33 What is Personality?

Cristina Crego, Thomas Widiger, Jorden A. Cummings, and Cailey Strauss

Section Learning Objectives

- Define what is meant by a personality disorder.

- Identify the five domains of general personality.

Personality & the Five-Factor Model

Everybody has their own unique personality; that is, their characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others (John, Robins, & Pervin, 2008). Some people are typically introverted, quiet, and withdrawn; whereas others are more extraverted, active, and outgoing. Some individuals are invariably conscientiousness, dutiful, and efficient; whereas others might be characteristically undependable and negligent. Some individuals are consistently anxious, self-conscious, and apprehensive; whereas others are routinely relaxed, self-assured, and unconcerned. Personality traits refer to these characteristic, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. There are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and, basically, what they are like most every day throughout much of their lives.

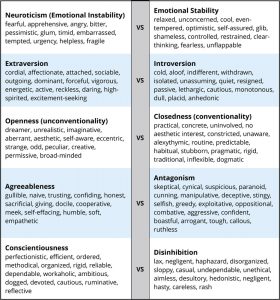

There are literally hundreds of different personality traits. All of these traits can be organized into the broad dimensions referred to as the Five-Factor Model (John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008). These five broad domains are inclusive; there does not appear to be any traits of personality that lie outside of the Five-Factor Model. This even applies to traits that you may use to describe yourself. Table 9.1 provides illustrative traits for both poles of the five domains of this model of personality. A number of the traits that you see in this table may describe you. If you can think of some other traits that describe yourself, you should be able to place them somewhere in this table.

DSM-5 Personality Disorders

When personality traits result in significant distress, social impairment, and/or occupational impairment, they are considered to be a personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The authoritative manual for what constitutes a personality disorder is provided by the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the current version of which is DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The DSM provides a common language and standard criteria for the classification and diagnosis of mental disorders. This manual is used by clinicians, researchers, health insurance companies, and policymakers.

According to the DSM-5, a personality disorder is characterized by a pervasive, consistent, and enduring pattern of behaviour and internal experience that differs significantly from that which is usually expected in the individual’s culture. They typically have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, persist over time, and cause distress or impairment. The pattern must be present in two or more of the four areas of cognition, emotion, interpersonal functioning, and impulse control. It must also not be better explained by another mental disorder or medical condition, or as the effects of a substance. There was much discussion in writing the DSM-5 about changing the way in which personality disorders are diagnosed, but for now the system remains unchanged from the previous version of the DSM (the DSM-IV-TR). DSM-5 includes 10 personality disorders, grouped into three clusters: Cluster A (paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders), Cluster B (antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders), and Cluster C (avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders).

This list of 10 though does not fully cover all of the different ways in which a personality can be maladaptive. DSM-5 also includes a “wastebasket” diagnosis of other specified personality disorder (OSPD) and unspecified personality disorder (UPD). This diagnosis is used when a clinician believes that a patient has a personality disorder but the traits that constitute this disorder are not well covered by one of the 10 existing diagnoses. OSPD and UPD or as they used to be referred to in previous editions – PDNOS (personality disorder not otherwise specified) are often one of the most frequently used diagnoses in clinical practice, suggesting that the current list of 10 is not adequately comprehensive (Widiger & Trull, 2007).

Each of the 10 DSM-5 (and DSM-IV-TR) personality disorders is a constellation of maladaptive personality traits, rather than just one particular personality trait (Lynam & Widiger, 2001). In this regard, personality disorders are “syndromes.” For example, avoidant personality disorder is a pervasive pattern of social inhibition, feelings of inadequacy, and hypersensitivity to negative evaluation (APA, 2013), which is a combination of traits from introversion (e.g., socially withdrawn, passive, and cautious) and neuroticism (e.g., self-consciousness, apprehensiveness, anxiousness, and worrisome). Dependent personality disorder includes submissiveness, clinging behavior, and fears of separation (APA, 2013), for the most part a combination of traits of neuroticism (anxious, uncertain, pessimistic, and helpless) and maladaptive agreeableness (e.g., gullible, guileless, meek, subservient, and self-effacing). Antisocial personality disorder is, for the most part, a combination of traits from antagonism (e.g., dishonest, manipulative, exploitative, callous, and merciless) and low conscientiousness (e.g., irresponsible, immoral, lax, hedonistic, and rash). See the 1967 movie, Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty, for a nice portrayal of someone with antisocial personality disorder.

Some of the DSM-5 personality disorders are confined largely to traits within one of the basic domains of personality. For example, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is largely a disorder of maladaptive conscientiousness, including such traits as workaholism, perfectionism, punctilious, ruminative, and dogged; schizoid is confined largely to traits of introversion (e.g., withdrawn, cold, isolated, placid, and anhedonic); borderline personality disorder is largely a disorder of neuroticism, including such traits as emotionally unstable, vulnerable, overwhelmed, rageful, depressive, and self-destructive (watch the 1987 movie, Fatal Attraction, starring Glenn Close, for a nice portrayal of this personality disorder); and histrionic personality disorder is largely a disorder of maladaptive extraversion, including such traits as attention-seeking, seductiveness, melodramatic emotionality, and strong attachment needs (see the 1951 film adaptation of Tennessee William’s play, Streetcar Named Desire, starring Vivian Leigh, for a nice portrayal of this personality disorder).

It should be noted though that a complete description of each DSM-5 personality disorder would typically include at least some traits from other domains. For example, antisocial personality disorder (or psychopathy) also includes some traits from low neuroticism (e.g., fearlessness and glib charm) and extraversion (e.g., excitement-seeking and assertiveness); borderline includes some traits from antagonism (e.g., manipulative and oppositional) and low conscientiousness (e.g., rash); and histrionic includes some traits from antagonism (e.g., vanity) and low conscientiousness (e.g., impressionistic). Narcissistic personality disorder includes traits from neuroticism (e.g., reactive anger, reactive shame, and need for admiration), extraversion (e.g., exhibitionism and authoritativeness), antagonism (e.g., arrogance, entitlement, and lack of empathy), and conscientiousness (e.g., acclaim-seeking). Schizotypal personality disorder includes traits from neuroticism (e.g., social anxiousness and social discomfort), introversion (e.g., social withdrawal), unconventionality (e.g., odd, eccentric, peculiar, and aberrant ideas), and antagonism (e.g., suspiciousness).

The APA currently conceptualizes personality disorders as qualitatively distinct conditions; distinct from each other and from normal personality functioning. However, included within an appendix to DSM-5 is an alternative view that personality disorders are simply extreme and/or maladaptive variants of normal personality traits, as suggested herein. Nevertheless, many leading personality disorder researchers do not hold this view (e.g., Gunderson, 2010; Hopwood, 2011; Shedler et al., 2010). They suggest that there is something qualitatively unique about persons suffering from a personality disorder, usually understood as a form of pathology in sense of self and interpersonal relatedness that is considered to be distinct from personality traits (APA, 2012; Skodol, 2012). For example, it has been suggested that antisocial personality disorder includes impairments in identity (e.g., egocentrism), self-direction, empathy, and capacity for intimacy, which are said to be different from such traits as arrogance, impulsivity, and callousness (APA, 2012).

Outside Resources

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) https://www.appi.org/products/structured-clinical-interview-for-dsm-5-scid-5

Web: DSM-5 website discussion of personality disorders http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/PersonalityDisorders.aspx

References

Allik, J. (2005). Personality dimensions across cultures. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 212–232.

American Psychiatric Association (2012). Rationale for the proposed changes to the personality disorders classification in DSM-5. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/PersonalityDisorders.aspx.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2001). Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2012). Mentalization-based treatment of borderline personality disorder. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 767–784). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Beck, A. T., Freeman, A., Davis, D., and Associates (1990). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders, (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bornstein, R. F. (2012). Illuminating a neglected clinical issue: Societal costs of interpersonal dependency and dependent personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68, 766–781.

Cailhol, L., Pelletier, E., Rochette, L., Laporte, L., David, P., Villeneuve, E., … & Lesage, A. (2017). Prevalence, mortality, and health care use among patients with Cluster B personality disorders clinical diagnosed in Quebec: A provincial cohort study, 2001-2012. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62, 336-342. doi: 10.1177/0706743717700818

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Crego, C. & Widiger, T. (2020). Personality Disorders. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/67mvg5r2.

DeYoung, C. G., Hirsh, J. B., Shane, M. S., Papademetris, X., Rajeevan, N., & Gray, J. (2010). Testing predictions from personality neuroscience: Brain structure and the Big Five. Psychological Science, 21, 820–828.

Gunderson, J. G. (2010). Commentary on “Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: Toward a more complete integration in DSM-5 and an empirical model of psychopathology.” Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 1, 119–122.

Gunderson, J. G., & Gabbard, G. O. (Eds.), (2000). Psychotherapy for personality disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Hare, R. D., Neumann, C. S., & Widiger, T. A. (2012). Psychopathy. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 478–504). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hooley, J. M., Cole, S. H., & Gironde, S. (2012). Borderline personality disorder. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 409–436). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hopwood, C. J. (2011). Personality traits in the DSM-5. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 398–405.

John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. R. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality. Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

John, O. P., Robins, R. W., & Pervin, L. A. (Eds.), (2008). Handbook of personality. Theory and Research (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Livesley, W. J. (2011). Confusion and incoherence in the classification of personality disorder: Commentary on the preliminary proposals for DSM-5. Psychological Injury and Law, 3, 304–313.

Lynam, D. R., & Widiger, T. A. (2001). Using the five factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 401–412.

Lynch, T. R., & Cuper, P. F. (2012). Dialectical behavior therapy of borderline and other personality disorders. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 785–793). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Miller, J. D., Widiger, T. A., & Campbell, W. K. (2010). Narcissistic personality disorder and the DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 640–649.

Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of personality. Introducing a DSM/ICD spectrum from normal to abnormal (3rd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Mullins-Sweatt; Bernstein; Widiger. Retention or deletion of personality disorder diagnoses for DSM-5: an expert consensus approach. Journal of personality disorders 2012;26(5):689-703.

Perry, J. C., & Bond, M. (2000). Empirical studies of psychotherapy for personality disorders. In J. Gunderson and G. Gabbard (Eds.), Psychotherapy for personality disorders (pp. 1–31). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Roberts, B. W., & DelVecchio, W. F. (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25.

Shedler, J., Beck, A., Fonagy, P., Gabbard, G. O., Gunderson, J. G., Kernberg, O., … Westen, D. (2010). Personality disorders in DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1027–1028.

Skodol, A. (2012). Personality disorders in DSM-5. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 317–344.

Smith, G. G., & Zapolski, T. C. B. (2009). Construct validation of personality measures. In J. N. Butcher (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Personality Assessment (pp. 81–98). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Torgerson, S. (2012). Epidemiology. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 186–205). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Widiger, T. A. (2009). Neuroticism. In M. R. Leary and R.H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 129–146). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Widiger, T. A., & Trull, T. J. (2007). Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist, 62, 71–83.

Yamagata, S., Suzuki, A., Ando, J., One, Y., Kijima, N., Yoshimura, K., … Jang, K. L. (2006). Is the genetic structure of human personality universal? A cross-cultural twin study from North America, Europe, and Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 987–998.

“What Is Personality?” is adapted from Abnormal Psychology by Jordan A. Cummings, used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.