for families with low levels of expressed emotion, there is often an increase in family stress due to the secondary effects of schizophrenia. Having a family member who was diagnosed with schizophrenia increases the likelihood of a disruptive family environment due to managing the patients symptoms and ensuring their safety while they are home (Friedrich et al., 2015). Because of the severity of symptoms, families with a loved one diagnosed with schizophrenia often report more conflict in the home as well as more difficulty communicating with one another (Kurtz, 2015).

Real stories: Elyn Saks “A tale of mental illness – from the inside”

Elyn Saks is Associate Dean and Orrin B. Evans Professor of Law, Psychology, and Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences at the University of Southern California Gould Law School and an expert in mental health law.

Elyn Saks gave a powerful TED talk in 2012 describing her experiences with schizophrenia and treatment: https://www.ted.com/talks/elyn_saks_a_tale_of_mental_illness_from_the_inside?subtitle=en. To quote her TED bio:

“Is it okay if I totally trash your office?” It’s a question Elyn Saks once asked her doctor, and it wasn’t a joke. A legal scholar, in 2007 Saks came forward with her own story of schizophrenia, controlled by drugs and therapy but ever-present. In this powerful talk, she asks us to see people with mental illness clearly, honestly and compassionately.

As a mental health law scholar and writer, Elyn Saks speaks for the rights of mentally ill people. It’s a gray area: Too often, society’s first impulse is to make decisions on their behalf. But it’s a slippery slope from in loco parentis to a denial of basic human rights. Saks has brilliantly argued for more autonomy — and in many cases for a restoral of basic human dignity.

In 2007, her autobiography, The Center Cannot Hold, revealed the depth of her own schizophrenia, now controlled by drugs and therapy. Clear-eyed and honest about her own condition, the book lent her new ammunition in the quest to protect the rights and dignity of the mentally ill.”

Listen to the Podcast: A candid conversation with Elyn Saks: “In solidarity, with pride, and without shame”.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Diathesis-stress model

Model that suggests that individuals have a genetic or biological predisposition to develop a disorder, however, symptoms will not present unless there is a stressful precipitating factor that elicits the onset of the disorder.

Neurodevelopmental

Processes that influence how the brain develops either in utero or as the child is growing up.

Revised dopamine theory

Theory of schizophrenia development proposing that excess dopamine activity in the mesolimbic pathway and lack of activity in the mesocortical pathway are thought to be responsible for positive and negative symptoms, respectively.

“Development of Schizophrenia” is adapted from Abnormal Psychology by Coursehero, used under CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.